Frida Kahlo is undoubtedly one of the most recognizable artists of our time. She is familiar to many in large part due to “Fridamania,” which developed over the last few decades and focuses on her cultural persona, which is intrinsically tied to the large number of self-portraits she produced in her lifetime. However, few are aware of Kahlo’s role as a teacher and her viewpoints on how one learns to be an artist.

La Esmeralda School

Kahlo began teaching young children as early as 1928. Later in 1942 the school La Esmeralda (previously known as the Ministry of Public Education’s School of Painting and Sculpture) opened. For a decade, Kahlo was registered as a teacher there, and in the first three years, she taught in a more formal capacity with 12 hours of teaching for three days a week. As author Hayden Herrera explains in Frida: The Biography of Frida Kahlo, “Frida adored children. She treated them as equals, and both in her art and in life she allowed them their own special dignity…her approach to her pupils was both that of a child among peers and that of an adult not wanting to ‘spoil’ youthful creativity.”

Many students at La Esmeralda immediately gravitated towards the vivacious and humorous Kahlo while a few others expressed skepticism since she lacked a teaching specialization. Kahlo addressed her background outright and her beliefs in a straightforward way. According to Herrera, Kahlo once said:

Well kids, let’s go to work; I will be your so-called teacher, I am not any such thing, I only want to be your friend, I never have been a painting teacher, nor do I think I ever will be, since I am always learning…I will never take the pencil from you in order to correct you; I want you to know, dear children, that there does not exist in the whole world a single teacher who is capable of teaching art. To do that is truly impossible.

Kahlo and the other teachers at La Esmeralda believed the entirety of Mexico to be an artist’s studio, and encouraged students to seek out and explore the streets and fields of the country. Above all, it seems that Kahlo wanted her students to be self-critical, and to approach every facet of life with aesthetic considerations. Herrera quotes a pupil named Fanny Rabel saying: “[Kahlo] did not influence us through her way of painting, but through her way of living, of looking at the world and at people and at art.”

Kahlo’s approach to teaching was not solely focused on observing the places within which she and her students lived and worked. She also encouraged students to learn from a variety of disciplines such as literature, art history, and biology. She often suggested students read the works of Walt Whitman and Vladimir Mayakovsky, and encouraged students to sketch pre-Columbian sculptures as well as colonial art from museums. Kahlo was even known to show her students slides under a microscope so that they could learn about microorganisms, plants, and animals.

