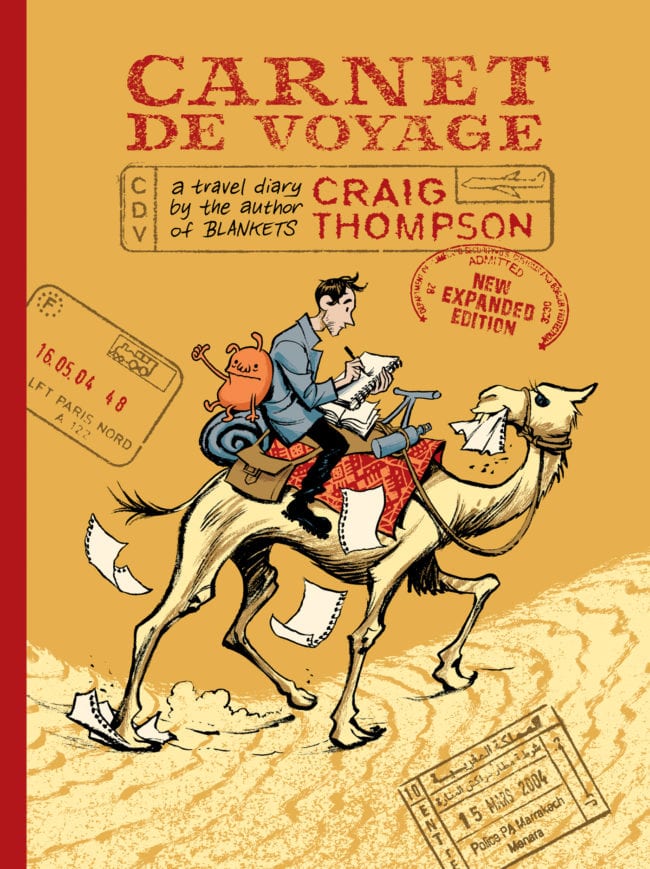

When Craig Thompson’s Carnet de Voyage was released in 2004 it was a book that was immediately beloved by a lot of readers, and by a lot of artists as well. The book reproduces pages of Thompson’s sketchbook on a trip through Europe and North Africa following the release of Blankets while he was on an extended book tour and vacation. Since the book was initially released, Thompson has published Habibi and Space Dumplins, and now Drawn and Quarterly has published a new hardcover edition of Carnet. The edition includes new pages drawn to give some background about Thompson’s first trip to France as well as a more recent one and gives some information about how the book was made. I’ve loved the book since it was first published and though I’ve interviewed Thompson in the past, I wanted to talk about drawing from life, the practice of keeping a sketchbook, and how it’s unlike making a comic in many ways. Thompson also talked about some of his upcoming projects, his need to have “a real human quality to the line.” and why he wants to serialize his next graphic novel.

Alex Dueben: I’ve loved the book since it first came out, and I know lots of others who have, but a lot of readers who know you for Blankets or Habibi and might have missed it. What is Carnet de Voyage?

Craig Thompson: It’s a travelogue that I did very quickly in three months' time. It’s an unedited diary, so quite different from the other books where I labor over them for years. I disappear into my cave and really craft something specific. This was me off on a trip and keeping a diary and then publishing it pretty much unedited.

You have new pages in this new edition of the book talking about how quickly you made Carnet.

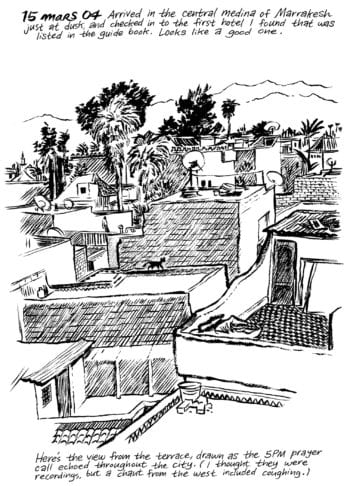

In the new edition there was talk of adding some extra pages. I decided to do this afterward focusing on the process of how the book came to be, because in some ways it does enhance the story a little and tell how spontaneous it was. Also what prompted it. I talk about that I was going through a difficult time in my life – a breakup – and like anybody I just wanted to get out of town. I had this plan to go to Europe for a few weeks and couch surf with friends. My European publishers found out that I was going to be around so it quickly exploded into this European book tour, which wasn’t my initial intention. Now I was on this book tour and I added three weeks to be by myself in Morroco and that’s documented in the book. Part of that was I had just started work on Habibi so I thought it would be good to spend some time in an Islamic country. Otherwise it was carving out that space for myself within the midst of a book tour.

