Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Bernini in Action

A revelatory show and a new book of historical detection help us take a fresh perspective on an old master.

The Galleria Borghese is the museum that grew out of Scipione Borghese’s big, flashy villa on the hill called the Pincio, overlooking Rome. Scipione, a cardinal and a rapacious art collector, was one of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s most enthusiastic early patrons, and people who walk into the his former residence today and see Bernini’s life-size marble sculpture of Pluto abducting Proserpina circle around it in astonishment, delighted by how real it looks from every angle, trying to decide what the best viewpoint might be. A kindred form of spatial perplexity assails visitors to some of Bernini’s architectural creations, like his baldaquin, or fixed canopy, under the dome of Saint Peter’s, whose curves intersect kinetically with the pre-existing dome and arches as you draw near, or his late church of Sant’Andrea al Quirinale, erected on an oval plan, whose shape seems to shift spectacularly as you wander around inside it.

Bernini, who lived from 1598 to 1680, worked for six popes, and was regarded from his early youth as a new Michelangelo, was aware, like the other creators of the Italian Baroque, that the world is perceived over lengths of time by moving spectators. One is reminded of Galileo’s patient explanation, about a decade after the completion of Bernini’s Rape of Proserpina, as to why planets like Venus and Mars appear to make zigzags in the heavens: it’s because we see them from an ever-altered perspective, from a revolving earth. Yet the ambulatory or roving approach to Bernini has annoyed some distinguished Bernini experts, such as Rudolf Wittkower and Howard Hibberd, who have strenuously argued that we ought to settle down and stand still. They noted long ago that wherever the master’s sculptures may happen to be placed today, and often they are placed in the middle of large rooms, he himself liked to set them with their backs to the wall, so as to favor one particular sightline. It’s a fascinating issue, involving many aspects of the Baroque sensibility, and I’ll return to it farther along. There’s no question, however, but that Bernini in his studio practice had an acute sense of the passage of time, as exemplified in his drawings and clay sketches, called bozzetti or modelli, which were seldom more than 18 inches tall and were created as roughs or models for full-scale projects. The semblance of movement was his aim with these sketches, and speed of execution allowed him to catch it. He stayed loyal to what he could create within a limited time-frame, which was sometimes only one working session.

Bernini’s clay sketches, about 40 of which are on view at the Metropolitan Museum, in New York, until January 6, and at the Kimbell Museum, in Fort Worth, from February 3 to April 14, remain simply the best, the most exciting, ever made. The show is the first of this sort organized in any country, and is based on many loans from American and European collections, with no fewer than four curators taking part in its organization. In addition to the clay sketches or terracotta models, thirty drawings, including one fine early self-portrait and a remarkable marble piece executed by Bernini together with his father, Pietro, also a sculptor, are on display.

When you make an initial sketch, Bernini would explain to his followers, “always preserve that idea, even in the most elaborately worked things.” The sketches embody a vivid memory of rhythmic freedom won against time constraints, as in recorded blues riffs or jazz improvisations, and the master’s finished works may seem all the richer in retrospect after you’ve examined these gesticulating, almost living hunks of baked earth. Take that marble pair of Pluto and Proserpina, for instance, which is, hands down, the sexiest piece of art ever made: it represents the god of the underworld bearing aloft a wholly naked, undulant, and struggling Proserpina, his fingers pressed deeply into her resilient young flesh with a realism so lifelike and complex that the very calculation of the steps necessary to realize the effect, not to mention its execution, seems impossible. Yet seen in the light of Bernini’s clay sketches the male hand clutching the female thigh becomes less an illustration of an Ovidian myth than an emblem of the artist’s hand molding pliant material, a pretext to extol the magic of art.