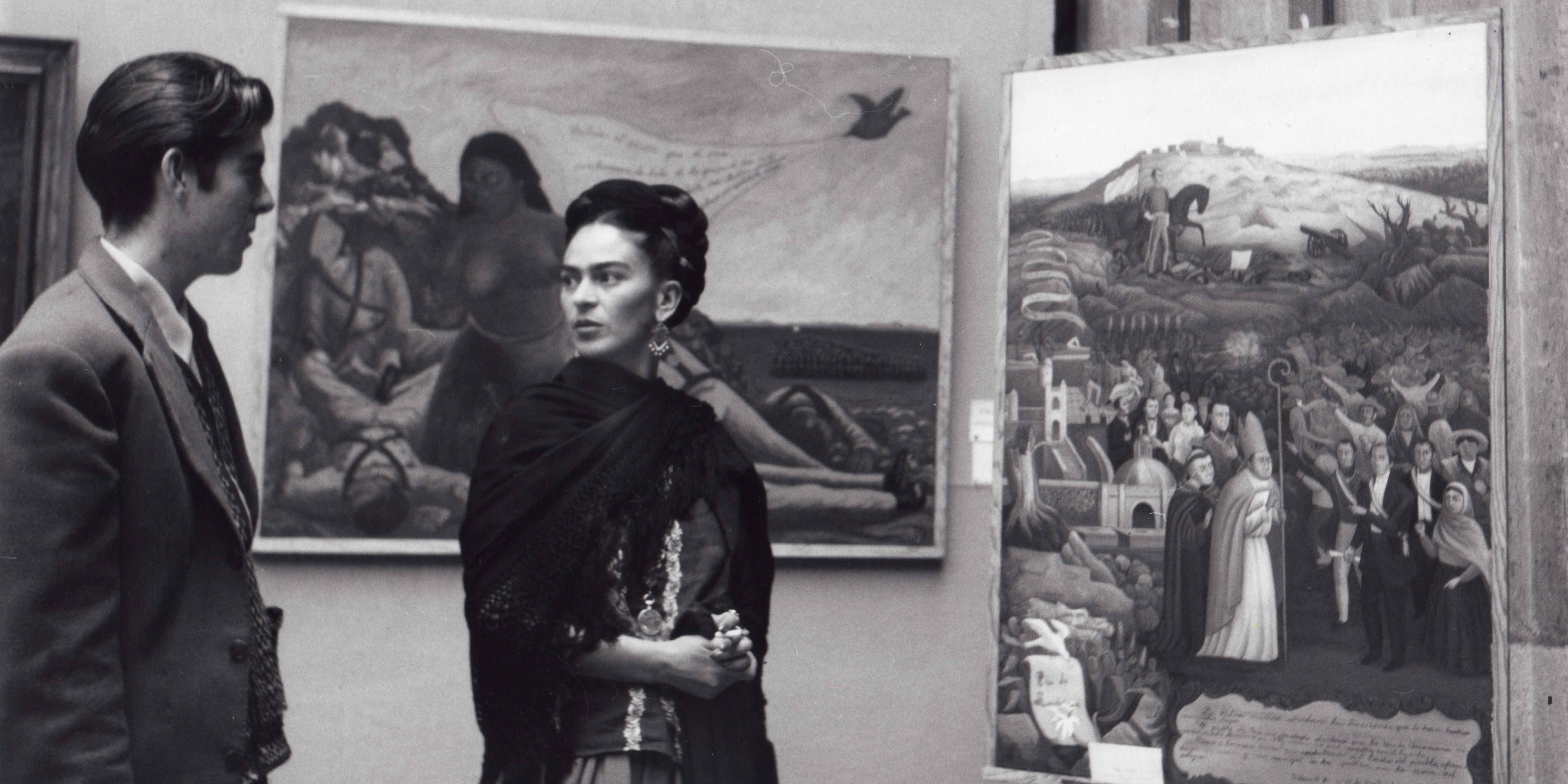

Lola Álvarez Bravo, born 1903, Lagos de Moreno, Mexico; died 1993, Mexico City. Arturo Estrada and Frida Kahlo in Exhibition, 1944. Gelatin-silver print. New York, Throckmorton Fine Art. © Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Image courtesy Throckmorton Fine Art, Inc.

Los Fridos

Kahlo nurtured the lives of young children and several older students as well—most notably “Los Fridos,” which was a group of artists who studied under Kahlo and became close friends with her until her death. Los Fridos included Arturo Garcia Bustos, Guillermo Monroy, Fanny Rabel, and Arturo Estrada. These artists collaborated on projects, and their work was also included in joint exhibitions.

The genesis of this particular group of artists began when Kahlo secured a mural project for them to paint on an exterior wall of a tavern, La Rosita, which was located close to La Casa Azul. There was a large party to celebrate the students’ success and, according to Herrera, Kahlo spoke to a reporter explaining that “she hoped this crusade in favor of art would result in a resurgence of spontaneity and of pure art, since the disciples will paint in the open air and in an atmosphere where sincere criticisms will cause them to improve their styles.” This quotation demonstrates Kahlo’s approach to teaching and cultivating strong artists who can learn and grow from criticism. After the success of the La Rosita murals, Kahlo secured other mural projects for Los Fridos and worked with them to find various art-related jobs like artists’ assistants.

While Los Fridos began as a group of just four pupils, it grew into an organization of politically active painters known as the Young Revolutionary Artists with 47 members. Kahlo’s guidance, resiliency, strength, and political interests had a lasting effect on these artists.

As a teacher, Frida Kahlo provided students lessons about how to look at the world—not just how to go about creating art. She treated her pupils as if they were members of her own family and nurtured their creativity up until her death in 1954. She demonstrated a strong emphasis in exploring how cultural aspects of her life and the lives of her students were depicted in society, and prompted students to be curious in their artistic, professional, and personal pursuits.