Edvard Munch, 1863–1944, was a zeitgeist conductor. Like Dostoyevsky before him, like Kafka after him, he was one of those somewhat hastily assembled humans—the skull plates not stapled down, the nerve endings dangling—who get chosen by the daemon of history to bear its message into the world.

Poor bastard. “You paint like a pig, Edvard!” yelled a young realist named Gustav Wentzel, getting in Munch’s face at an 1886 exhibition in Kristiania (now Oslo) that featured his painting The Sick Child. “Shame on you.” Munch, at the time, was penniless. His best friends were nihilists. Also alchemists, sadists, diabolists, absinthe fiends, and the occasional haunted dramatist. Ibsen came to his 1895 exhibition, the one that sparked a public debate about Munch’s sanity, and growlingly counseled him: “It will be with you as it was with me. The more enemies you have, the more friends you will have.” Strindberg, very mad, was a fellow paranoiac: “As regards Munch, who is now my enemy,” he wrote to his editor, “I am certain he will not miss the opportunity to stab me with a poisoned knife.” Years later, when Munch was painting on the beach and a gust of wind upended his easel, he blamed Strindberg.

Alienation, God-death, the self as destabilized center of experience—this was the daemon’s message. The full harrowing gospel of modernity. It lived inside Munch, forcing its way along his fibers and blazing out of his doomy Scandinavian eye sockets. It gave him breakdowns and a massive thirst for alcohol. It made him strangely attractive to women. It hospitalized him, several times. He starved, he raved, he was vilified, and—being a great artist—he understood exactly what was happening. “If only one could be the body through which today’s thoughts and feelings flow,” he wrote to a friend. “To succumb as a person, yet survive as an individual entity, that is the ideal.”

And what does one paint, after the person has succumbed? What does one seek to represent? Not the merely external, the inert and boring there. And not the fluttering optical field of the impressionists, whose advances he had absorbed while living in Paris. Munch wanted to go past the eyes, further into the head. He was after the deepest action of the outside upon the inside, the pressure of the universe upon the mind. This, for him, was realism. This is how you get to his smash hit, his psychic world-statement: The Scream. The foregrounded figure on the walkway, the light-bulb-shaped head, the fishy hands, the bands of sound warping the evening sky, the powerless cartoon face stretched in terror—all that’s left of the human is a kind of flipped switch, an opened channel to the vibration of reality. Which is overwhelming. “I heard a huge extraordinary scream pass through nature,” he wrote later.

“Trembling Earth,” the glorious new exhibition of Munch’s work at the Clark Art Institute, in Williamstown, Massachusetts, is not exactly a rebuttal to The Scream, but it so amplifies our understanding of the artist as to constitute, almost, a counternarrative. It’s a revelation. Mystical experiences can be negative, as many of Munch’s certainly were: They can show you how it feels to fall out of the hands of the Holy Spirit. But the deeper you go, the higher you fly, as the Beatles said. Here the scream that passes through nature carries a note of ecstasy.

