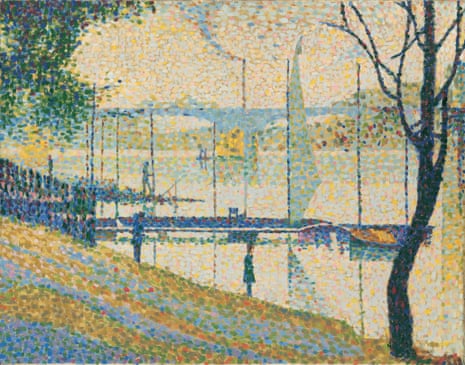

Looking from Bridget Riley’s mind-boggling 1960s paintings to Georges Seurat’s calm river scene in The Bridge at Courbevoie, painted in 1886-7, is not only thought-provoking but puts your eyes to the test. After looking at her pounding psychedelic art, I could barely see the Seurat. I had to let my eyes readjust before I could properly make out its misfits and fishermen on the banks of the Seine, let alone appreciate the play of tiny dots that creates its pointillist shimmer.

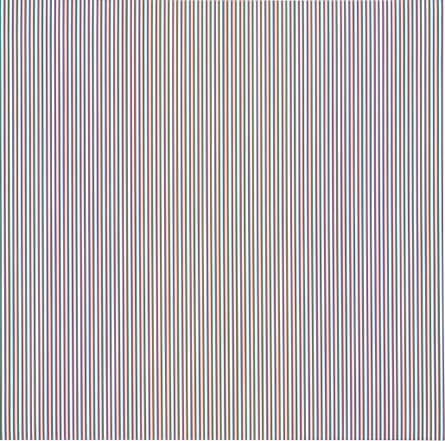

Riley is the most revolutionary British painter of modern times. Her paintings don’t merely hang on the wall: they warp and pulsate, sucking your imagination into unreal worlds of impossible depth and hallucinatory colour. What was she on when she came up with her dangerous vision?

It turns out she was simply looking at a painting by Seurat, the postimpressionist who created a new way of seeing the world as a field of coloured dots. The Courtauld Gallery owns The Bridge at Courbevoie, one of Seurat’s still, silent masterpieces, and in 1959 the young Riley set out to make a copy of it. It still hangs in her studio, which shows how crucial Seurat, who died in 1891 in his early 30s, has remained to her thinking about art. Riley has also called her copy – which she has lent to this fascinating little exhibition – a “tool”, revealing what her and Seurat have in common: they both practice art as an optical science.

This intense exhibition – just one room hung with stunning art – is an antidote to all the loose talk these days about contemporary art interacting with the “masters”. From shows of Rubens or Botticelli that are top-loaded with contemporary art to the Frieze Masters art fair, the art world likes to claim continuity and connection between old and new. All too often, such claims are insubstantial. But Riley really did forge her optical style by studying Seurat, so this is a genuine encounter between old and new.

Then again, Riley is no ordinary artist: she is truly intelligent and free from sentimental egotism about the artist’s role. In 1959, male painters like Bacon and De Kooning were spattering oils about and airily being compared with Velázquez. Yet there was young Riley, then 28, putting herself through school, modest and free from macho vanity. Working from an image in a book, she imitated Seurat’s Bridge on a bigger scale, with more fulsome dots, as she tried to understand how his pointillist method exploits the power of complementary colours. She started painting her own pointillist landscapes. (Her picture of the sun-filled hills of Tuscany could easily pass for a postimpressionist original – it’s a good thing she never went into faking.) From there she created the abstract masterpiece Tremor, whose convulsive beauty takes apart your senses and rearranges your neurons.

My mind is blown, but stimulated as well, for Riley has something else in common with Seurat and the other great artists of late 19th-century France besides an interest in the science of colour: a joy for life. We so easily mistake misery for seriousness – images of death and despair are hailed as profound. But in Seurat’s age, the sheer pleasure of the eye, the ecstasy of seeing, was radical. Colour and light were beams of hope. Riley also creates visual pleasure. Her assault on stale reality is to create a utopian explosion of joy.

When your eyes finally adjust, the delirium of her work casts new light on Seurat. He suddenly looks very 1960s himself. A smokestack in the distance in The Bridge at Courbevoie turns out, on closer inspection, to be a column of sparkling jewels out of which a vapour of emerald dust floats upward.

Beside the Seurat hangs Riley’s painting Vapour, whose bands of colour seem restrained until you realise they are melding in your mind to create the illusion of a lime-green mist floating in space.

A few great paintings of this calibre, so intelligently compared and spaciously displayed, are worth a dozen ill-conceived blockbusters. Georges Seurat was a genius, and so is Bridget Riley. Together, they set the air alight.

- Bridget Riley: Learning from Seurat is at Courtauld Gallery, London, from 17 September to 17 January 2016.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion