From Babylon To Berlin

The Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum

By DR. Adhid Miri, PhD

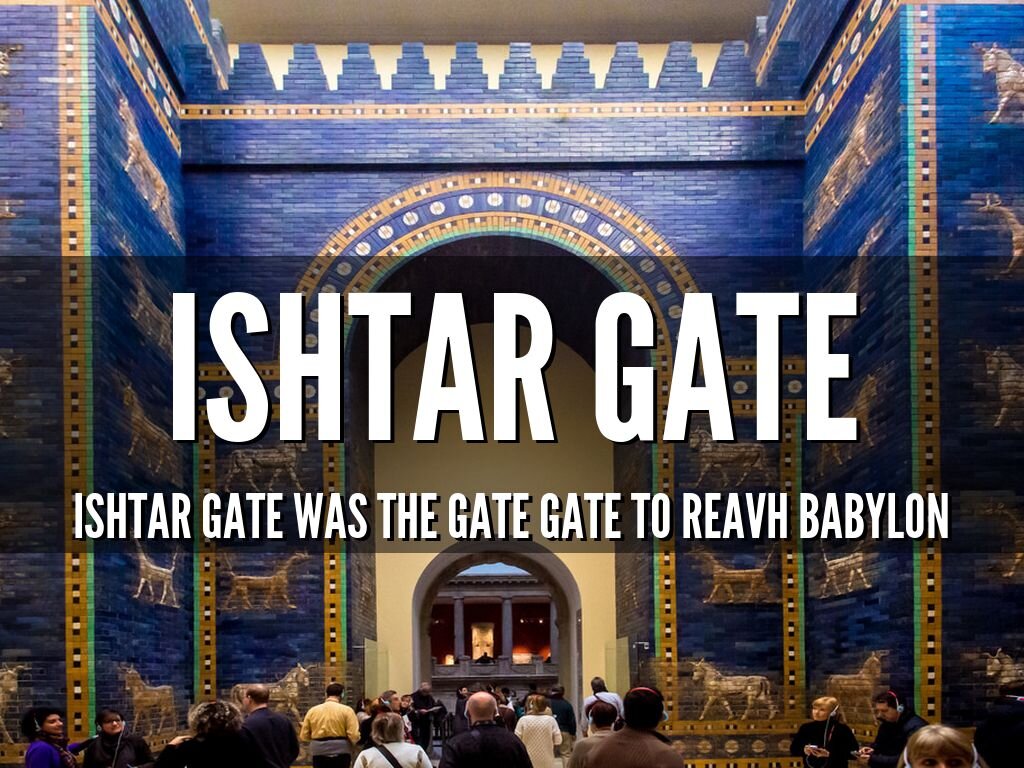

Berlin’s Pergamon Museum is known for its striking reconstructions of large architectural features. One of these, perhaps the most obvious, relates to how the Museum acquired its name - the Pergamon Altar from the ancient city of the Pergamene Kingdom in modern-day Turkey. Another imposing reconstruction is the Ishtar Gate from Babylon, the ancient Mesopotamian city in what is today Iraq.

Located between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, 80 kilometers south of Baghdad and straddling Iraq’s Euphrates river, Babylon was made magnificent by King Nebuchadnezzar II in the 6th Century BC. He made it one of the wonders of Mesopotamia by building large structures and by decorating the structures with expensive glazed bricks in vibrant blues, reds, and yellows. Ancient texts describe the many splendors of Babylon, which at its time was the most significant metropolis in the world.

Since that time, its legend has generated many stories. The Hanging Gardens, the Tower of Babel, and various biblical interpretations added to the mystery of the city. With Babylon’s Ishtar Gate, we can go beyond the legends and experience the art and architecture of the most vibrant and prosperous era of the city. It was so impressive a structure that even in ancient times it was considered a wonder.

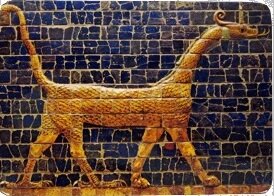

The great Ishtar Gate stood at the entrance to Babylon and has inspired awe since the 6th Century BC. It was the eighth gate of the city of Babylon (in present day Iraq) and was the main entrance into the city. It is thought to have been built around 575 BC, during the reign of King Nebuchadnezzar II. Dedicated to the Babylonian goddess Ishtar, (hence its name), the gate was constructed using glazed brick with alternating rows of bas-reliefs of dragons and bulls, symbolizing the gods Marduk and Adad. It was decorated with lapis lazuli, a deep-blue semi-precious stone, which was used to produce vibrant blue colors. These blue glazed bricks provide the jewel-like shine.