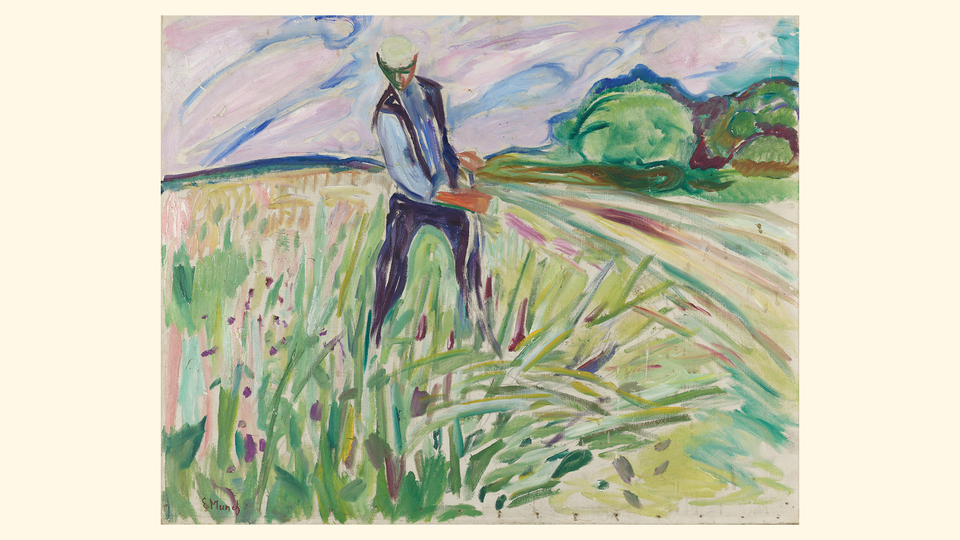

The paintings at the Clark are presences—generous ones. They radiate, shedding a supernatural warmth. As you enter the gallery, you meet The Yellow Log : felled tree trunks stacked in a snowy forest. The trunk at the top of the stack launches right out of the picture and off the wall, as laser-straight as the handrail in The Scream. But it glows gorgeously, this tree trunk; it shines at you like a cauterized sunbeam, its cut end a brilliant disc of white gold. In The Haymaker, the landscape pours forward on a wheat-colored curve, a rush or spill of summery splendor that threatens to carry off the figure scything grass in the foreground—but the haymaker, via the flex of his braced legs and the torque in his body as he calmly swings the scythe, redirects the current, keeps it flowing: He’s at home in this world. And those rows of smoldering blue-green cabbages in Cabbage Field—are they streaming toward the horizon, narrowing to an omega point/flash of nullity, or are they streaming out of it, as if to embrace us? (Embraced by cabbages: That’s how this show will make you feel.)

Melancholic Munch, mad moody maimed-by-modernity Munch, is well represented in “Trembling Earth.” There are creepy scenes in glades, empty faces, heads in hands, bleak semi-allegorical figures gazing at the sea, apple trees boiling like toxic soup, and a black-and-white lithograph of The Scream itself. But these images are contrapuntal to the theme. One wall away from the Scream lithograph is The Sun, from 1910—a dazzlement of rays and light pellets flung off an ocean sunrise. Behind all of the brightness, you can even see the vague skull shape of the Scream head, as if the sun itself is a blast from its third eye.

Munch had his own sort of weirdo metaphysic, an intuitive and crank-scientific faith in the great self-renewing ferment of life, the mulching of souls, the crystals, etc., and as he got older he would explore the implications of this in images of near-Blakean luminosity. Male and female essences; volcanoes of yearning beings. “The earth loved the air,” reads one crayon-on-paper text from a 1930 album called The Tree of Knowledge.

Like all genuine craftsmen, Munch respected labor. Forestry. Harvesting. The working of the land. In Digging Men With Horse and Cart, from 1920, the men are bent double over their shovels while the white horse standing between the shafts is an almost transparent wreath of energies and bunched muscles. The horse—for which Munch’s horse Rousseau may have been the model—nods at the digging men, conferring a blessing.

About his own work Munch was wonderfully un-precious: Although he loved his paintings and referred to them as his “children,” he would heap them carelessly, trip over them, drip on them, absent-mindedly bash them around, or leave them outside to take their chances in the elements. (He was semiserious about this: The process of weathering his paintings, exposing them, he called the hestekur—the horse cure.) A visitor to a later Munchian studio, inquiring why a certain canvas had a large hole in the bottom corner, was startled to hear that one of Munch’s dogs had run right through it.

“His paintings, landscapes as well as representations of human beings are suffused by deep passion.” That’s Goebbels. Hitler was less of a fan, and in 1937 dozens of Munch’s paintings were caught up in the Nazi sweep of “degenerate art.” Munch’s last years were spent under German occupation, at his country seat in Ekely, Norway. On the day of his death, age 80, he was reading, for the umpteenth time, his copy of Dostoyevsky’s The Devils.

The Scream will live forever. It’s a cave painting on the inner wall of the human skull. And Munch himself heard the scream, no doubt about that: It ran through his being. But there’s a paradox. To produce an image like that, an image of such cosmic vulnerability, you need great strength. You can’t collapse, or not totally. You need to be extra durable. You need to be able to handle it. And Munch, for all his infirmities, could handle it. He had a secret health, a secret hardiness, and the show at the Clark puts us in touch with its source.

This article appears in the September 2023 print edition with the headline “A Sunnier Edvard Munch.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.