Pictures

Torbjørn Rødland: Into The Light

There are the situations we find ourselves in, and then there are the situations Torbjørn Rødland puts us in.

Fall 2018 Travis DiehlThere are the situations we find ourselves in, and then there are the situations Torbjørn Rødland puts us in. The Norwegian, Los Angeles-based photographer describes his process as being "like casting and directing a movie. Different actors will give you a different reaction to the same piece of direction,” he says, "and you do need them to give form and physicality to something vague and abstract.” But in these photographs "the difference is—there’s no script, no plot, no story.” Here, in the pliable romanticism of LA’s magic hour, under a blustering, set-flat version of Scandinavia’s thin sun, his images captivate the beautiful people.

Rødland's recent work might be summed up as variations on "two things touching”—a young, red-haired woman and an old, gray-haired one hug among some ferns; two youthful men, on either side of a chain-link fence, hold hands, as if each is the other’s reflection—prompting direct comparisons between model and model, and between model and prop. There is a separation of the image’s content and its maker’s comments on the medium, evinced in Rødland’s work as much by the cold tension of his subjects as by the blown-out flashes and visible edges of backdrops. This is where Rødland departs from his influences, such as Stan Douglas’s homages to cinema and expositions of its artifice, or Cindy Sherman’s self-referential register. With Rødland’s pictures, there is no neat choice between these two paths. There is an aberrant quality sometimes described as lecherous, perverted, or perverse. It would be too easy to say that Rødland’s scenes of a little blond boy in a pet cage, for instance, or of a man’s head squashed by a sneakered foot—or any of his many images of people forced into intimacy, both pinioned and connected at the same time—constitute a moral test.

In another recent photograph, Sophie (2017), an ambiguous model poses belly down on a hardwood floor in front of what appears to be an art-shipping crate. It’s not the tripe-like top or gaudy floral skirt that’s off here, but the stilettos—which are much too small and perched on the heels of the model’s feet.

The picture engages in some old-fashioned gender-bending, in a mode as dry as the dust on the gallery floor. Rødland’s human subjects exude a deadness, a bagginess, even a clownishness that deflate any implied eroticism. "An object is like a person unconscious,” he says. "If I cannot help partly objectifying people I photograph, then I also cannot help looking for life and inferiority in objects.” Indeed, in one backlit, exterior shot, two young men pose with a motorcycle; one with his hand on the other’s shoulder, and the other with a hand on the handlebars. It’s difficult to say if the models sigh over the bike, or if the bike wears the models. Whatever is uncannily joined in this setup follows from Rødland’s craftsman-like insistence that all his effects be produced in camera. If his pictures are perfectly imperfect, it’s because we are too.

Travis Diehl is a writer based in Los Angeles.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