As part of the city walls of Babylon, the Ishtar Gate was one of the original Seven Wonders of the World. The king also restored the temple of Marduk and built the other renowned wonder, the Hanging Gardens, as part of this plan.

Glorious to behold, the gate is one of the most well-documented and ornate sites of early civilization. It was the most important of the eight entry gates into the city of Babylon. The gate was part of a complex system consisting of walls and other defenses, keeping Babylon safe from outside intruders. Additionally, the gate and its adjoining processional way were highly ornamented and illustrate the advanced construction techniques of the ancient Babylonians.

While the Ishtar Gate dates from a time generally referred to as the Neo-Babylonian period (i.e. not the earliest development of Babylon), it does illustrate many of the characteristics of the world’s earliest civilizations. An area known as the fertile crescent; the Euphrates runs directly through the ancient city of Babylon.

Archeology at Babylon has yielded extensive evidence of the city’s development. Many of the characteristics of a civilization are clearly represented at Babylon, including the development of a cuneiform written language (which formed the inscriptions of the Ishtar Gate), a governmental hierarchy (which was responsible for the construction of the Ishtar Gate), an organized religious system (in which Ishtar was one of the most highly regarded deities) and highly developed art and architecture which is illustrated by the Ishtar Gate itself and the sculptural reliefs ornamenting it.

The Ishtar Gate was a part of the building campaigns of King Nebuchadnezzar, who ruled Babylon from 604 to 561 BCE. Nebuchadnezzer’s father, Nabopolassar, had freed Babylon from the control of outsiders and secured the city from invasion. Under Nebuchadnezzer, the city continued to prosper and remained secure due to a complex system of walls, gates and moats.

Interestingly, like most Babylonian remains, much of the gate’s original kiln-fired exterior brick surface has been removed by centuries of vandals, leaving only the softer, inner core of sunbaked bricks.

King Nachbuchanezzar II was one of the most influential and transformative kings of Mesopotamia. It was his vision to create a central powerful cosmopolitan city. He beautified the city with building projects and art, focusing on intellectual pursuits and enlarging the army and territory. His inscription on the Ishtar Gate reads:

“I (Nebuchadnezzar) laid the foundation of the gates down to the ground water level and had them built out of pure blue stone. I covered their roofs by laying majestic cedars lengthwise over them. I hung doors of cedar adorned with bronze at all the gate openings. I placed wild bulls and ferocious dragons in the gateways and thus adorned them with luxurious splendor that people might gaze on them in wonder.”

Nebuchadnezzar pays homage to other Babylonian deities through various animal representations. The animals represented on the gate are young bulls (aurochs), lions, and dragons (sirrush). These animals are symbolic representations of certain deities: lions are often associated with Ishtar, bulls with Adad, and dragons with Marduk. Respectively, Ishtar was a goddess of fertility, love, war, and sex, Adad was a weather god, and Marduk was the chief or national god of Babylon.

When Antipater of Sidon, the Greek poet of the 2nd Century BC, compiled the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, only one city claimed two sites - Babylon. Yet the two he listed – the Hanging Gardens and the Ishtar Gate – were just a couple of the many wonders to be found in the magnificent ancient city.

Babylon, the 4,000-year-old Mesopotamian city once renowned for its Hanging Gardens and opulent temples, has been through a lot in recent decades. Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein played with this ancient citadel by constructing an ostentatious palace on top of its ruins. While Saddam was overthrown by the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, Babylon continued to suffer the wears and tears of modern mistreatment.

During the occupation, for example, American and Polish soldiers set up base there complete with helipad and earth-shuddering military vehicles. It has even had to contend with the indignity of oil and gas pipelines as other forms of modernity have sought to bury the ghosts of its glorious past.

Today, however, this seat of the ancient world is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Its application for inclusion on the illustrious list finally found success after 36 years of lobbying by the Iraqi authorities.

