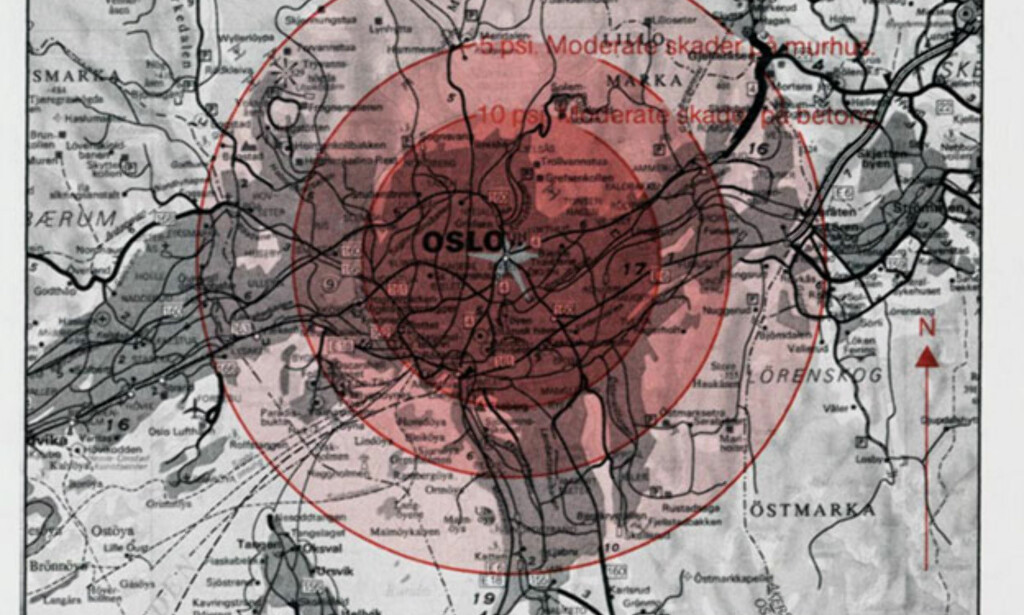

In 1980, a doctor and a researcher in the field of aerodynamics tried to find out what would happen if a nuclear bomb was dropped on Oslo. They envisioned the bomb detonating two kilometres above Sinsen on a clear summer’s day with a breeze from the southwest.

They did not need to specify who they imagined the sender of the bomb to be. This was in the middle of the Cold War, when everything dangerous originated in Moscow.

In the book Atomvåpen og usikkerhetspolitikk (Nuclear Weapons and the Politics of Uncertainty), they state: ‘We are assuming there would be no advance warning since this would be highly irregular.’

A fireball measuring 1000 metres in diameter would form within a second. Then the shockwave would hit the ground, crushing houses and buildings into kindling. The heat radiation would melt glass, metal, animals and people.

When the tremors had subsided, those still alive would see the archetypal mushroom cloud rise up over the capital city. In the days that followed, the Oslo area would be given up for lost, a smoking ruin of ashes and death. Any organised relief work would be abandoned.

‘Only a few desperate individuals intent on finding their loved ones would venture into that radioactive wasteland,’ the two researchers wrote.

During the Cold War, nuclear strikes were a very real fear for many Norwegians. Books were published with survival tips and advice on how to explain the nuclear threat to children.

In the event of a nuclear strike, most people would be hard pressed just to take care of themselves. Many Norwegians – soldiers, firefighters and health professionals – were nevertheless expected to risk their own lives to save as many people as possible.

But there were also some people whose hands would be tied by entirely different plans if war were to break out between the East and the West.

One of these people was a young man, a newly qualified doctor from Poland, who moved into room 724 by the old Rikshospitalet on Langes gate in Oslo in June 1984.

Before any attack on Norway, he would provide information to the intelligence service in his home country on preparedness and how the hospital planned to treat radiation injuries. When the war was underway, he would start working as a radiotelegraph operator.

This young doctor was a foreign spy. An invisible soldier, perfectly integrated into Norwegian society.

«It would be advisable for you to find someone to marry among those whose acquaintance you make, since only marriage to a Norwegian citizen or a woman resident in Norway will allow you to move abroad legally.»

Now, just as back then, he looks fairly unassuming. If you were to walk past him in the street in Oslo, he would look just like any other Norwegian.

He is a well-liked GP and gynaecologist. Every day he drives to his surgery in a low brick building in Oslo. He is one of us. Well and truly settled in a detached house in a suburban area outside the city where he has raised his two Norwegian children. He is known for being a GP who listens, who takes the time to talk to children, who is considerate.

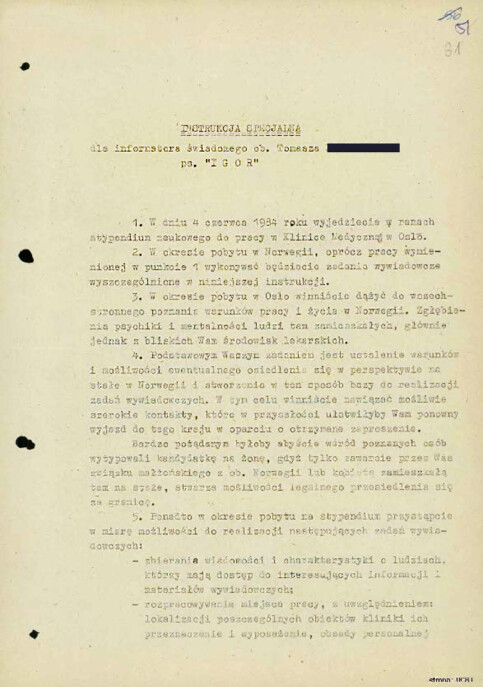

On 1 June 1984, in Lublin in Poland, he signed two sheets of paper – special instructions prior to his trip to Norway.

‘Your primary assignment is to familiarise yourself with the conditions for becoming resident in Norway and in this manner lay a foundation for intelligence assignments,’ the instructions said, continuing:

‘It would be advisable for you to find someone to marry among those whose acquaintance you make, since only marriage to a Norwegian citizen or a woman resident in Norway will allow you to move abroad legally.’

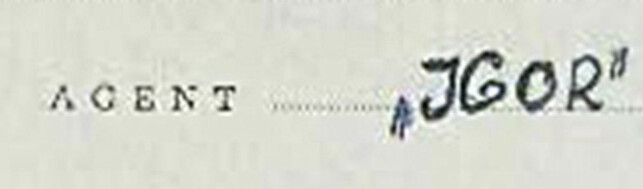

Just below this, the man has signed to confirm that he has read and understood the assignment. The man’s new military identity is given at the top of the instructions. The codename “Igor”.

Although the cold winds from the east stopped blowing long ago, there are still secrets that are yet to be revealed. The Norwegian authorities still restrict access to parts of their archives from the Cold War. Dagbladet has therefore sought out the other primary source: those who were the enemy, engaged to spy on Norway.

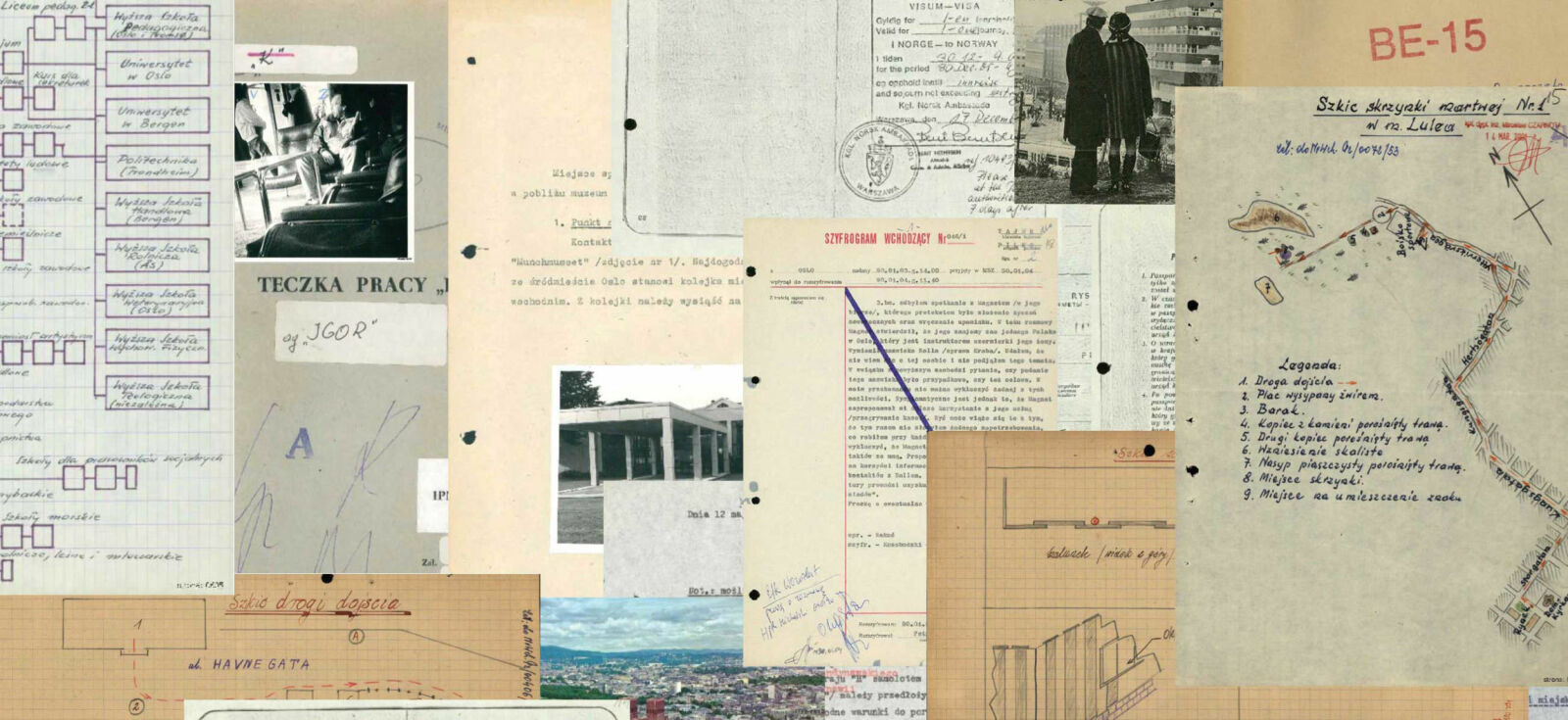

With help from history professor Przemyslaw Gasztold at the Polish Institute of National Remembrance (IPN), Dagbladet has gained access to thousands of formerly confidential documents about Polish operations in Norway from 1960 to 1991. The documents are so-called “declassified” and have been released by the Polish government.

The files contain intelligence reports, personnel files, maps, secret invasion plans, codenames, photographs and lists of secret agents. Several of the documents are clearly labelled “To be burnt once the document has been read”.

The documents indicate how Poland was to help the Soviet Union invade Norway in the event that war broke out, how Poland recruited agents and pinpointed locations to bury weapons, and how they established so-called “sleeper agents” in Norway.

The agent with the codename Igor is now 63 years old. Dagbladet has not anonymised him, but out of consideration for the man’s family we have not used his surname. His real name, which he still uses every single day in Norway, is Tomasz.

We confronted Tomasz for the first time on 1 November 2017. We approached him in the car park outside the doctors surgery where he works, showed him documents with his signature on them and asked whether it was true that he was a Polish spy.

Tomasz categorically denied this

The Polish People’s Republic had friends in the East, enemies in the West, and was armed for war. The military intelligence service had a staff of 3200 and a secret number of spies. Poland was a communist one-party nation and part of the Warsaw Pact military alliance – the Soviet and Eastern Bloc’s answer to NATO.

Although Poland was an independent nation, it was to all intents and purposes controlled by the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union’s plans were Poland’s plans. A number of major military exercises with the Warsaw Pact countries repeated the same scenario for a new full-scale war: while the Soviet Union advanced west, Poland would occupy Denmark. From there the Polish troops would continue on to Eastern Norway by sea.

The documents show that agents at the Embassy of Poland in Oslo worked hard to map defences in Southern Norway. They had pinpointed several beach areas between Larvik and Sandefjord where the troops could land in the event that war broke out.

As far as Dagbladet is aware, the Polish agents were able to spy unimpeded. The Norwegian Intelligence Service says there is not one single document about Polish intelligence on Norwegian soil in their archives. The Norwegian Police Security Service writes in an email that they are unable to say whether they have information on individuals in their archives.

Tomasz came from Lublin, a medium-sized city in Poland a few tens of kilometres from the Ukrainian border, and had plans for his life. He was to be a doctor, just like his father. Tomasz was an only child and very ambitious. He grew up with his parents as part of the so-called intelligentsia – the status class of educated people – in post-war Poland.

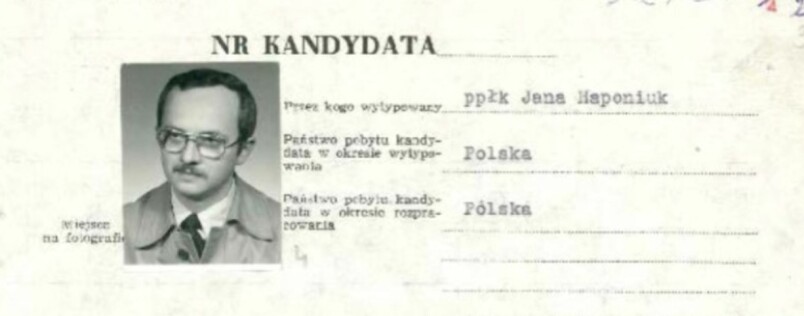

In April 1978, Tomasz was 21 years old and making good progress with his studies. He was chosen for a practical placement in Italy that summer and was therefore summoned to a meeting with Jan Haponiuk, who had been an experienced lieutenant-colonel and intelligence officer in the 60s, and who lived in Tomasz’s home city.