WordsJohn Divola & Mark Ruwedel

Fall 2018 By Amanda Maddox -

Words

WordsIlene Segalove’s Modern America

Fall 2018 By Charlotte Cotton -

Words

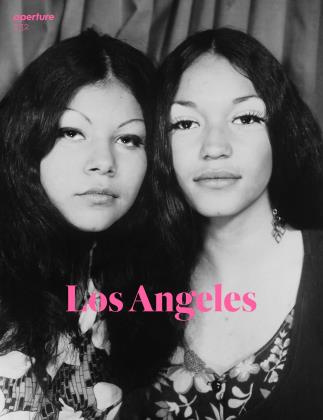

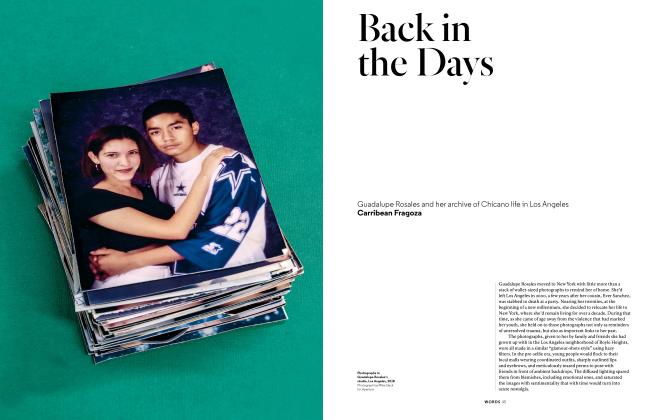

WordsBack In The Days

Fall 2018 By Carribean Fragoza -

Pictures

PicturesPaul Mpagi Sepuya

Fall 2018 By Andy Campbell -

Pictures

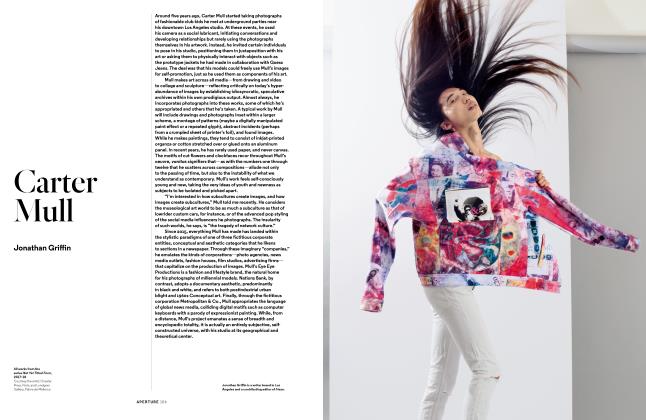

PicturesCarter Mull

Fall 2018 By Jonathan Griffin -

Pictures

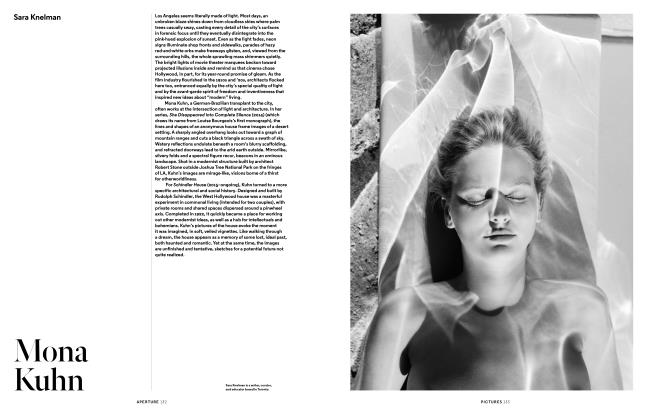

PicturesMona Kuhn

Fall 2018 By Sara Knelman

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Places

-

Words

WordsJohn Divola & Mark Ruwedel

Fall 2018 By Amanda Maddox -

Pictures

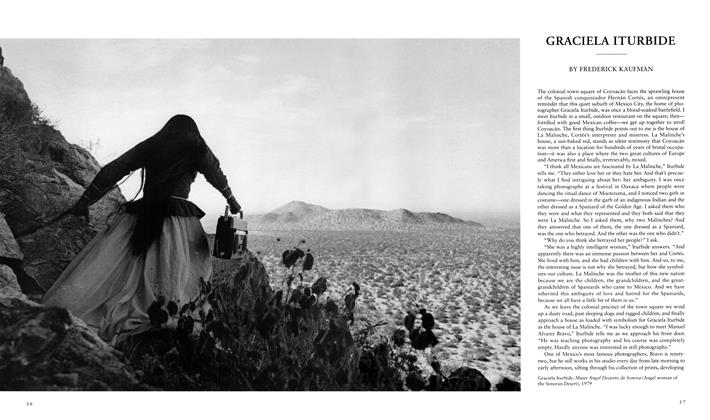

PicturesGraciela Iturbide

Winter 1995 By Frederick Kaufman -

Words

WordsThe Shadow And The Flash

Fall 2019 By Iñaki Bonillas -

Words

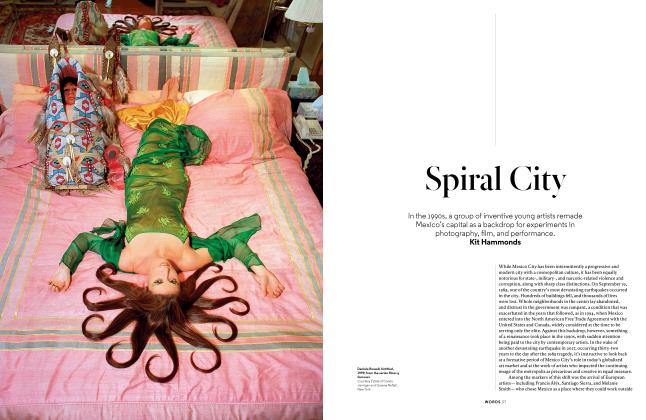