As the trip got longer and longer – it was three and a half months – I started to get this anxiety about not being productive. Drawing and making comics grounds me and I knew that I would spiral off into neurotic despair if I didn’t have a project. I thought I’ll do a diary comic like I’ve seen other cartoonists do. At that time I was influenced by a lot of French cartoonists like Lewis Trondheim and Joann Sfar, so I thought I’ll do a daily comic and it will give me a task. I mentioned it to my publisher at the time, Brett Warnock at Top Shelf Productions, and said is that something we could publish down the road? Because that would be a cool book, like those L’Association books. Brett said, better yet, let’s have it in print this summer, which means it has to go to press while you’re on your trip. That’s what made it so much crazier.

You also mention that the book covers only about two-thirds of your trip because you had to send it to the printer while you were still on your trip.

You also mention that the book covers only about two-thirds of your trip because you had to send it to the printer while you were still on your trip.

There was another month of the book tour travel which isn’t documented but that’s probably for the best because at a certain point it gets a little monotonous just doing book signings. Even if you’re in new exotic places. In a way it was a natural ending point for the story.

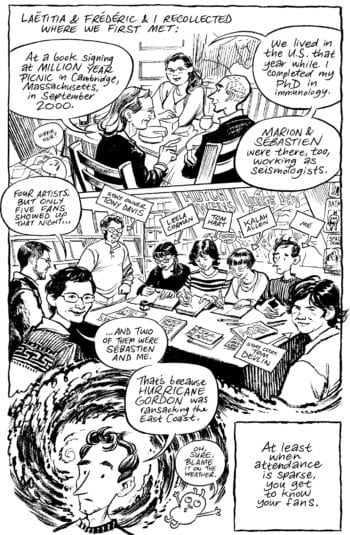

In the extra material you talk about a trip in 2001 where you met Lewis Trondheim who pushed you/inspired you to draw more.

Lewis and his wife Brigitte and their kids and a lot of the “supporting cast” in Carnet de Voyage were in my life on this previous trip three years prior. I met with the Trondheims and the Viviens and Sébastien and Marion, and some other cartoonists, too. That was one of my first big French trips in 2001. I went to my first Angoulême festival and I teamed up with Tom Hart and Leela Corman. That trip I went trying to find a European publisher and I had to see what the Angoulême festival is all about. As happens to many American cartoonists when they go to France for the first time, one they’re overwhelmed by the attention that comics get from a general public there, and two they’re overwhelmed by the virtuosity of French cartoonists. At book signings they do these elaborate drawings in every book as opposed to just a signature. They’re drawing all the time and they have this weird joie de vivre of drawing which American cartoonists don’t. American cartoonists are more neurotic about it. Then you go to France and everywhere you go someone is pouring a glass of wine and whipping out sketches like it’s nothing. I spent time with the Trondheims then and I remember Lewis telling me that he spends only two hours a day working and the rest of his day is play. And he’s one of the most prolific cartoonists in France! Or he was at that time. There’s something about the rhythm that he’s created in his work and personal life where he can get his work done in two hours almost off the cuff. The rest of the day he’s still sketching and absorbing things and observing things, but it’s not work for him. He treats it like play. So work is whatever comics pages he does that are going to be published. At the time he was publishing pretty much everything he did, so all the sketches had a home somewhere.

At that time what was your habit of keeping a sketchbook or a journal?

I think I was pretty good about it then. Before I did comics my modes of expression were letter writing and keeping a sketchbook. I did that since I was a teen. Like a lot of cartoonists I lost the habit of because you get into more of a productivity, this is my job sort of zone. You’re not keeping a sketchbook for fun and for play anymore. But at that time, when I was working on Blankets, I was trying to draw more from life. That original France trip in 2001 was right in the middle of working on Blankets so I was trying to discipline myself to draw anywhere. I guess that’s reflected in Carnet de Voyage. I was pushing myself because I came from that cartooning tradition of just drawing goofy cartoon characters from my imagination. I always had art teachers growing up who criticized me for never drawing from life; I just drew cartoons. Once I was in my twenties I was dabbling in that for the first time and trying to learn how to draw from life. And tapping the pleasure of that, too. It’s nice to get out of your own head. That’s a big moral from Carnet de Voyage. When I work on my graphic novels I’m isolated in my studio all alone and really sweating over everything in isolation, but Carnet de Voyage really got me out of my comfort zone and I was just drawing everywhere. I’d be drawing on trains and planes and on camelback while adventuring through the Sahara desert. I was also interacting with people and it wasn’t just that isolation.