In 1899, the German archaeologist Robert Koldewey began excavating at the city of Babylon. The Ishtar Gate was excavated between 1902 to 1914 CE, during which 45 feet (13.7 m) of the original foundation of the gate was discovered. The material excavated by Koldewey was used in a reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate in 1930, using the original bricks. On display at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, it is widely regarded as one of the most spectacular reconstructions in the history of archaeology.

Due to size restrictions at the museum, the replica is neither complete nor its original size. Originally a double gate, the Pergamon Museum only utilizes the smaller, frontal part. (The second gate is currently in storage.) The gate also had a door and roof made of cedar and bronze, which was not built for the reconstruction. A smaller reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate was built in Iraq under Saddam Hussein as the entrance to a museum. However, this reconstruction was never finished due to war.

There are several museums in the world that have received portions of the Ishtar Gate: the Istanbul Archaeology Museum, the Royal Ontario Museum, the Louvre, Munich’s State Museum of Egyptian Art, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Oriental Institute of Chicago, and even the Detroit Institute of Art, among others.

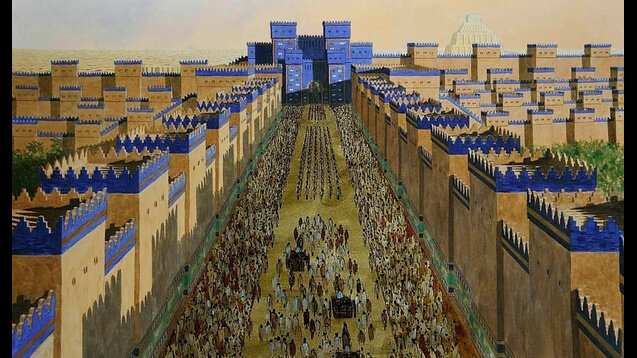

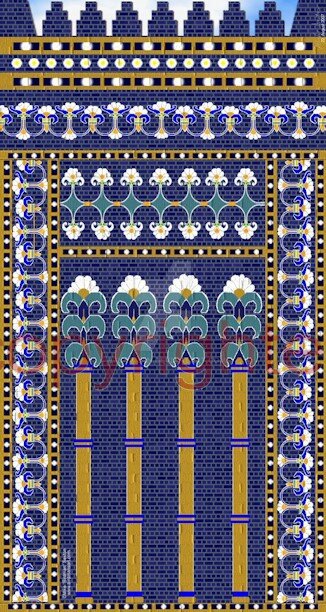

The Ishtar Gate is only one small part of the design of ancient Babylon that also included the palace, temples, an inner fortress, walls, gardens, other gates, and the Processional Way, a red and yellow brick-paved corridor which was initially over half a mile long with walls on each side over 15 meters tall. The walls were constructed of small baked bricks cemented together with bitumen. It was so wide that is said that two chariots meeting on it could safely pass each other. The walls were decorated with over 120 images of lions, bulls, dragons, and flowers, made from enameled blue, yellow, and brown tiles. It led to the temple of Marduk, which was in the form of a ziggurat. Several pieces from the Processional Way were sold and can be seen in museums around the world.

Babylonian craftsmen had advanced knowledge of chemistry, the physical principles of surface chemistry, the science of color fixation, dye properties, high-temperature glazing techniques and engineering furnaces that generated heat temperatures exceeding 5,000 degrees centigrade. They also had connection to other civilizations in the continent as far as Afghanistan to obtain material that was not indigenous to their desert geology.

Symbolic of all that splendor was a visitor’s first introduction to the city vibrant colors. The cobalt blue color of the Ishtar Gate was a Babylonian signature color. It was the color of the skies, the water, and hence the color of the gods.

Alexander the Great, the Macedonian King who conquered the mighty Persian Empire and took over Mesopotamia, could not believe his eyes when approaching Babylon and witnessing the amazing reflections of the deep blue glazed buildings under the desert sun. Blue was a rare natural color in the Mesopotamian world and the glazed bricks must have been a very striking appearance, bringing to life the inscription: “I placed wild bulls and ferocious dragons in the gateways and thus adorned them with luxurious splendor so that people might gaze on them in wonder.”