Essential to Bernini’s aesthetic is the courage to overstate. Anatomical features are exaggerated and often squared-off, with the upshot that they look more accurate, more charged with the pulse of life, than they would have had the artist exercised restraint. Here he skirts the pitfall into which Benvenuto Cellini, his chief predecessor in the technique of modeling, unguardedly fell. Unlike Bernini, Cellini did not draw rapidly or with genuine bravura, and when he enlarged his famous sculpture of Perseus from a lively wax model he also lost its sense of upward springing and cast a bronze that was static and presentational, a monument to a dictator’s triumph over the Florentine Republic. By contrast, all Bernini’s work, both the sketches and the finished pieces, is instinct with continuous energy, an energy whipped up as often as not by his almost frantic deployment of drapery. Already in the sketches drapery is not significantly subject to gravity, does not express an imaginary billowing wind in any consistent way, does not hook and drift in traditional folds. Rather, being hand-fashioned out of sheets of clay, it is so vagrant and rippling and, in a way, so organic, so tripe-like in consistency, forming reverse curves or S-shaped ridges where the fabric is superfluous or verges upon monotony, that it defies rational perception in the sense that you could never draw it in detail – or, if you did, it would take all day. In the end, because of the sheer quantity of clay representing winding, floating, or twisted fabric, whose texture is too stiff to be readily identified as, say, wool or muslin or silk, Bernini’s terracottas, which can seem painterly in their activation of the space around them, are also anti-pictorial, self-enwrapped, like elaborate nautical knots or the nests of weaver birds.

Bernini did not use armatures to support his clay sketches from the inside, but “wedged” his material – a standard sculptor’s and ceramist’s kneading process that eliminates air pockets – into pillar shapes. These he might buttress at the rear, if in fact there was a pre-determined rear, with further masses of unformed clay, in the interests of stability. To conjure forth a working modello he would then add rolls, sheets, strips of clay, and, if necessary, interior props, using both tools and hands, by pinching, cutting, smoothing, and by sticking on knobs and gobbets, till a draped figure emerged. Some pieces were hollowed out to ward off cracking, others truncated and reassembled, and some terracottas were even given elaborate chromatic patinas.

Perhaps the most winning effect of this show is the presentation at what you might call “craft scale” – the scale of what fits between two hands – of a vision that has always (and correctly) been deemed highly rhetorical. Those tendencies in Italian art that strive toward anatomical hypertrophy, ramped-up gesticulation, lurid slickness, and ecclesiastical narcissism, so fully indulged in Bernini, we see suddenly reduced to almost miniature size. The modern preference for what Bernard Berenson called the “non-eloquent” – the kind of art that doesn’t leave you feeling, as Bernini so often does, that you just can’t work up the expected emotional response – finds some moderate accommodation here. Also accommodated is your natural desire to circle around these small pieces to get an intimate sense of how they were conceived.

Of course we may wonder what our friends Wittkower and Hibberd (who are no longer alive) would make of this restless impulse. “It is one of the strange and ineradicable misapprehensions,” Wittkower wrote, “… that Baroque sculpture presents many points of view. The contrary is the case, and nobody made this clearer than … Bernini himself … for though [such sculptures] stimulate the beholder to circulate, they require the correct viewpoint … to grasp fully the meaning of the action or theme represented.” According to this argument, then, there would be a primary vantage point and a number of “subordinate” vantage points (Hibberd’s word) from which to experience a Bernini sculpture, but examining anything from the rear would surely be verboten.

