When it comes to Norwegian painting, most of us will remember Edvard Munch (1863-1944)—the man behind the iconic Scream. Some time back I discovered Nikolai Astrup, another renowned and beloved artist of the country. He distinguished himself as a painter and printer and is, above all, known for his wild and lush landscapes and depictions of traditional life in Vestlandet (western Norway). Like J.C. Dahl nearly one hundred years earlier, Astrup helped shape the way we view Vestlandet and, in fact, the whole country.

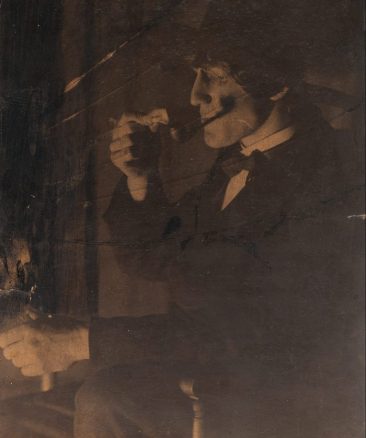

Nikolai Astrup was born in Bremanger, Nordfjord in 1880. His family moved shortly thereafter to Ålhus in Jølster, where his father was a priest. His relationship with his father was marked at times by opposition and conflict, most likely because Nikolai could not quite accept the strict form of Christianity practiced at home. In addition, his wish to become an artist went against his family’s expectations.