WordsSpiral City

Fall 2019 By Kit Hammonds -

Pictures

PicturesRinko Kawauchi

Summer 2015 By Lesley A. Martin -

Words

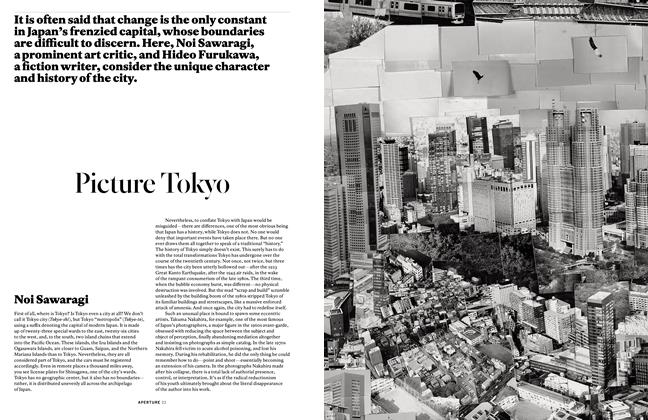

WordsPicture Tokyo

Summer 2015 By Noi Sawaragi, Hideo Furukawa

Pictures

-

Pictures

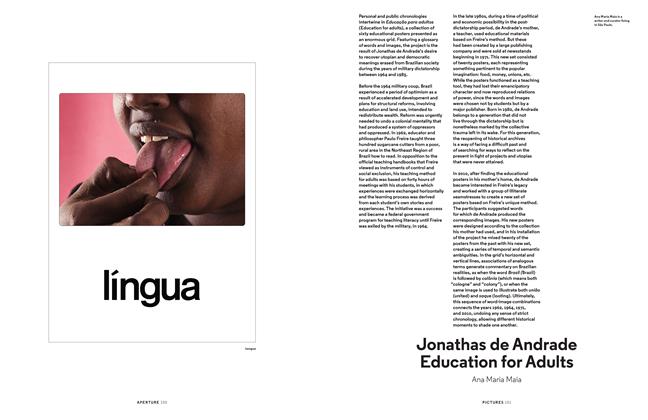

PicturesJonathas De Andrade Education For Adults

Summer 2014 By Ana Maria Maia -

Pictures

PicturesAdam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin

Spring 2013 By Brian Dillon -

Pictures

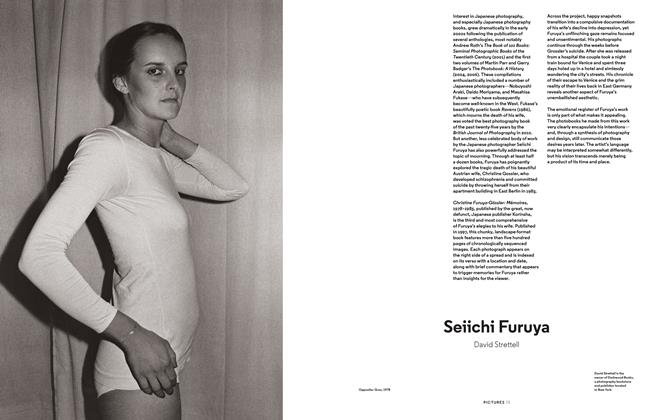

PicturesSeiichi Furuya

Winter 2013 By David Strettell -

Pictures

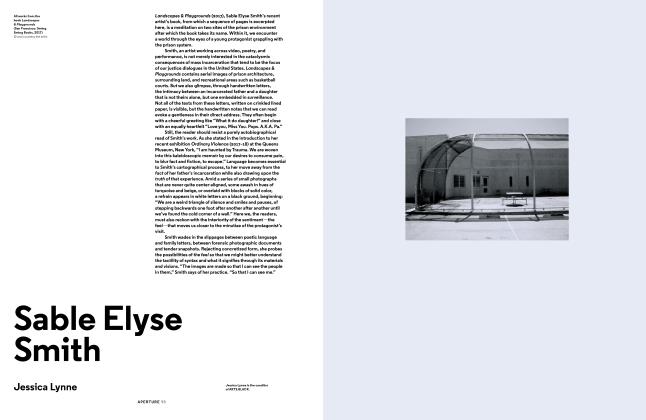

PicturesSable Elyse Smith

Spring 2018 By Jessica Lynne -

Pictures

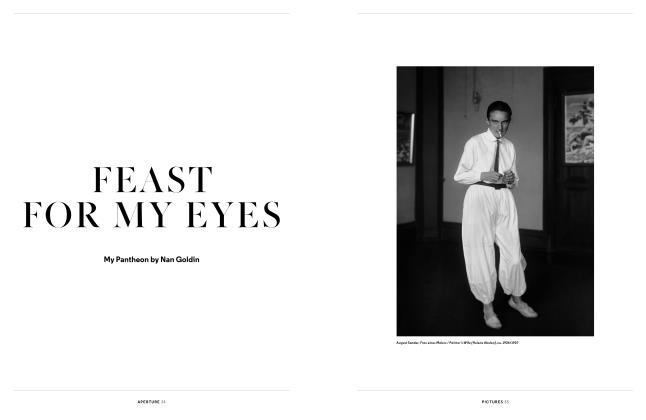

PicturesFeast For My Eyes

Summer 2020 By Nan Goldin -

Pictures

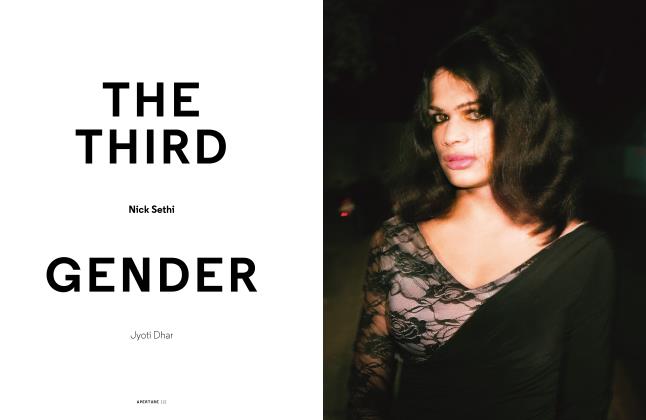

PicturesThe Third Gender

Winter 2017 By Nick Sethi, Jyoti Dhar