It was not always easy to get permission to leave Poland in the 1970s. Many Poles who travelled abroad never came home again, and it was people like Haponiuk who decided who was allowed to travel and who had to stay.

Haponiuk was impressed by the medical student. Tomasz showed him pictures and brochures he had been given during a military air display in the USA the year before while visiting an aunt in Philadelphia.

‘He has proven himself to be a resourceful student, willing to give us information of interest,’ Haponiuk wrote. He noted that Tomasz was a bright student to whom others at the university looked up, spoke good English and liked taking pictures.

Haponiuk was convinced.

‘We can use him in our future military intelligence,’ he concluded. In other words, if Haponiuk got his way, Tomasz would become a spy.

Tomasz arrived in Norway for the first time on 4 June 1984. He spent six months at the Women’s Clinic at Rikshospitalet in Oslo as part of an exchange agreement.

During this time, the intelligence service in Poland wanted him to make contacts, immerse himself in “the psyche and mentality of the people who live there” and find a woman to marry. Then Poland would have an operative agent who was a permanent resident of an enemy country posing as a doctor.

Tomasz was also asked to investigate the hospital he worked at to gain an overview of its wartime capacity and the progress it had made with scientific work on medicines to counteract radiation.

We do not know whether it was a consequence of the plan, but quite quickly after Tomasz arrived in Norway, he met a woman six years younger than him. She was from Poland, but resident in Norway, and they met at the Catholic church they both attended. She became the woman in Tomasz’s life.

They were married in Poland in 1985. Now, 33 years later, they are still married.

She was entered into the Polish intelligence system’s records as soon as they met. In a note written by the intelligence chiefs in Poland, it is recommended that all letters between Tomasz and she be monitored. All her family were to be reviewed to assess whether she was a suitable candidate to marry Tomasz.

Formally, Tomasz was still a voluntary informant for the secret services – but the Polish spy chiefs could tell he had greater potential:

‘Based on the candidate’s clear willingness to cooperate with us, I propose that we recruit him as an agent and prepare him to serve as a wartime radiotelegraph operator and a peacetime investigator of military objectives in Norway,’ it says in a report. This was written by intelligence chief Jerzy Gajewski in 1985, after Tomasz’s time at Rikshospitalet. Gajewski was Tomasz’s contact at the intelligence service – his so-called “handler”.

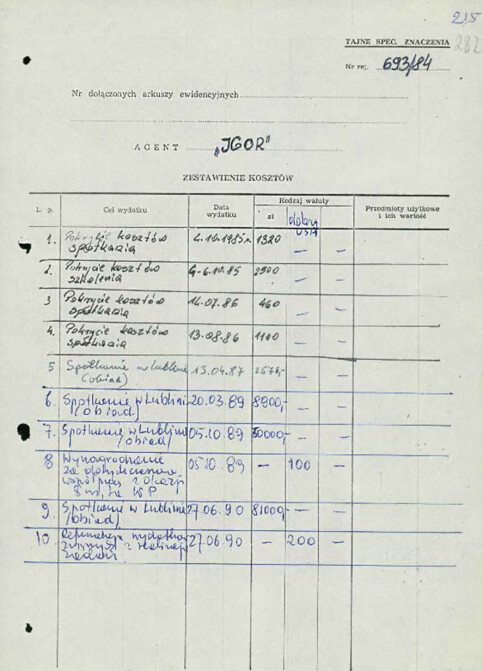

Tomasz continued to live in Oslo after his study period, but travelled back to Poland to meet with Gajewski several times in 1985. According to the reports, one of these meetings was particularly special. This took place on 4 October 1985, one year and four months after Tomasz had first travelled to Norway. He was 30 years old, had married in Poland the same summer, and his wife was pregnant with their first child. This was the day he formally became a spy.

According to Gajewski’s records, they met in Constitution Square in Warsaw. Gajewski noted that Tomasz was punctual, as always. To start they spoke in legendary bar Pod Kurantem, where the specialities hot beer and cake with chocolate cream have been served since 1953. The recruitment conversation then took place in one of the intelligence service’s secret meeting places.

There is a contract from this meeting bearing Tomasz’s signature.

‘The undersigned enters voluntarily into cooperation with the military intelligence of the Polish People’s Republic,’ it says in the contract.

He undertook to perform the assignments he was given loyally and conscientiously.

‘I understand that failure, cooperation with the enemy or the disclosure of state secrets is detrimental to the Polish state and will be punished.’

According to Gajewski, Tomasz signed the declaration willingly and said that he would perform the assignments he was given to the best of his ability.

Tomasz had not done any military service, but shortly after signing this contract, three days were set aside for training. This training was led by Gajewski. According to the course plan, it started simply enough with an introduction to terms and expressions, topography and map reading. It then moved on to how agents operate in the field: how to obtain secret information, how to lose pursuers, how to use cover stories and how to act around family, friends and colleagues. Finally, there was training on strategic targets in Norway, the Norwegian intelligence service and the organisational structure of the Norwegian military.

When the training was over and Tomasz was back in Norway, he began his double life as Igor, the secret agent.

Igor was not Poland’s only agent in Norway. According to the documents to which Dagbladet has access, they were well represented by agents with codenames such as Anis, Donar, Langeren, Magnet and Troll. What made Igor different was that his role was kept secret from the Embassy of Poland in Oslo, and from the other Polish spies. Igor’s orders came directly from Warsaw. Gajewski feared that anything else might lead to him being discovered. An agent such as Igor, with a cover story built up over several years, would be difficult to replace.

But Igor was monitored by Polish intelligence as well. Was he living at the address he had given? Did he live with his wife and mother-in-law? How did he behave socially? Who were his friends? Everything was reported back to Poland by other agents in Norway without these agents knowing why they were reporting on a doctor in Oslo.

In a report, the agent known as Anis wrote: ‘Since I sometimes come into contact with this person, it may be the case that I should not investigate him any further. My wife knows his wife.’.

Anis was told that he should under no circumstances avoid Igor in his private life, but that he should not make direct contact with him. According to several reports, Igor was asked to keep a low profile and to avoid close contact with Polish environments in Oslo.

Who he really was and the role that the intelligence service intended him to play was to be kept secret at all costs.

We approached Tomasz once again on 8 November 2017. He denied having been a spy and told us someone was trying to trick Dagbladet with false information. The next time we contacted him, we were told that all further communication would have to take place through his lawyer, Kjell-Ove Engeseth.

We approached Tomasz once again on 8 November 2017. He denied having been a spy and told us someone was trying to trick Dagbladet with false information. The next time we contacted him, we were told that all further communication would have to take place through his lawyer, Kjell-Ove Engeseth.

‘Dzień dobry,’ – ‘good morning’ – says a female voice on the entry phone. We are in the residential area of Rembertów just outside Warsaw on a December day in 2017. A two-storey house with white brick walls, red tiles and a paved driveway up to the garage sits behind the metal gate.

