Scarred for Life: Why Women Got Tattooed During the Armenian Genocide

By Luise Glum

Black dots and lines are scattered over L. Bilandjian’s face, marking the tip of her nose, her forehead and cheeks, running down her chin and throat. They appear to be tattoos, but their origin and significance has little in common with the contemporary understanding of tattooing. Bilandjian is a 17-year-old girl from Aintab, now known as Gaziantep. And her tattoos are a record of the horrors she had to endure as a consequence of the Armenian Genocide. A photograph of her tattooed face can be found in the Armenian Genocide Museum in Yerevan, an entire wall is filled with images of women who had to go through similar experiences. Many of the photographs were taken by Karen Jeppe, a Danish missionary who ran a shelter for Armenian women and children in Aleppo.

Gender played a crucial role in the organization of the Armenian Genocide. As genocide researcher Katharine Derderian writes, there was a “definite link between genocidal and gender ideologies”. The genders were separated; the male population was then massacred, while many members of the female population were raped, abused, and taken as slaves or brides. Karen Jeppe stated in 1926 that amongst the thousands of Armenian women and girls she had encountered, all but one had been sexually abused. In addition, many were forced to convert from Christianity to Islam. This separation of the genders was grounded in the assumption that only adult males acted as carriers of “ethnicity”, while women (and children) could be assimilated into non-Armenian society, their cultural values erased and reprogrammed. Assimilation and conversion were important structural components of the genocide and aimed at erasing Armenian identity.1

A huge number of Armenian women and children thus ended up kidnapped, sold, or “voluntarily” living among their captors to escape deportation. In the course of their assimilation, many Armenian women were tattooed in the same way as the members of their new communities. At the time of the genocide, tattooing was a widespread practice in eastern Anatolia and the northern Levant. Kurds, Turks, Arabs, Yazidis, and many other ethnic groups decorated their bodies with tattoos. However, the use of tattoos was not a common custom among Armenians.2

As a result of a large-scale assistance mission after the First World War, many female victims were later “reclaimed” by the Armenian community. They found shelter in rescue homes, which were often established by North American and European missionaries and volunteers. However, not all Armenian women were treated in the same way. The tattoos which some women carried on their faces constituted a barrier to readmission into their home communities.3

Origin and Design of the Tattoos

It is difficult to identify which ethnic groups were responsible for the tattoos. In research literature, their new communities and thus the presumed originators of these tattoos are labelled as Turks, Kurds, Arabs, or Bedouins. In general, scholars seem to concur that all of these new communities followed Islam. The oldest evidence of tattooing in the region dates back to the Mesopotamian city-state of Ur in 4,000 BCE. Figurines found there have black markings on their shoulders, which are interpreted as depicting early tattoos. Although tattooing was and still is controversial in Islam, it was a common practice among rural communities. Yet, as Anthropologist Winifred Smeaton noted in 1937, over the course of the 20th century, it was gradually becoming unpopular. In the area corresponding to present-day Turkey, tattooing was mostly practiced in eastern and southern Anatolia and was usually called daqq or dövün.4

The practice appears to have been very similar in Turkish, Kurdish, and Arab communities. The pigment used for tattooing was made out of diverse ingredients, although the fundamental component was lampblack. The design was painted on the surface of the skin before being poked into the hypoderm using a needle. The tattooists were mainly women, whether professionals, women who tattooed themselves, or mothers who tattooed their children. The chin, neck, chest, ankles, and hands were common places for tattoos.

The tattoos documented in the photographs of the Armenian women are located on their faces, necks, and hands and are dark in color. The tattoos vary in form: in some photographs, they consist of fine dots and delicate lines, while in others they are thick and irregular. The marks are usually arranged symmetrically and are quite small, up to a few centimeters in size.