As someone who has been on camelback a few times, being able to draw on the back of one is the most impressive thing in the book.

As someone who has been on camelback a few times, being able to draw on the back of one is the most impressive thing in the book.

[laughs]

In the afterward you talk about feeling self-conscious about how you come off in Carnet, which is you unfiltered and in your head, whereas your books are outside of yourself. Though Carnet is how you were in the world and to make the graphic novels, you have to be isolated.

It is, like I said, a diary. It’s much closer to unabashed intimacy and cringe worthy personal thoughts. I talk about how I was young. I was 28 but I was a very young 28. I hadn’t really traveled. I never really grew up traveling. I envy that naive state I was in then because everything was new and dazzling to me. I also cringe at it, too. My world consciousness was very limited at that age. That’s both a drawback and a perk, a strength and a weakness.

Making Carnet after Blankets, and especially looking back, how do you think that you appear here versus Blankets?

There is a continuation happening. Blankets is one step more naive and sheltered, being about my small town Wisconsin teenage-hood and childhood self. This is more about the process that came after of discovering the world. It’s a lot about first devastating breakups, too. Going back and rereading the book fourteen years after it was originally published, that’s probably the strongest emotional thread to me. This is about that first really big breakup. There’s some of that in Blankets, too, but this is the next relationship. The relationship that’s more serious and adult. we were together for eight years and lived together, so it’s that first young adult domestic relationship. It’s almost the first divorce in your life..

I was reminded of that famous Emerson quotation, “our moods do not believe in each other” when thinking about the “you” in Blankets and Carnet.

That’s the weird thing about all my books, but it’s also the thing that I’m grateful for. They are these snapshots of moments in my life. I could never write a book like Blankets now. I could never write a book like Carnet de Voyage now. They’re these great bookmarks of who I was. I like that. This doesn’t feel like when I find an old diary of mine that’s totally shameful and I want to destroy them. [laughs] Something about the act of drawing at the same time made it much more palatable and makes me grateful that I actually published it. This is a book that for a long time I was most happy with. Maybe because I knew it was raw and unfiltered and I hadn’t overworked it and over-labored over everything. I was really engaged in a weird way with the world rather than my neurotic isolation. I did this book in three months. I want to work like this all the time, really off the cuff.

You mentioned getting out of the practice of keeping a sketchbook, or drawing without purpose. What is your practice like now?

You mentioned getting out of the practice of keeping a sketchbook, or drawing without purpose. What is your practice like now?

I’ve gotten better about it again. Usually the time when I’m having the most fun with sketchbooks is after I finish a big project. I have a couple months where all I was really making myself do is work in sketchbooks every day. That’s the closest experience to drawing as a kid, just trying to find the things that are fun for me to draw. That goes away once you latch onto a project. Here’s a good idea and I want to pursue that, and then your sketchbooks start becoming more monogamous to that idea. Last year I did a lot of morning pages. I’ve never read Julia Cameron’s book but a lot of my writer friends endorse this idea of morning pages. You wake up in the morning and go straight to a blank piece of paper and just vomit out the noise in your head and don’t worry about anybody seeing it. The idea is if you can get that noise and clutter out, it’s like a meditation and then you can get to the quiet space to create. I was doing a lot of that last year and a lot of it was sketchbooks. I found it useful. I don’t think anybody will ever see those sketchbooks. [laughs] But ideas come out of that. I also try to do life drawing. I have a friend I’ve been doing figure drawing with for almost twenty years now. That’s something down the road I want to put out as a book, too. A collection of all these drawings and essays about that process. That’s a whole different story about having a creative relationship with a model – a platonic creative relationship.

Have you ever read the book Bento’s Sketchbook by John Berger?

No I haven’t.