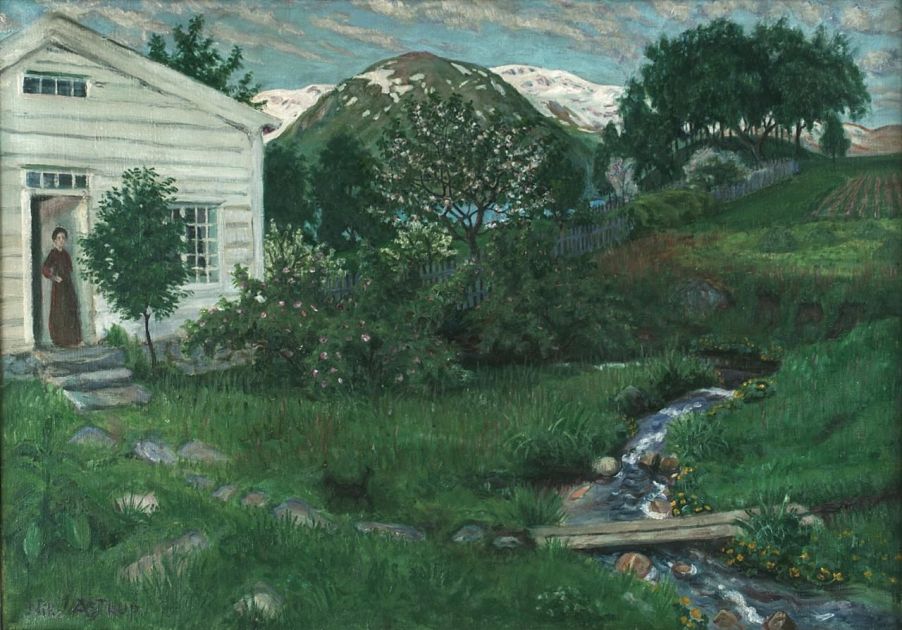

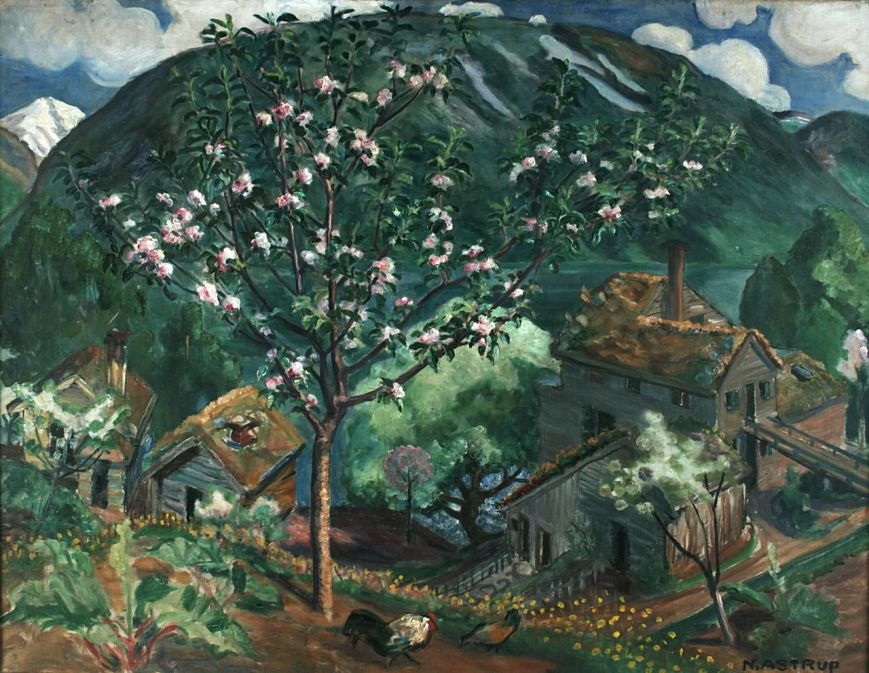

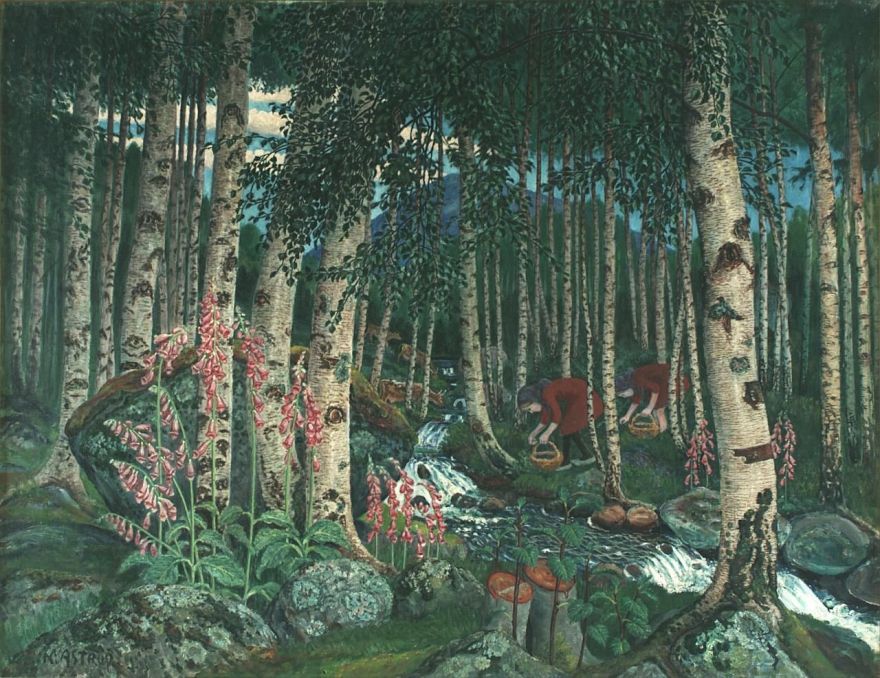

As an artist and bohemian, he stood out in the conventional rural village where he grew up, but he remained in Jølster for most of his life, and it was here that he found the motifs for nearly all of his paintings. Throughout his entire artistic career he focussed on the same landscapes and locations and peopled them with the same human types. He imbued the landscapes with mysticism and an enigmatic symbolic content.

Astrup’s paintings can be seen as a serial treatment of the seasons, given how he depicts the constant and enduring aspects of existence; the little garden with fruit trees and the small vegetable patch, the lake, the familiar mountains, the forest and the fields. These he depicts under constantly changing atmospheric conditions—a drizzling fall morning, a spring thaw, a cold winter day or a mild and soothing summer night.

Apart from his stay in Paris with Krohg, Astrup also travelled to Berlin, Dresden and Hamburg, where he visited the museums in order to study older and contemporary art. He was especially interested in the French primitive painter Henri Rousseau and the Swiss symbolist Arnold Böcklin—the latter fascinated him to such an extent that he later named one of his sons ‘Arnold Böklin Astrup’. In 1902 Astrup moved back to Jølster for good, and a few years later he married Engel, a young peasant girl from the district. Together they had eight children. In addition to his duties on the farm and his obligations towards his family, Astrup continued to develop his art. But it was not easy; the family had little money and Astrup suffered from bad health. He managed, nevertheless, to become one of Norway’s leading artists in the first decades of the 20th century. His woodcuts in particular have earned him a central position in the history of Norwegian art. Along with Edvard Munch, Astrup is considered a pioneer of this printing technique. Nikolai Astrup died of pneumonia in 1928, only 47 years old.

Links: Website (nikolai-astrup.no/en) | Facebook (www.facebook.com/nikolaiastrup)

Thanks to Tove Kårstad Haugsbø of the Kode Art Museums, Bergen for this post.

![]()