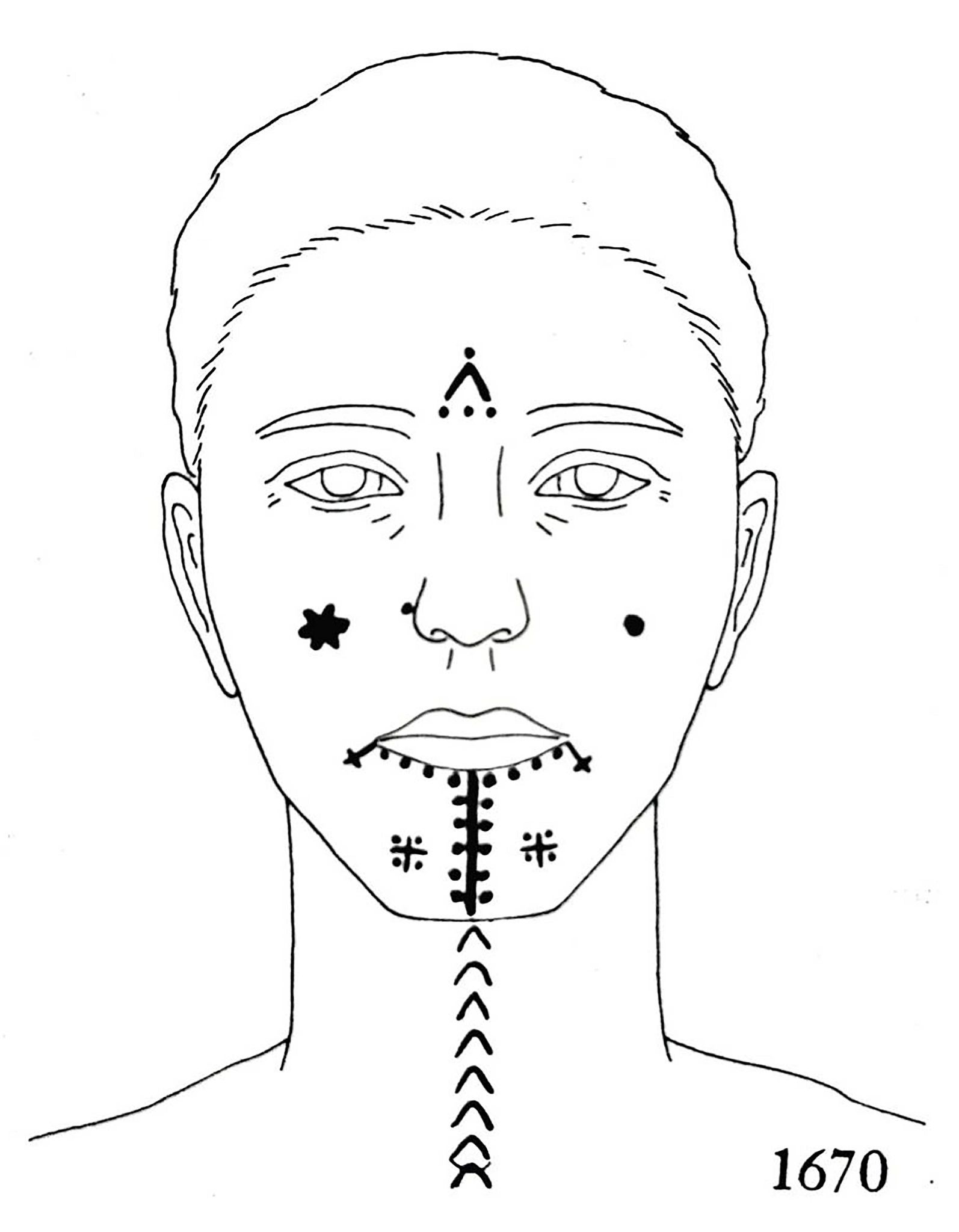

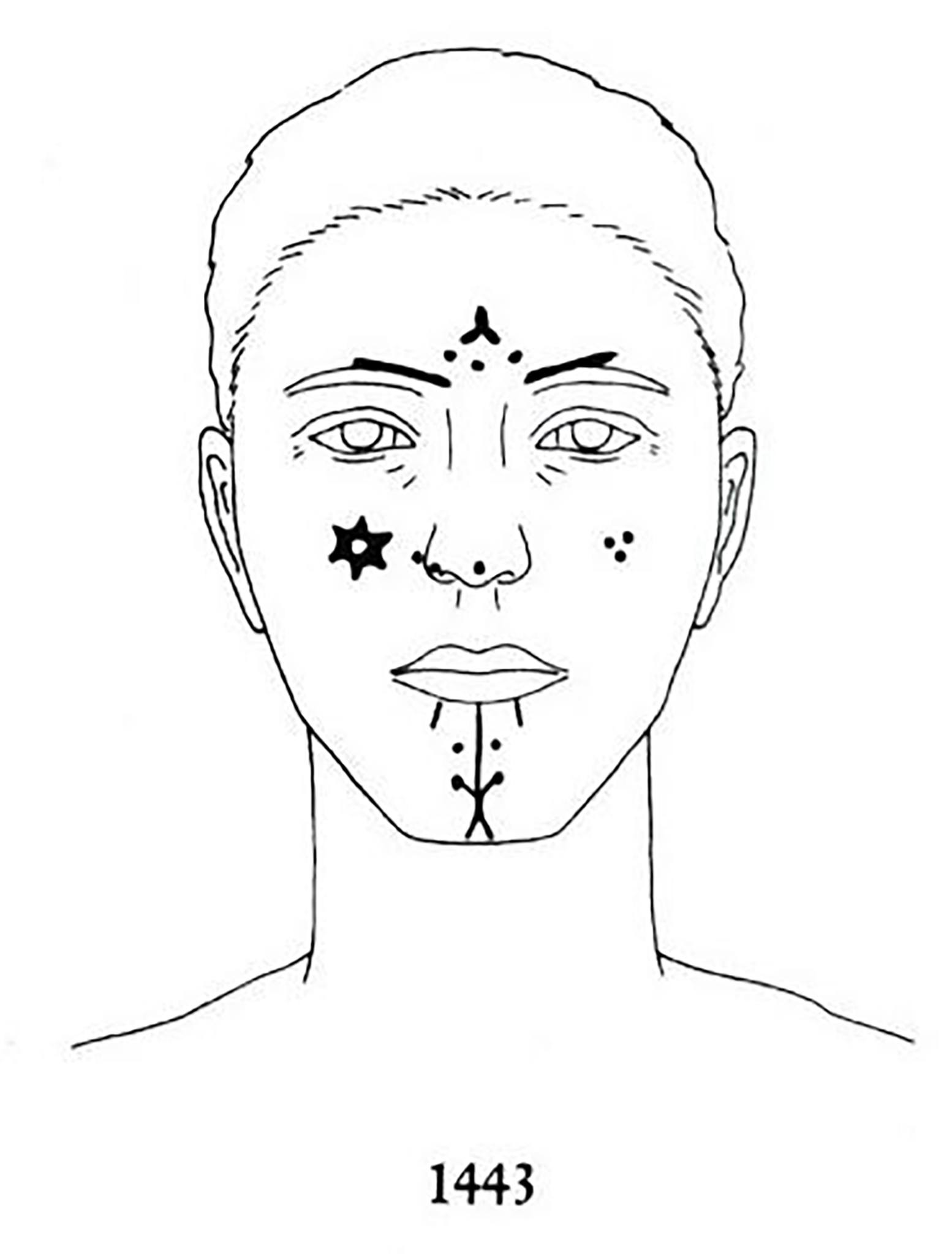

The appearance of those tattoos can be compared with the common practice of tattooing in the region though schematic drawings, that anthropologist Henry Field fabricated during his research. Putting images of the Armenian women and his sketches side by side shows striking similarities. The photograph below shows Astghik, a 16-year-old girl from Urfa. The sketch next to her depicts the tattoos of a Solubba woman, the Solubba were an ethnic group that lived primarily on the Arabian Peninsula and about whom little information is available. Both women display a very similar style of tattooing, a line along the chin and neck, which is called ṣadr and consists of dots and crescents.

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Astghik, 16 years old, from Urfa. (© Nubarian Library collection) |

Fig. 3: Depiction of the tattoos of a Solubba woman. (© Henry Field (1958), figure 5) |

Another example is Mariam Chaparlian, a 27-year-old woman from Marash. Her tattoos show great similarities with the sketch of a Schammar woman. According to Field, the Schammar were “Bedouins”. Both women have three dots tattooed on their cheeks, though on the opposite sides of their faces. The designs on their chins are also very similar: in the center, starting beneath the mouth, is a line with two dots to the left and to the right, terminating in a reverse V.

|

|

|

Fig. 4: Mariam Chaparlian, 27 years old, from Marash. (© Nubarian Library collection) |

Fig. 5: Depiction of the tattoos of a Schammar woman. (© Henry Field (1958), figure 5) |

In the photograph of Armenian woman Jeghsa Hairabedian, her tattooed hand is visible. Sources reveal that her tattooists were Kurds.5 Her marks resemble the hands depicted in image 7: on her wrist, we see an extensive comb, while on the back of her hand, there are arrangements of circles and dots resembling suns. However, the hands depicted in figure 7 belonged to a Yazidi woman, which shows once more the similarities of the markings across ethnic groups.

|

|

|

Fig. 6: Jeghsa Hairabedian, from Adiaman. (© Nubarian Library collection) |

Fig. 7: Depiction of the tattoos of Yazidi women (© Henry Field (1958), figure 4) |

Tattoos as a form of bodily regulation

Two pivotal aspects constitute a tattoo: it originates from an intentional action and is a permanent mark on the skin. Although nowadays methods for removing tattoos exist, they cannot be simply taken off or washed away; they are meant to last a lifetime. Tattoos are carriers of meaning, they convey a message to those who see them. It is therefore essential to consider the context of the tattoo, as well as the relationship between the tattoo, the tattooed person, and the tattooer.6

While tattoos are nowadays mostly viewed as a means of individual self-expression, in the context of the Armenian Genocide, they take on a rather different significance, as a form of regulation. Coerced tattoos are an appropriation of the enemy’s body, an interference in a person’s physicality that is reshaped at the will of another. During this process of regulation difference is visibly established or erased. Tattoos can create social boundaries, document an individual’s position within society and radically transform it.7 In the context of the tattooed women of the Armenian Genocide, the dialectical character of this boundary formation is crucial, since assimilation is simultaneously accompanied by social exclusion: by being assimilated into a new community, exclusion from the old one becomes inevitable.

According to the findings of Anthropologists Field and Smeaton, the common practice of tattooing in the region was rarely connected to coercion. Mostly, women served as tattooists, which highlights the link between this practice and gender. For the Armenian women who were assimilated into non-Armenian communities, however, the tattoo took on the opposite connotations. Alongside other bodily regulations, like rape and captivity, tattoos were a form of deprivation of physical integrity. Tattooing was a means of assimilation along with forced marriages, the imposition of non-Armenian names, and the compulsory learning of a new language. Through the irreversibility of the tattoo, the deprivation of freedom assumed an all-encompassing character. The tattoos embody a continuous actualization of their origin – an act of violence – and preserve the tattooed person’s experiences.8