It’s about Baruch Spinoza and it’s about the act of drawing and what it means. Berger compares drawing to riding a motorcycle at one point, that you pilot a bike with your eyes and then your body responds.

That’s great.

He had this one line passage that I wanted to read and get your response to: “The lines of a sign are uniform and regular: the lines of a drawing are harassed and tense. Somebody making signs repeats a habitual gesture. Somebody making a drawing is alone in the infinitely extensive.”

That’s perfect. That kind of drawing, drawing from life, is a meditation. If you’re really present with everything but with your breath with the moment with whatever is in front of you and with the process. It’s pleasurable. I can’t say that drawing comics is pleasurable. At least at this point. I know that Chris Ware and a lot of people have talked about the drawings in comics aren’t really drawings. They’re symbols. Cartooning is symbols. It’s a shorthand. A typography. It does take some of the pleasure out of drawing, but when you can get back to looking at what’s in front of you and being present with that, it’s really a transcendental bit where you get out of your own consciousness. That sounds really hippy dippy when I describe it that way. It can be frustrating too because you’re looking at what’s in front of you and your drawing doesn’t match that. [laughs] But if you’re not thinking about the drawing and the paper and you’re just being present with what’s in front of you, that feels really good.

You mentioned that many French cartoonists have a different approach to drawing and making art. Is that because they work differently? Do you react this way because of what they make? Or do you think that because they have health care and don’t have to worry as much as we do that they’re able to work and think differently?

[laughs] It’s all those things. It’s health care and the government provides you with a stipend. Brecht Evans, the Belgian cartoonist, was telling me he’s never had a job in his whole life because he’s always gotten government funding ever since he was a teenager. Even Edmund Baudoin who I’ve been collaborating with said that if you claim that you’re an artist on your tax returns you get a stipend. That removes some stress from making art. Here we do obsess a lot more over how we’re going to pay the bills or how do we make our art mainstream or accessible so that we can make a living off our personal stuff. Then healthcare helps a lot, too. Also I think it’s cool to be an artist or a cartoonist in France. When you’re in elementary school all the kids think you’re the coolest, where most of the cartoonists I know in the US were harassed or bullied as children. There’s a shame and neurosis attached to cartooning.

You make a comment in the afterward about being over-saturated with images.

You make a comment in the afterward about being over-saturated with images.

That’s still a thing I wrestle with every single day. There’s too much media and we’re saturated with images. It takes away the motivation to add to the heap of a glut of media in every form. That feels different from the nineties when I got started in comics when it was still a pre-internet age. People talk about how hard it was to track down a certain album or something and how that hunt the difficulty of finding something gave it more value and pleasure. My generation of cartoonists was doing zines and minicomics and just mailing them to each other. There was such a thrill to that and it was such a small support group and it was very personal media. Now there’s just so much noise. Every day I question why I should add to that pollution. I talk about that in Carnet de Voyage too. That weird guilt about how with every page of comics you make there’s a tree being cut down. I don’t know the answer to that question. It’s this constant struggle. It does take a lot of time every day to give myself permission to make things.

Is there a chance that you’ll make another travelogue or sketchbook?

I would never do one this way again. Which was on a book tour, which is completely insane. [laughs] Now when I go on a book tour any free time I have is towards relaxing whether having drinks with the organizers or getting some sleep or exercising. The last thing I want to do when I’m done signing books is to draw more. I think that’s healthy. I need balance. I’ll never do one on a book tour again. There’s a Carnet de Voyage that I have been working on with Edmund Baudoin, the 75 year old French cartooning master. We spent two months traveling together making sketches and working on a book together. We spent a month in the South of France where he grew up and then we did a long road trip in the US through 15 states, driving from LA where I was living at the time, to Wisconsin where I grew up and then circling back. We have a couple hundred pages of sketches, but unlike Carnet de Voyage, neither of us were keeping a comics diary. We were sketching what we were seeing and so we’re still searching for the narrative. That would be a weird hybrid Carnet de Voyage. Because some of the work – maybe the majority of the work – is going to have to be done now after the fact. Because we didn’t produce a Carnet de Voyage in those two months of travel, we just produced a pile of sketches. They’re not a story. I’m dragging my butt on that but that’s one of the projects that’s in the mix of things I’m doing. I don’t want to give away other ideas, but it would be great to just go away on a trip for one to three months and make a book about that place and draw in real time. I just have to find the time to do that.