Since an assembly of clay sketches offers a privileged look at the birth of many of Bernini’s ideas, the Kimbell show represents a prime opportunity to reconsider this claim, which we might call the “correct-viewpoint” argument. And our conclusion, I think, should be that it is neither right nor wrong, but rather that its presuppositions require closer scrutiny. It should be said that among the terracottas at the Kimbell quite a few simply afford no view from the rear: the back is hollowed-out or buttressed by clumps of clay. Others are pieces designed for niches, as the Longinus was for a niche at the transept of Saint Peter’s. Yet others, like the large, highly-finished Moor, a sketch for the Fountain of the Four Rivers, in Piazza Navona, works perfectly when seen from any angle. As far as viewpoints go, much, in addition, depends on lighting, and on position. You could choose to display and light a piece in a way that would have enraged Bernini, but that doesn’t mean that Bernini was right, for there were aspects of the Baroque style that fell outside the peripheral vision even of those who invented it: artistic creation, as we know, is partly a kind of dream, and an artist’s waking directives as to how to perceive his work must be received with a skeptical smile. Hibberd wrote that what Bernini most disliked was a kind of restless, “unrequited” meandering, a “gyration” around a sculpture in search of the true moment of focus, and for all that this language deliciously evokes the erotic appeal of so many Bernini pieces, nothing in reality pins us to a final vantage-point. A lot depends on the viewer’s own religion or culture. Often there is one prime vantage-point for grasping the piece’s devotional message and quite another for grasping Bernini’s limber figurative style at its freest and most expressive. The celebrated Ecstasy of Saint Theresa, in S. Maria della Vittoria, in Rome, is enshrined within an elaborate aedicule of the master’s own devising, featuring subsidiary sculpture and theatrical architecture, but who’s to say that it is not best seen from close-up, where these distractions may be bravely ignored? For a believing Catholic (like Bernini himself) the “true” focus may be one thing, for an art-history fan another, for a devotee of the religion of modern art yet another, and for the literary chap in tweeds with Ovid or an annotated Bible in his pocket it may be something else altogether. The contemporary beholder, it should be added, may be receptive to elliptical storytelling, and hence foreshortened perspectives, in a way that would have puzzled the seventeenth-century viewer. Ultimately, if you try to sketch Bernini sculptures you will find that in many cases a variety of angles do yield viable drawings.

Some sage of Bernini explication – I think it was Rudolf Wittkower again – once said that he had a habit of deriving his sculptures from some classical norm and then, out of sheer exuberance, willfully flouting that norm. An example, copiously illustrated in this show, was his late project for the Angels of the Ponte Sant’Angelo, sculptures commissioned by Pope Clement IX Rospigliosi to decorate the bridge spanning the Tiber below the Castel Sant’Angelo. For these 10 angels, spaced along the ancient bridge at intervals and each bearing an Instrument of the Passion, such as the Crown of Thorns, the Scourge of the Flagellation, and so forth, Bernini knocked out more clay sketches than he had for any previous project, and the bozzetto became his chief means of trying out ideas for this heavenly host. In the end, he himself carved only two in marble, which were eventually replaced by excellent copies – the originals, ironically, are safeguarded in the nave of S. Andrea delle Fratte, a church completed by his arch-rival, Borromini – but even the other eight, beautifully executed by his assistants Giulio Cartari and Paolo Naldini, follow his clay sketches in broad outline.

The lovely, swinging chorus-lines of terracotta angels in this exhibition shows us the mature Bernini at his freest and most relaxed. They also shows us a single classic visual idea getting progressively contorted out of recognition. The idea, as announced in the clay sketches of the Angel with the Crown of Thorns and the Angel with the Superscription (that is, the sign over the Cross proclaiming Jesus as the King of the Jews), couldn’t be simpler: it’s the well-known contrapposto pose, in which one leg bears more weight than the other so that the upper body turns in compensatory equipoise. All the other angels ring changes on the above-mentioned pair, but the variation is accomplished largely through the swagging of drapery, and frankly it’s as if a window dresser had gone mad at midnight with a bolt of material and a passel of mannequins. Here we can see Bernini’s manic energy with imaginary yard-goods reaching its zenith. Starting with the good clean fun of the contrapposto pose, he manages somehow to swirl a devilishly creased and twisted length of fabric between the legs of the androgynous Superscription angel, one of whose shapely gams is coincidentally bared to the upper thigh. (Cover thyself! one can almost hear oneself saying, as if these earthen figurines had ears to hear.) And so it goes with the rest of the seraphic gang, who have knots of vestment clutching at their waists or pennant-like cloth-remnants of a wholly mysterious utility (beyond that of merely rounding out the composition) floating on the fictive whirlwinds about them. In this way drapery, which more than anything cinches Bernini’s originality as a modeler, totally forfeits its traditional, comparatively innocent, function of mantling the body in an emblem of divine grace and becomes instead a passionate, even a somewhat ferocious, quest.