Ethnographer Verjiné Svazlian collected over 300 Testimonies of genocide survivors, and some of the records provide information about the women's perspectives on their tattoos. Haykoush Miridjan Ohanian describes how the process of being tattooed was connected to violence: “The Arabs held me, put me down on the ground and put a mill-stone on my breast. I was kicking my feet saying: ‘I don’t want’, and they wanted to tattoo my face, to make me look like an Arab girl.” The accounts show that for the women, this regulation was strongly connected to ethnicity. Barouhi Chorekian recounts: “Swimming across the Khabur River (river flowing near Der-Zor), we reached near the Arab Bedouins. They sheared off our lice-infested hair; they tattooed our face with ink in order to hide our Armenian origin.” Not only were the Armenian women brought into alignment with the women in their new communities, but their old identities were supposed to be overwritten. It was the visual level that made the assimilation evident and irreversible.

For those Armenian women who escaped their captors, their tattooed bodies were once again a matter of regulation, both within the women’s refuges and within groups composed of other Armenians. The tattoos symbolized a disgraceful memory and were therefore to be ignored, suppressed, and, in the best case, removed from the skin. Gayané Adourian recounts how her mother tried to remove her tattoos, which led to further injury: “But they used to laugh at me. I did not know Armenian. There were blue tattoos on my face. My poor mother tried to remove them with nitric acid, but it burnt my skin. It corroded my skin and left scars up to this day.” Sirena Aram Alajajian states that because of her tattoos she was unable to find a husband: “During my youth, a very polite Armenian youth met me. He admired my looks and knowledge of languages, but he said that without the blue tattoos on my pretty face, we might have gotten married. So, what the Arabs did with my face was the reason for me to remain all alone in my old age.”

But often it was North Americans and Europeans who prevented the reintegration of the tattooed women into Armenian communities: Historian Jinks states that only Missionary Karen Jeppe accepted all Armenian women into her women’s house without discrimination. The tattooed women rarely appear in the records and fundraising materials, an indicator of the discomfort surrounding tattoos among relief workers. Jinks explains the strong rejection tattoos triggered in terms of the “contemporary cultural unease in Western society regarding tattoos”. Europeans had tattooed convicts in their colonies, often on the face, and tattoos were seen as a sign of a “primitive” civilization. Europeans who were tattooed were often those perceived as living at the margins of society: seafarers, soldiers, and, in the case of women, sex workers.9

Many missionaries and volunteer workers described the tattoos as a type of disfigurement, a stigma, as marks of shame and slavery – what “delineated the rescued women as an outcast group”, as Jinks puts it. This exclusion was closely connected to religious and sexual concerns, since the tattoos were permanent reminders of the women’s relationships with Muslim men: “the image of sexual subjection evoked by the tattoos was intolerable, and also a symbol that the women’s innocence and purity had been corrupted”, writes Jinks. According to the historian, especially among the missionaries, it was widely believed that the Armenian population had been “Islamized”. As their goal was to reconstruct the Armenian nation not only as a political and religious group, the recoverability of the women, especially of the tattooed women, was questionable. “Women, as child-bearers and custodians of domesticity, had to epitomize Armenianness”, writes Jinks, “most rescuers shrank from the women – suspicious also that the tattoos indicated an individual’s transculturation, and thus divided national loyalties.”10

The fate of the tattooed Armenian women was even discussed in the contemporary US-American press, mirroring many of the same concerns. In an article from 1919 that appeared in the Prescott Journal Miner, a Dr. Post of Princeton University is recorded as claiming that the tattoos indicate that a woman had been “an inmate of a harem”. The articles declares: “The victims of the branding and tattooing, in every case, were Christians and their captors thus marked them as Mohammedans”. Similarly, an article in the New York Times from 1919 claims, “In the tents of the Arabs in the Syrian desert, many were bound and forcibly tattooed on the forehead, lips and chin, to mark them as Moslem women.”

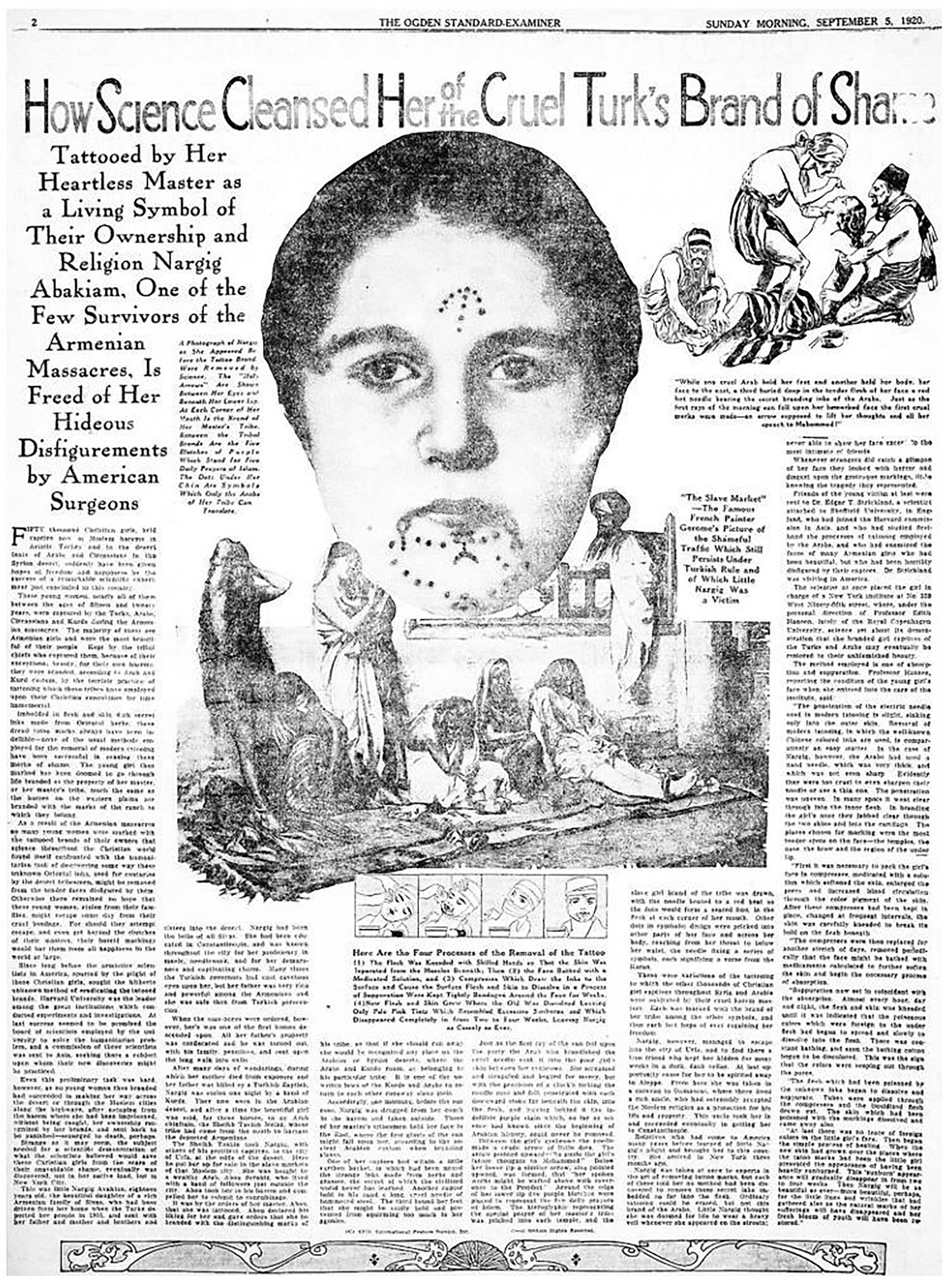

|

|

Fig. 8: “How Science Cleansed Her of the Cruel Turk’s Brand of Shame”, Standard-Examiner, Ogden (Utah), 5 September 1920. (© Utah Digital Newspapers, J. Willard Marriott Digital Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City) |