‘We’re trying to get in touch with Gajewski,’ we say.

He is one of the three people who signed most of the orders for and reports about Igor.

‘Gajewski’s not home,’ the woman says.

When we come back later, the curtains have been drawn. Gajewski replies to a text the same evening: ‘Unfortunately I can’t meet with you. I have a duty of confidentially that is still in effect. Please don’t knock on my door again.’

Konstanty Malejcyk, who became head of the Polish military intelligence service during the 90s, lives in another Warsaw suburb. No one answers when we visit Malejcyk. We put a letter through his letterbox explaining that we want to talk to him about his time in the secret services during the Cold War. Malejcyk has never got in touch, and Dagbladet has not managed to contact him in any other way.

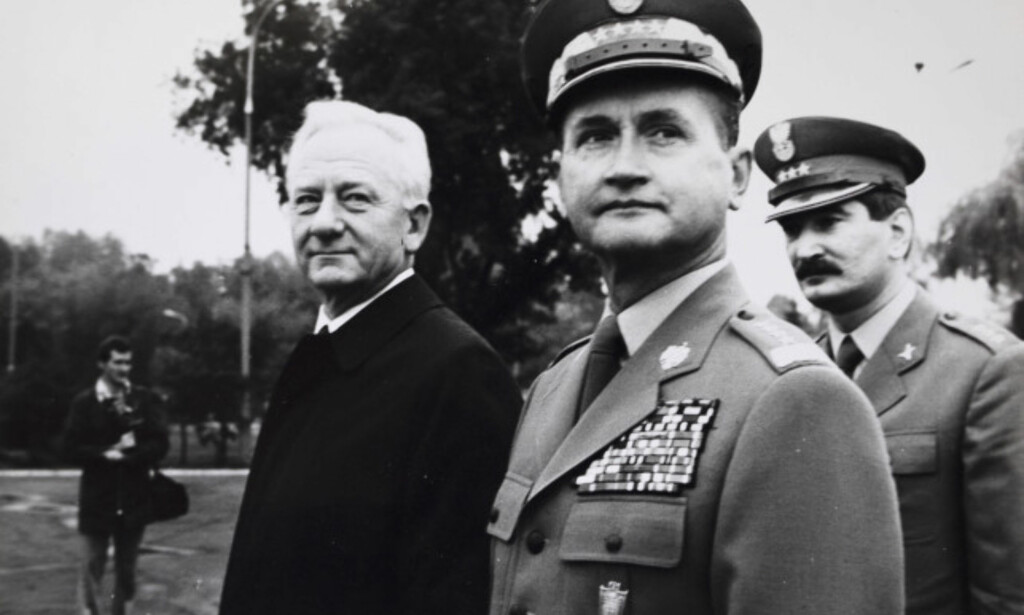

The last of the three military chiefs who worked closely with Tomasz is Jerzy Gryz. According to the documents, Gryz was Tomasz’s handler from 1989 until 1991.

Back then, Gryz was among the elite in Poland’s secret services. He is now 68 years old and teaches Norwegian to Polish women with husbands in Norway.

Gryz is standing out in a field next to his low brick house just outside Lublin. He has put on his old military uniform. The jacket is too big for him now, and his moustache is grey.

‘We were lucky,’ Gryz says in fluent Norwegian. ‘We had our plans. You Norwegians had yours. It was good we never had to execute them. No one hates war as much as those who have to fight them.’

Gryz has lived a long life in Poland’s service. As a teenager, he was among a select few who were able to stake out a career at the top. During the Cold War, the Eastern Bloc countries sent their promising young people to the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO), often called “the Harvard of Russia”. Poland sent Jerzy Gryz.

He was 19 and dreamed of learning Spanish, travelling to Latin America and fighting like Che Guevara, but was given the choice between Finnish and Norwegian. Gryz chose Norwegian. For five years, from 1968 to 1973, he read Norwegian books and learned about Norwegian culture and customs.

Nevertheless, when he was given a place at the summer school at the University of Oslo in 1974, he was far from fully qualified. He barely understood the language and everything seemed foreign.

‘I discovered you ate your food completely raw. Carrots and vegetables straight from the earth,’ he says. ‘You didn’t boil them like we do in Poland.’

But he remembers the biggest difference was the way people walked.

‘Norwegians walked slowly, in a relaxed way. In Poland people walked more determinedly, with quick steps.’

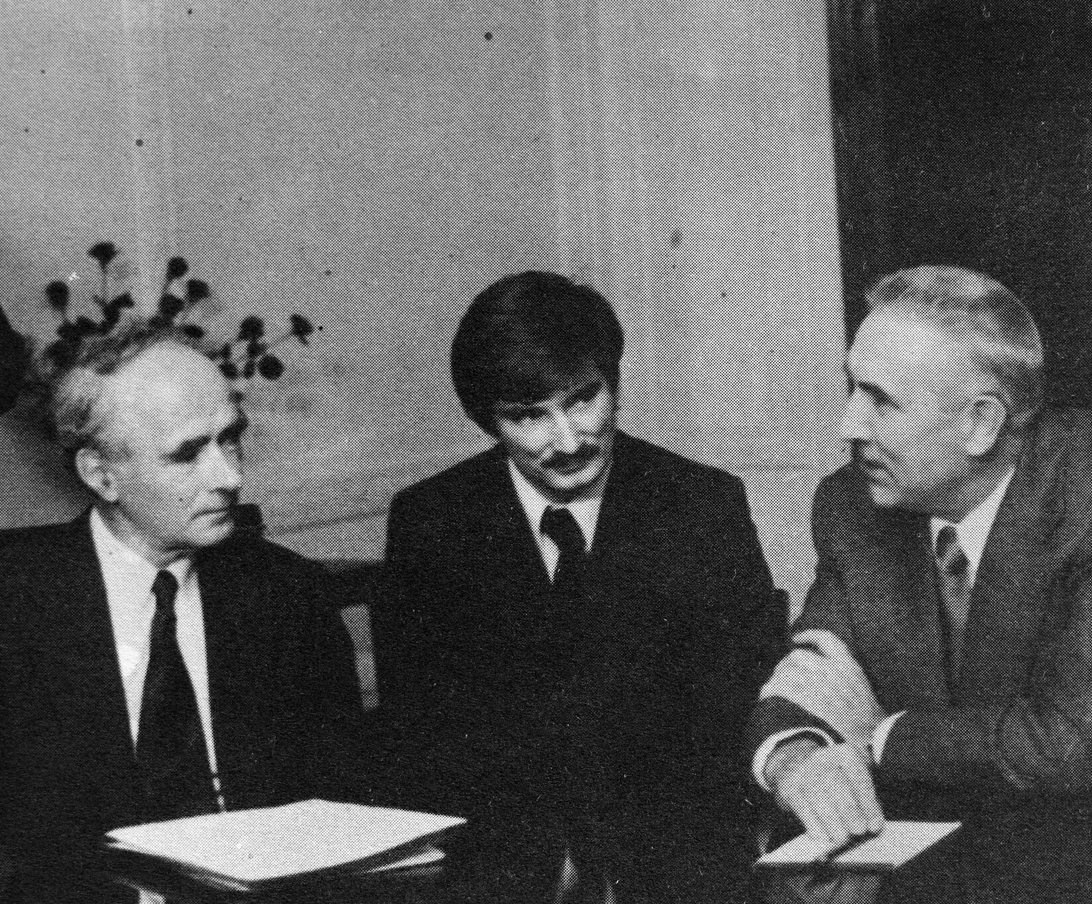

After his studies, Gryz worked at the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs alongside the most powerful people in Poland. When the Prime Minister of Poland was in Norway in 1975 to meet Prime Minister Odvar Nordli, Gryz acted as interpreter for the two heads of state.