Mapping a narrative or creating connective tissue onto all the sketches turns it into a whole other kind of project.

Mapping a narrative or creating connective tissue onto all the sketches turns it into a whole other kind of project.

In a way it sounds great because it takes away all that stress and pressure of doing it in real time, but it also takes away some of the motivation. Suddenly you’re in a different moment and now it feels like all my other books because I’m crafting something by looking back on the past. I’m not being present. It takes away that pure-ness.

My editors and I were talking over e-mail about this and one said, why aren’t there more comics travelogues like this? Because we all know cartoonists who love your book. And the few comics travelogues I can think of are more polished and made after the fact. I don’t have a good answer but I would imagine rawness is one reason.

Yeah, I don’t have an answer for that either. It’s true what you said. I have a lot of cartoonist friends who have said, I don’t really care about your other works, but I love this book. Which I always take as a compliment and I kind of get it because I feel that way about other artists work. Some things are too polished or feel labored over. As a cartoonist that’s less inspiring to me than something really raw and grasping. I like seeing process a lot. I like the smaller, lesser works of a lot of cartoonists more than their opuses. But it’s a great question. I can’t think of a lot right now.

You mentioned those two books you’re at some stage with, but what are you working on now?

I am still secretive about it, but I’ll probably be ready to announce it this fall. I haven’t signed a contract yet, but the plan is to serialize it as a comic book. For the first time in my career. When I did Blankets I was really pushing against comic book store culture and collector mentality and serial comics. I was sick of the format of comic books. Now I’m sick of graphic novels and the pretension around them and the prohibitive cost and space they consume. We live in this era over-saturated with media and images and there’s something really pure about the 24-32 page comic book to me now. As I was struggling with how to structure this new book, I realized that I want to do it as a comic book. It’s still going to be a graphic novel but I want to use the constraint as the structure. I’m excited about comics as a medium again.

Blankets wasn’t the first big graphic novel I bought, but it might have been the first one I bought that hadn’t been serialized.

Blankets wasn’t the first big graphic novel I bought, but it might have been the first one I bought that hadn’t been serialized.

Strangely I think you’re right. I was stealing it from the French. Lewis Trondheim made a 500 page book and that was his first thing. He talked about how we was learning to draw through that process.

Is this going to be a shorter or longer book?

[laughs] Unfortunately it’s going to be another Blankets-Habibi. I resisted that for so long. I did not want it to be that and I was trying to figure out how I could cut it down. It wasn’t until I came upon the serialization idea that it started to feel more right for me. Every book I’m like, I want this to be 300 pages, I don’t want to make a 600 page book. Hopefully I can get this in the 300 page realm, but in spirit it’s a long one.

I just remember when we spoke about Habibi years ago, you thought it would be a shorter book after Blankets.

Yeah, I wanted it to be 250 pages.

So that keeps happening.

Yeah. It might still happen. But I hope that this serialization makes it more pleasurable for me. It means I can start having stuff out next year rather than disappearing for years and years again.

Anders Nilsen seems to be really enjoying serializing Tongues.

That’s a great example. I don’t know if I’m as bold as him, though, self-publishing. But his book is a good example of what I like reading these days. The new Crickets or Ganges or Tongues are much more exciting to me right now than graphic novels.

Just to end, what have you drawn today?

I’ve drawn thumbnails for the new book. I was working on writing earlier today because the new book is still very much in the writing/thumbnail process. I was getting stuck on the writing so I switched over to roughing out some pages and I got more engaged in the process and started to enjoy drawing. So many ideas come in the drawing process, which is why when I write my books I do really detailed thumbnails. I don’t type a script and then years or months later illustrate that. These days I’m using a mix of a lot of things so I will type out a script only because it’s helping to organize the doodles and the making of pages. I’m thumbnailing and typing and with this new book I’m trying to thumbnail it digitally. I’m planning to draw the book on paper but there’s some perks to digitally thumbnailing it because I can cut and paste things really easily and edit really easily. I think that’s saving me a little stress.

But you’re planning to draw the final comics with pen on paper?

That goes back to the pleasure of drawing. It’s much more pleasurable. Being at the computer just isn’t that fun, but the digital is really good for me as a step in the process. It’s always important for me to get back to having a real human quality to the line and that would get lost for me in the digital.