Figure 8 shows a page from the Standard-Examiner of 1920. It describes the story of Nargig Abakiam, whose tattoos were removed by experts in New York. Their removal was supposed to restore her “beauty”, but at the same time, the language and visualization evidently places the tattoos in a religious and sexual context. In the upper right corner, an imagined scene involving the application of tattoos is drawn. A woman, nearly naked, is being pushed to the ground by three men. The choice of words in the headline is striking: not only has a tattoo been removed, but the woman has been “cleansed” of the “cruel Turk’s brand of shame”. The articles calls the tattoos “Holy Arrows”, “a Living Symbol of Ownership and Religion”, and are described in the following terms:

“Between the girl’s eyebrows the needle made a crude arrow of little dots. The arrow pointed upward – 'to guide the girl’s future thoughts to Mohammed.' Below her lower lip a similar arrow, also pointed upward, was formed, that 'her spoken words might be wafted above with reverence to the Prophet.' Around the edge of her lip five purple blotches were placed to represent the five daily prayers of Islam.”

Having been assimilated into a community they did not want to be a part of and excluded from the community to which they felt they belonged; the tattooed women did not fully belong to any group. After their escape, delineating themselves from the perpetrators of the genocide would have been a logical step toward reinstating their belonging to the Armenian community. Because of their tattooed bodies, the women did not have the chance to realize this demarcation fully. To some degree they were seen as belonging to the group of the perpetrators. The tattoos not only preserved the violence of their origin, they also documented and perpetuated the women’s expulsion.

Bibliography

Akçam, Taner, 2012, The Young Turks’ Crime against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Anderson, Clare, 2000, Godna: Inscribing Indian Convicts in the Nineteenth Century, in: Caplan, Jane (ed.), Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 102–117.

Aumüller, Jutta, 2009, Assimilation: Kontroversen um ein migrationspolitisches Konzept, Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

Betts, Alison, 1989, The Solubba: Nonpastoral Nomads in Arabia, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 274, 61–69.

Birkalan-Gedik, Hande A. 2006, Body: Female: Turkey, Central Asia, and the Caucasus, in: Suad, Joseph (ed.), Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures, vol. 3: Family, Body, Sexu- ality and Health, Leiden: Brill, https://referenceworks-brillonline-com.emedien.ub.uni- muenchen.de/entries/encyclopedia-of-women-and-islamic-cultures/body-female-tur- key-central-asia-and-the-caucasus-EWICCOM_0159g [accessed 13 January 2021].

Bjørnlund, Matthias, 2009, “A Fate Worse than Dying”: Sexual Violence during the Arme- nian Genocide, in: Herzog, Dagmar (ed.), Brutality and Desire: Genders and Sexualities in History, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 16–58.

Çağlayandereli, Mustafa / Göker, Hediye, 2016, Anatolia Tattoo Art; Tunceli Example, Jour- nal of Human Sciences 13, 2, 2545–2562.

Caplan, Jane, 2000, Introduction, in: Caplan, Jane (ed.), Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, xi-xxiii.

Chatty, Dawn / Young, William, 2014, entry “Bedouin”, eHRAF World Cultures, https:// ehrafworldcultures-yale-edu.emedien.ub.uni-muenchen.de/ehrafe/BrowseCultures. do?owc=MJ04#owc [accessed 7 January 2021].

Dahinden, Janine / Duemmler, Kerstin / Moret, Joëlle, 2011, Die Herstellung sozialer Dif- ferenz unter der Bedingung von Transnationalisierung: Religion, Islam und boundary work unter Jugendlichen, in: Allenbach, Birgit / Goel, Urmila / Hummrich, Merle / Weissköppel, Cordula (eds.), Jugend, Migration, Religion: Interdisziplinäre Perspektiven, Zürich: Pano Verlag, 225–248.