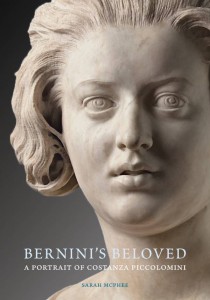

Two recently-published books by accomplished researchers and writers contribute to our sense of how extravagantly impossible Bernini was as a man. Franco Mormando’s charmingly disenchanted Bernini: His Life and his Rome (2011) will leave you even more appalled by the viciousness of the Baroque-era papal court than you probably were to begin with, and fully informed as to the great man’s monumental self-worship, which alarmed even his mother. His most famous egotistical act, of course, was to order a servant to slash the face of his girlfriend Costanza Bonarelli when he had discovered her more or less in flagrante with his brother, Luigi, a math guy who served as the engineering brains of the Bernini firm. (The firm employed so many brilliant people that today the attribution of terracottas can be difficult, and as time went on Bernini was quite content to allow his assistants to realize marble enlargements on the basis of his models.) Till now, for virtually all of us, Costanza has never been anybody but the very pretty, slightly overweight subject (cheekbones were an absolute deal-breaker in Baroque Italy, no girl with cheekbones could hope to find a mate) of the sublime bust by Bernini, perhaps the greatest marble portrait ever carved, that bears her name. This year, however, Sarah McPhee, in her Bernini’s Beloved: A Portrait of Costanza Piccolomini, has unearthed a mine of information about this actually quite enterprising woman, who was, in fact, a scion of a great Sienese family and the wife of an able sculptor in his own right. McPhee’s book is essentially a venture into the history of women in seventeenth-century Rome, but she does offer a few art-critical insights, the chief one being that if you look at the head of Costanza from the rear (it’s in the Bargello, in Florence) you get a very different—less sensual, more poised, more patrician—sense of her identity. In fact, you get a sense of her not so different from what McPhee herself has discovered.

Two recently-published books by accomplished researchers and writers contribute to our sense of how extravagantly impossible Bernini was as a man. Franco Mormando’s charmingly disenchanted Bernini: His Life and his Rome (2011) will leave you even more appalled by the viciousness of the Baroque-era papal court than you probably were to begin with, and fully informed as to the great man’s monumental self-worship, which alarmed even his mother. His most famous egotistical act, of course, was to order a servant to slash the face of his girlfriend Costanza Bonarelli when he had discovered her more or less in flagrante with his brother, Luigi, a math guy who served as the engineering brains of the Bernini firm. (The firm employed so many brilliant people that today the attribution of terracottas can be difficult, and as time went on Bernini was quite content to allow his assistants to realize marble enlargements on the basis of his models.) Till now, for virtually all of us, Costanza has never been anybody but the very pretty, slightly overweight subject (cheekbones were an absolute deal-breaker in Baroque Italy, no girl with cheekbones could hope to find a mate) of the sublime bust by Bernini, perhaps the greatest marble portrait ever carved, that bears her name. This year, however, Sarah McPhee, in her Bernini’s Beloved: A Portrait of Costanza Piccolomini, has unearthed a mine of information about this actually quite enterprising woman, who was, in fact, a scion of a great Sienese family and the wife of an able sculptor in his own right. McPhee’s book is essentially a venture into the history of women in seventeenth-century Rome, but she does offer a few art-critical insights, the chief one being that if you look at the head of Costanza from the rear (it’s in the Bargello, in Florence) you get a very different—less sensual, more poised, more patrician—sense of her identity. In fact, you get a sense of her not so different from what McPhee herself has discovered.

This article originally appeared in the February 2013 issue of Art & Antiques Magazine as “Bernini in Action”

By Dan Hofstadter