‘We were all the way up on the 16th floor, in the Prime Minister’s office in the Høyblokka building. The view was spectacular,’ Gryz says.

A few years later he landed a permanent job in Norway as the Polish military attaché’s second-in-command in Oslo. Gryz settled in Ekeberg with his wife and three children. He did not stay in Norway long. His wife fell severely ill only a year later. The family moved back home and his wife died shortly afterwards, leaving Gryz alone with the children.

Gryz maintained his close relationship with Norway. According to the documents that Dagbladet has read, from 1980 he was responsible for recruiting agents and leading a network of Polish spies in Oslo.

A plan was made to establish caches of radio equipment, weapons and other military equipment that could be used in the event that war broke out and Poland invaded Norway. According to the documents, Gryz continued to lead secret operations against Norway until at least the spring of 1991.

Gryz speaks eagerly and in detail about his visits to Norway in the 70s, but when we ask about the content of the documents, intelligence against Norway and the agent with the codename Igor, he is suddenly unable to remember anything.

– ‘That may have been the case,’ is all he says.

– ‘Do you recognise the name in the documents?’

– ‘No. I don’t know what any of that’s about.’

– ‘But isn’t this your signature on a lot of them?’

– ‘I don’t know.’

– ‘You even recommend military and weapons training.’

– ‘I don’t remember. I don’t know anything about this.’

– ‘Did you work for the military intelligence service?;

– ‘Yes, I did.’

– ‘What did that involve?’

– ‘All sorts of things.’

– ‘Do you remember the agent with the codename Igor?’

– ‘I don’t remember that situation.’

– ‘Were there many situations like that?’

– ‘I don’t know. It was 30 years ago, you know.’

– ‘Why won’t you tell us anything about it?’

– ‘I can’t tell you anything about it.’

– ‘Can’t or won’t?’

– ‘I can’t because I don’t remember any such situations.’

– ‘But you remember a lot of other things.’

– ‘I remember what interests me. A person’s memory is designed to forget what it doesn’t need to remember. You remember some things and you forget other things that you don’t need.’

On 2 January Dagbladet received an email from Tomasz’s lawyer:

‘We have once again discussed the case in light of the contact and correspondence we have had. Tomasz has decided he does not want any further contact with you.’

It could have been a parody of a spy thriller: a man wearing a black trench coat and matching black leather gloves. But that was how Jerzy Gajewski was dressed when he went to meet the spy he had given the codename Igor. The meetings where Igor and his handlers exchanged information always took place in Poland.

If an extraordinary meeting was required, Igor would send a letter via a contact in Gdansk using the codename “the Sailor”. Igor would say he had been fishing. The number of fish he had caught was code for how many months it would be until he came to Poland.

If there was an “urgent and sudden need” for a meeting, an intricate security procedure had been established to arrange for such to take place in Oslo.

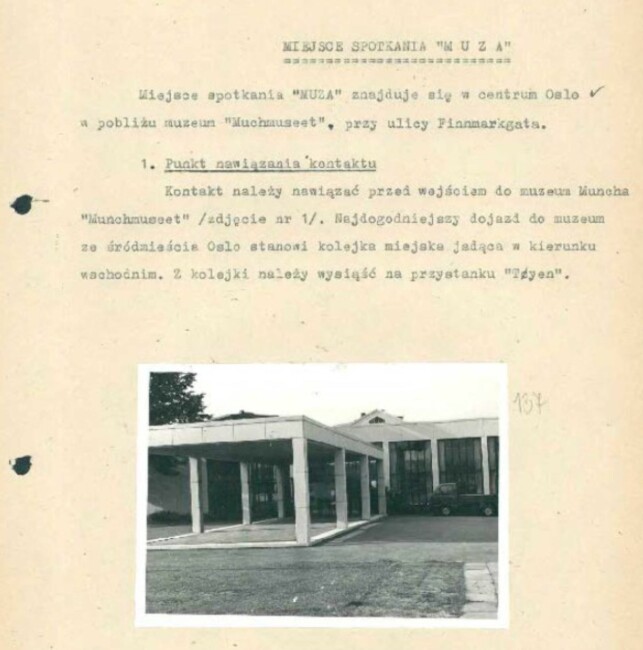

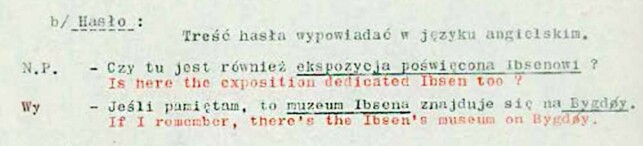

The summons was a handwritten letter sent from Stockholm. It would appear to be from a close friend and detail everyday victories and challenges. The secret signal was the date on the letter. The month would be written in letters, not numbers. The meetings would always take place at midday on the second Saturday of the following month.

The meeting place was at the entrance to the Munch Museum in Tøyen. If Igor was holding a rolled-up copy of VG in his left hand, it was safe to meet. If it was in his right hand, there was danger afoot.

The other agent would identify themselves by asking: ‘Is there an Ibsen exhibition on here too?’ Igor would confirm who he was by replying: ‘If memory serves me correctly, the Ibsen Museum’s on Bygdøy.’

In the event of an emergency, Igor might also be called or sought out without warning. In such cases, the code was ‘Ajax says hello’.

Ajax was the name of Tomasz’s dog, which died in 1985.

His first period in Norway as Agent Igor, from December 1985 until the summer of 1986, is described in a handwritten report from Tomasz. In this, he says that he was politely received when he went to the police station to obtain his residence permit, that he has become father to a little boy and that he has bought a Volvo.

The report also indicates how Tomasz immediately started to think, observe and behave like a secret agent. He attended a Norwegian course at Rosenhoff School five times a week and there was an American in his class that Tomasz thought ‘was trying to pass for a priest’.

‘He was 58–60 years old, tall, quite slim, grey-haired, had a side parting and wore glasses,’ Tomasz wrote.

The American was often absent from the Norwegian course and ‘excused himself by saying he had to travel to Bergen, London, etc.’. It was during one of these supposed trips that Tomasz spotted him at a flea market in Bekkestua ‘together with American military personnel’.

Tomasz observed the American for six months and was, according to the report, convinced that he was working for the CIA. His handlers at home in Poland asked Tomasz to keep his distance. They did not want a CIA agent anywhere near Igor.

The American’s full name is given in the documents. He died in 1988. Dagbladet has not managed to track down his family.

«I’ve never heard anyone say and never had the feeling that he had any hidden agenda.» Kjell Erik L’Abee-Lund, tidligere bydelslege, om Tomasz

Kjell Erik L’Abee-Lund (74) is now retired, but in 1989 and 1990 he worked as a district doctor at Ryen Health Centre in Oslo, where he was responsible for a Polish house officer who had come to Norway five years earlier.

‘Tomasz seemed nice enough,’ he says. ‘I don’t remember enough to give you any specifics, but he was neither exceptionally skilled nor someone I worried about.’

L’Abee-Lund says that Tomasz left his district at the end of his placement, but that they sometimes bumped into each other and said hello.

‘I’ve never heard anyone say and never had the feeling that he had any hidden agenda.’

A Polish intelligence document from 1990 names L’Abee-Lund as Tomasz’s supervisor during his placement as a house officer. In the same document, a major and a lieutenant-colonel conclude that ‘Igor has now arranged his situation (…) so that he will be able to carry out assignments during wartime’.

Tomasz had lived in Norway as a secret agent for almost five years and planned to open his own surgery. He was also approaching the number of years in Norway required to apply for citizenship.

The spy chiefs deemed Tomasz’s adjustment period over. So far, they wrote, he had ‘met more or less all his targets’.

Tomasz had done more than just adjust. In the file of information he shared with his handlers at the end of the 80s, it says that he reported back on military objectives in the Strømmen and Lillestrøm area – a military airbase, among other things. The documents to which Dagbladet has access do not say what type of information he provided.

Several people are named in the documents. Tomasz reported on a person he suspected of cooperating with the Norwegian security police, he contributed information on a Pole the intelligence service was considering recruiting as an agent, and he provided information on the people with whom he was friends. Dagbladet does not know whether there were any consequences for the people he named.

According to the documents, 1989 seems to have been the year of Agent Igor’s greatest triumph. This was when he claimed to have discovered a secret British intelligence base.

At that time, Tomasz worked at Dikemark Psychiatric Hospital, and according to the report he observed the head office of oil company Fina in Asker every day while travelling to and from work.

‘In the morning many cars drive to this address (different cars each time) with British and Norwegian number plates. (…) This is most likely a secret centre for British intelligence.’

The documents seem to suggest the spy chiefs in Poland concluded his assumption was correct.

Fina was bought by Shell in 1999. Dagbladet has been in touch with former employees. None of them know about any British intelligence base, but point out that there were a number of different lessees in the office building owned by Fina. The Embassy of the United Kingdom in Oslo has not responded to Dagbladet’s enquiries.

The final notes on Agent Igor, written by his handler Jerzy Gryz in October 1990, map out Igor’s future. They detail how he will spend the following summer receiving military weapons training and being taught about radio communication and exchanging information during wartime as well as receiving training in intelligence assignments and information on ‘the Norwegian Armed Forces’ armament and plans’.

After this, Igor would be ready to take on ‘a military role at an outpost in Scandinavia’, a role for which Gryz thought he met ‘virtually all the prerequisites’.

‘Based on the information we have available, we can conclude that there is no reason to doubt Igor’s security status or loyalty to us,’ Gryz wrote. According to the report, their next meeting was to take place in the spring of 1991, in Tomasz’s hometown of Lublin.

This is the final entry in the documents on the Agent Igor. The documents the Polish government have made public only go up to January 1991. The Soviet Union and the defence alliance into which Poland had entered, the Warsaw Pact, broke down later that year.

There is no information on what happened to Igor, on whether his activities were wound up and, if they were, how this came to pass. Only one person can tell the whole story of how a young, ambitious student ended up an enemy spy in Norway with the pretence of being a doctor and GP. Igor himself.

On 12 February, Dagbladet received an email from Tomasz’s lawyer, Kjell-Ove Engeseth. The lawyer wrote that Tomasz ‘is currently in Africa (…) he would like to talk to you’. When Dagbladet called, Tomasz said the following:

‘I’ve been thinking about this and decided it’s best we meet. I think I have a story you’ll find exciting.’

We met at Dagbladet’s office in Hasle in Oslo on Wednesday 21 February.

«I UNDERSTOOD WHAT HE WANTED, AND I HAD NO CHOICE.

IF I SAID NO, I'D NEVER BE ABLE TO LEAVE POLAND.» Tomasz

‘I never thought I’d talk about my years as an agent,’ he begins. ‘Then this happened.’

A thick file containing the documents from the Polish military intelligence service lies on the table in front of him. His name, Tomasz, is written on the cover. When he reads something with which he doesn’t agree, he exclaims ‘idioti!’ or ‘absurd!’. Other times he says ‘yes, that’s accurate, or ‘that’s true’.

He confirms that it is his signature on several of the documents, that he provided information to the intelligence service in Poland and received money from them to cover his expenses.

The first couple times we met him, when he denied everything, threatened to take us to court and said the documents were fake, he was under a lot of pressure. Now, as he flicks through the papers, he seems relieved. Tomasz says he has a recurring nightmare in which he is attacked and taken away by men in green uniforms.

‘I’ve been having it for decades,’ Tomasz says.

Tomasz has told both his wife and two children – both of whom are adults – about his past as a Polish spy. He says he told his wife many years ago and that she has now promised him: ‘What happens, happens. I’ll weather the storm with you.’

‘My children say: “Dad, the war’s over. Poland’s independent. You live in Norway, an independent country. No one cares anymore”,’ Tomasz says. ‘It wasn’t until then that it truly sunk in for me that the Cold War is over.’

He says the most important reason why he has decided to talk to Dagbladet is his love for his wife. In one of the documents Dagbladet sent him earlier this year – the instructions he was given the first time he travelled to Norway – the Polish intelligence service describes the plans they had for Tomasz’s love life: ‘It would be advisable for you to find someone to marry among those whose acquaintance you make’.

‘That’s as far from the truth as it’s possible to get,’ he says. ‘I’ve been with my wife for 36 years – she’s the love of my life. And it is love, not part of any plan hatched by the Polish intelligence service. I couldn’t stand the thought of that being sullied. I knew I needed to come clean.’

He has been afraid of what would happen if he was found out for many years. Afraid of ending up in prison, afraid of being killed, afraid of never being able to travel back to Poland. Now he hopes there will no longer be anything to fear.

‘Maybe people would rather hear my story,’ he says.

Any crimes Tomasz may have committed in Norway as Igor are now statute-barred, which means he cannot be punished for them. He says he hopes his patients will still trust him.

‘I hope they understand I’ve never broken their trust,’ he says.

The story Tomasz tells about how he was recruited, why he did not say no and what he has done as a spy in Norway starts in 1982, with a punch that broke both his glasses and his resistance.

The fist that hit him in the face belonged to lieutenant-colonel and intelligence agent Jan Haponiuk – the man who decided which people in Lublin were allowed to travel out of the country.

Tomasz says that what is written in the documents is true, that he did meet with Haponiuk in 1978 and showed him nine photographs and some brochures that he had taken from an air display at an American military base. According to Tomasz, Haponiuk had heard that he had visiting his family in the USA and wanted to know whether he had anything interesting to show for it.

‘They were just normal brochures. They gave them out to all the spectators,’ Tomasz says.

Haponiuk was nevertheless impressed. Tomasz remembers that he ‘got really worked up and bounced up and down in his chair’. He thinks it is because of the pictures and brochures that Haponiuk got in touch four years later to summon him to his office once again.

‘By then Haponiuk had spoken to his superiors in Warsaw and wanted to make me head of a company in the US. You couldn’t travel more than 50 kilometres from the embassy on a Polish diplomatic passport, but if I were an ordinary civilian employee, I would be able to travel around and observe military objectives,’ Tomasz says.

According to Tomasz, during this meeting Haponiuk was in a very good mood and produced a bottle of vodka for them to share in his office. Tomasz claims that he, back then as he does now, ‘hated communism’.

‘We got very drunk. In the end I said: “I’ll never work for Russia or a communist country”. Haponiuk went nuts. He was furious. He leapt to his feet and hit me twice. Called me a traitor. He broke my glasses and dragged me out of his office.’

According to Tomasz, he had no way out of Poland after this. He says he applied to travel to Austria and to South America, but his applications were rejected.

‘I was out in the cold,’ he says.

Tomasz describes the next two years as tough. He continued working as a doctor in Lublin, but dreamed of getting out of Poland. Tomasz was 29 years old and, according to the man himself, ‘lonely and vulnerable’. His father had cancer and was close to death.

When the opportunity to travel out of Poland finally presented itself, at first it just seemed to be a coincidence. Tomasz is no longer sure it was. He was offered the opportunity to practise in Norway for six months, completely out of the blue.

‘I think the intelligence service must have had a hand in it – they must have made sure I was chosen,’ he says.

Then Lieutenant-Colonel Haponiuk called. Tomasz had not seen Haponiuk since he had hit him, dragged him out of his office and shouted ‘Traitor!’.

‘He said: “We’ve heard you plan to travel abroad. There’s a person I think you should meet.”’

Tomasz says he met the two men, Haponiuk and another, in an apartment building. The other man introduced himself as “Gorecki”. His real name was Jerzy Gajewski. He would later become Tomasz’s handler.

‘I knew what he wanted and knew I didn’t have a choice. If I said no I’d never be able to leave Poland,’ Tomasz says. ‘It was a different time. I couldn’t envisage the military dictatorship ever falling.’

The documents Tomasz signed before he travelled to Norway gave him ten specific assignments including ‘collecting information about people with access to interesting intelligence material’ and ‘investigating your workplace (…) and the function these facilities will have during the war’.

‘I didn’t see what was written in the documents,’ Tomasz now claims.

He says the documents were produced just before the meeting ended and he was told to sign them.

‘Do you think anyone will believe that?’

‘It’s the truth. People can believe what they want.’

– Tomasz

Tomasz’s own story of Agent Igor, which he has told Dagbladet over the course of several interviews in recent weeks, differs from the documents in several important respects.

In the documents, Tomasz comes across as a loyal agent from his first contact with the intelligence service in 1978 until the final notes from 1990. The chiefs describe him as patriotic, committed to the intelligence work and willing to perform assignments in peacetime and wartime. However, Tomasz claims that he was just playing along and that he wanted nothing more than to be released from his cooperation with the intelligence service.

‘The plan was always to be smarter than them. I was going to wait until I became a Norwegian citizen and then tell them to stick their contract up their arses.’

He says it was impossible for him to just jump ship because he had a wife and children as well as family in Poland.

‘It wouldn’t have been safe. You have to remember Poland was a military dictatorship. You had to be careful.’

Even so, Tomasz says he took measures to resist the orders he received from the intelligence service. As part of his contract he was supposed to send coded messages to the headquarters in Warsaw in the form of postcards. But none ever arrived. Since Igor was someone they trusted, this sent alarm bells ringing.

The documents describe a major inquiry to find out whether there were disloyal servants in the ranks or whether the Norwegian intelligence service had intercepted the messages. They concluded that the postcards had probably been lost in the Polish post, whereas in actual fact, Tomasz never sent any.

‘It was a silent protest,’ he says.

Tomasz says that he needed to give the impression he was a loyal agent for his own safety. This is how he explains the documents detailing how he provided information about military objectives in the Lillestrøm and Strømmen area.

‘They asked me to look for some NATO installations. I told them about a model of a plane in Lillestrøm, but it was just a model. I never gave them any reports,’ he says.

Tomasz claims the information about a potential British intelligence base at Fina’s offices in Asker is just something he made up on the way to work.

‘I was in a traffic jam and I noticed several cars with the steering wheel on the right turning off. That was what I reported. I had to give them something,’ he says.

Tomasz claims that the note describing the types of cars arriving in detail and asserting the likelihood of this being a base for British intelligence did not come from him – even though the documents indicate it did.

‘I never did any observation work there. They must have sent someone from the Embassy based on what I told them,’ he says.

There are several things Tomasz denies or claims are greatly exaggerated in the documents. He says the ‘spy training’ described in a two-day course plan actually only took an hour and a half. There are also several names he denies having given to the intelligence service, including two Polish citizens who are singled out as political refugees.

‘This is just nonsense. I’ve never heard of any of them,’ he says.

But he admits to providing information on some of the people mentioned. One of them was a member of the Polish community in Oslo, and according to the documents he was being assessed as a potential agent. Tomasz described him as ‘reserved’, ‘egotistic’ and ‘greedy’.

Dagbladet has been in touch with someone with the same name who says he lived in Norway in the 80s. The man says he has never had any contact with Polish intelligence.

‘I regret naming names now,’ Tomasz says.

He claims he never said anything that would put the people he named in any danger, but the documents show that the intelligence service initiated extensive investigations.

‘I didn’t know which techniques they used. It’s only now I’ve seen the documents detailing how they checked up on entire families that I see the consequences. It’s terrible,’ he says.

The conversations during which he provided information often took place in restaurants. He and his handlers, Gajewski and Gryz, liked to eat steak tartare and drink vodka.

‘I just told them what I thought they wanted to hear,’ Tomasz says.

‘Did you say more than you should have?’

‘Well, I suppose I might have. I’m not proud of what I did. The people I met with, who sat across the table from me, were always well prepared. They were well trained. It was idiotic of me to think I could be smarter than them.’

Of everything in the 300 pages on Agent Igor, there is one thing in particular that Tomasz is keen to repudiate. In a document from October 1989, handler Jerzy Gryz has written that Igor will use his position as a doctor to identify employees in the Norwegian Armed Forces: ‘It would make it easier (…) if they do not pay for their appointments there and then but are sent invoices to be paid by the Norwegian Armed Forces’. The documents say that Tomasz worked in the ‘psychiatric department’ at that time, but they do not say where.

‘I never, never provided information on my patients. That has always been inconceivable to me. I have never done anything to break doctor-patient confidentiality.’

Tomasz does not want to tell Dagbladet when he worked at which surgery or hospital, instead just saying it is nonsense that he identified employees from the armed forces.

‘I was working in a hospital at that point and all my patients were inpatients. They weren’t sent invoices, so it would have been impossible to do what’s described in the documents.’

‘Did you tell your bosses in the intelligence service that you wouldn’t give them information on your patients?’

‘Yes, I did.’

There are no notes in the documents indicating that Tomasz refused to provide information on his patients. The only reference Dagbladet has found to him asking to be excused from something involved breaking into military installations to which he did not have access. Tomasz himself claims he told them he would not ‘spy on Norway’.

The instructions Tomasz signed before travelling to Norway specifically ask him to investigate how much progress Norway had made in terms of treating flash burns.

‘All doctors travel and share their experiences. Medicine isn’t secret, it’s about sharing and exchanging. So I said I’d tell them if I heard anything,’ he says.

‘Did you hear anything?’

‘Is there anything in the documents? No? Then there’s your answer.’

There is nothing in the documents on Igor about state secrets or meetings with Norwegians in senior positions in the government or authorities. It is also clear that this type of spying was not what Igor was recruited for.

Igor was first and foremost a “mobilisation agent”. When war broke out between the Soviet Union and the West, he would step out of his role as a perfectly integrated Norwegian and start reporting on what was happening behind enemy lines.

When Tomasz reads the documents, he says he was unaware he was to have a role in a potential war.

‘It’s just nonsense. I wasn’t expecting any war. Of course I wasn’t,’ Tomasz says. ‘If they’d mentioned anything like that to me, I’d have said no.’

Tomasz claims that the “extensive training” he is described as having undergone in the summer of 1990, when Igor was to be trained as a wartime radiotelegraph operator and to use weapons, never happened.

‘I was offered two to three months of training in Kiejkuty, a secret training centre for agents. But it was completely out of the question for me to go there.’

However, what he does confirm is that he himself asked ‘to visit a firing range’. This happened when Jerzy Gryz took over as Tomasz’s handler in 1989.

‘He asked whether there was anything he could offer me, and that’s when asked about it,’ Tomasz says.

‘Why did you want to go to a firing range?’

‘I’d never fired a gun before and thought it might be fun to try.’

Tomasz says nothing ever came of it because Gryz could not find a firing range anywhere nearby. Instead, Gryz visited Tomasz on one of the occasions he was at home in Poland and showed him how to change magazines and load a gun.

‘Did you have access to weapons in Norway?’

‘No. And I don’t know anything about weapons either.’

Who was Agent Igor, really? Today it is impossible to know which version of the story is true, since Tomasz and the documents tell different stories. The old spy chiefs in Poland are either dead, as in the case of Jan Haponiuk, completely refuse to talk to Dagbladet, as in the case of Jerzy Gajewski, or do not want to comment on the content of the documents, as in the case of Jerzy Gryz.

The old intelligence chiefs, many of whom enjoyed careers at the very top of the Polish military after the Cold War, may have had their own reasons for exaggerating the importance of the agent they called Igor and the job he did for them. A successful agent who showed great potential could be a ticket to status and higher positions for the officers responsible for him.

There are also many possible reasons why Tomasz himself would try to downplay his role. He has been involved in intelligence operations against a country in which he now lives as a citizen. A country he, according to the documents, was willing to betray in the event of war. And he still works as a doctor – a profession where it has to be possible for the people he meets to trust him.

‘Why should we believe your version of events and not what’s written in the documents?’

‘Just look at what’s written in those documents. What have I done? How much damage have I done Norway? I was always on my guard, thinking about what I could and couldn’t say. I told them things I knew wouldn’t hurt others because I had to give them something. Do you think I could have just asked them to leave me alone? No, no, no. I could have been arrested, my family could have been arrested. I can’t explain how much it cost me to meet with them again and again and keep up the pretence. It was a horrendous thing to live with,’ Tomasz says.

Tomasz and his family visited Lublin during the autumn of 1990. The world was changing. The Berlin Wall had been torn down, the Soviet Union was on the verge of collapse, and free and fair elections had been arranged in Poland for the first time since the Second World War. Trade union leader Lech Wałęsa was standing to be the country’s next president.

‘Everything was coming undone. The time of the generals was over,’ Tomasz says.

It was during that family visit to Poland that he met with his handler, Jerzy Gryz, for the last time, at a restaurant in Lublin.

‘“We’re entering a new era,” he told me. “Tomasz, if we ever meet again, pretend we’ve never met before.”’

They exchanged a firm handshake.

‘He said all the documents would be burned and that I didn’t need to think about what had happened anymore,’ Tomasz says. ‘It was over.’

« Sleeper agents who were posted abroad by Warsaw Pact countries and the Soviet Union. We don’t know the scope of it, but I think we can assume there were hundreds of them» Ørnulf Tofte

Almost 30 years have passed since the Cold War ended. Poland has switched sides and is now allied with Norway in NATO. When Dagbladet met with Jerzy , he said that he had been part of the group of senior Polish military personnel invited to the nuclear-proof military rock cavern in Bodø in 1997.

‘Our old friends had become our enemies, and our old enemies our friends,’ Gryz said.

For some people, the Cold War never ended. It has taken root as suppressed fear and revisits them during the night in the form of nightmares about men in green uniforms.

Ørnulf Tofte (96), who was head of Norway’s counter-intelligence until 1987, says he thinks there are more people like Tomasz.

‘Sleeper agents who were posted abroad by Warsaw Pact countries and the Soviet Union. We don’t know the scope of it, but I think we can assume there were hundreds of them,’ he says.

«Hi, Tomasz. You’ve worked for us before. Isn’t it time we sit down to discuss working together again?»

One of the first things Tomasz said when we met him was: ‘In a way I knew it would come to this. That it would never end.’ The question is whether it ever does.

In 2007, Tomasz received a phone call. He says he does not know who the caller was, whether it was a former colleague or someone who had seen his file, but it was a man’s voice.

‘Hi, Tomasz. You’ve worked for us before. Isn’t it time we sit down to discuss working together again?’ Tomasz replied that this was ‘completely, completely out of the question’.

He received another call in 2014. Same question. Same response from Tomasz.

Agent Igor no longer exists. He is just a name, among many, in old archives where secrets were left to die with the label “To be burnt once the document has been read”.

Despite numerous enquiries, the Polish authorities have not answered Dagbladet’s questions about intelligence operations against Norway either before or after 1990.

Marcin Krasnowolski and Agnes Banach have assisted Dagbladet with translations and interpretation.