Derderian, Katharine, 2005, Common Fate, Different Experience: Gender-Specific Aspects of the Armenian Genocide, 1915–1917, Holocaust and Genocide Studies 19, 1, 1–25. Douglas, Mary, 1966, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo, New

York: Routledge. Eriksen, Thomas H., 2019, The Epistemological Status of the Concept of Ethnicity, Anthro-

pological Notebooks 25, 1, 27–36. Field, Henry, 1958, Body-Marking in Southwestern Asia, Cambridge: The Peabody Mu-

seum. Grigo, Jacqueline, 2015, Religiöse Kleidung: Vestimentäre Praxis zwischen Identität und Dif-

ferenz, Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

Gustafson, W. Mark, 1997, Inscripta in Fronte: Penal Tattooing in Late Antiquity, Classical Antiquity 16, 1, 79–105.

Hainzl, Manfred / Pinkl, Petra, 2003, Lebensspuren hautnah: Eine Kulturgeschichte der Tätowierung, Linz: trod.ART Verlag.

Häusle-Paulmichl, Gunhild, 2018, Der tätowierte Leib: Einschreibungen in menschliche Kör- per zwischen Identitätssehnsucht, Therapie und Kunst, Wiesbaden: Springer.

Jinks, Rebecca, 2018, Marks Hard to Erase: The Troubled Reclamation of “Absorbed” Ar- menian Women, 1919–1927, American Historical Review 123, 1, 86–123.

MacQuarrie, Charles W., 2000, Insular Celtic Tattooing: History, Myth and Metaphor, in: Caplan, Jane (ed.), Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 32–45.

Martin, Chris W., 2019, The Social Semiotics of Tattoos: Skin and Self, London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Oettermann, Stephan, 2000, On Display: Tattooed Entertainers in America and Germany, in: Caplan, Jane (ed.), Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 193–211.

Okkenhaug, Inger M., 2015, Religion, Relief and Humanitarian Work among Armenian Women Refugees in Mandatory Syria, 1927–1934, Scandinavian Journal of History 40, 3, 432–454.

Smeaton, Winifred, 1937, Tattooing among the Arabs of Iraq, American Anthropologist 39, 1, 53–61.

Svazlian, Verjiné, 2011, The Armenian Genocide: Testimonies of the Eyewitness Survivors, Yerevan: Gitoutyoun Publishing House of NASRA.

Thompson, Beverly Y., 2015, Covered in Ink: Tattoos, Women and the Politics of the Body, New York: New York University Press.

Üngör, Uğur Ü., 2012, Orphans, Converts, and Prostitutes: Social Consequences of War and Persecution in the Ottoman Empire, 1914–1923, War in History 19, 2, 173–192. Velliquette Anne, M. / Murray, Jeff, B., 1998, The Tattoo Renaissance: An Ethnographic

Account of Symbolic Consumer Behavior, Advances in Consumer Research 25, 461–467. Zwicky, Regula, 2013, Religion hautnah: Tatauierungen als Medien gezeigt am Beispiel des Reiseberichts von Sir Joseph Banks, in: Glavac, Monika / Höpflinger, Anna-Katharina / Pezzoli-Olgiati, Daria (eds.), Second Skin: Körper, Kleidung, Religion, Göttingen: Vanden-

hoeck & Ruprecht, 79–91. Zwicky, Regula, 2014, Religion Skin-Deep: A Study of the Tattooed Bodies of European

Seafarers, in: Ornella, Alexander D. / Knauss, Stefanie / Höpflinger, Anna-Katharina (eds.), Commun(icat)ing Bodies: Body as a Medium in Religious Symbol Systems, Zürich: Pano Verlag, 257–277.

Top photo: LTR: L. Bilandjian, 17 years old, from Aintab; Astghik, 16 years old, from Urfa; Mariam Chaparlian, 27 years old, from Marash; Jeghsa Hairabedian, from Adiaman © Nubarian Library collection

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment