As Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night Over the Rhône goes on show at Tate Britain, it is, in one sense, coming home. This might sound like wishful thinking. For the past half century the painting has hung in Paris, and its singing Mediterranean colours, which the artist himself described as “aquamarine”, “royal blue” and “russet gold”, bear little resemblance to the murky half-tints of the Thames, which runs past Tate Britain’s Millbank site. Yet its spring exhibition, Van Gogh and Britain, is organised on the principle that the foundations of the Dutchman’s art, both his eye and his intellect, were laid not in the south of France, nor in the misty light of the Low Countries, but in London, where he spent three life-defining years (1873-76) as a young man.

A case in point: if you look beyond the hallucinogenic brilliance of Starry Night Over the Rhône, which Van Gogh painted in 1888, two years before his death, you will notice a family resemblance to a small black and white engraving that he first encountered more than a decade earlier, during his London stay. Gustave Doré’s Evening on the Thames shows London from Westminster Bridge, a view Van Gogh knew intimately from his commute between his suburban lodgings and the Covent Garden office where he worked as a clerk. It wasn’t the pomp of the neo-gothic Houses of Parliament that drew Van Gogh to Doré’s image so much as the regular pattern made by the gaslights as they flared across the river. Fifteen years later he would transpose this jolt of modernity to Starry Night Over the Rhône, a view of Arles in which new-fangled streetlamps compete with exploding stars to light up the sky.

Van Gogh’s connections to British culture go even deeper. Carol Jacobi, the lead curator of the Tate exhibition, explains that the Dutchman was “an intensely literary artist, and the books that he read during his time in London were as important to his later development as the images he encountered in the city”. Van Gogh’s letters home to his family are crammed with references to classics that he had devoured during his time in Britain, including John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. His favourite author remained Charles Dickens, closely followed by George Eliot. Sharp-eyed art historians have pointed out that the night sky in the Rhône painting is a direct quotation from a scene in Dickens’s Hard Times, in which the secondary hero, Stephen Blackpool, gazes at a star as he lies contemplating his difficult life and imminent death.

Van Gogh loved Dickens and Eliot for the way they took the everyday details of modest lives and elevated them into something luminous. Here was social realism, in all its unloveliness, transformed into a kind of moral grandeur. A few years later, and on his way to becoming the artist who would invest old shoes, ragged sunflowers and potato-eating peasants with powerful feeling, Van Gogh wrote to his brother: “My whole life is aimed at making the things from everyday life that Dickens describes and these artists draw.”

The artists he was referring to were not the old masters, but rather the makers of a new kind of imagery in which his employers, the art dealers Goupil & Co, traded. At the time of Van Gogh’s arrival in 1873, London was establishing itself as the world capital of the graphic arts, fed by a thriving literary scene, modern production methods and a huge international market. Along with Doré, artists such as Luke Fildes and Hubert von Herkomer used bold contrasts of light and shade to convey the textures of life in the world’s largest metropolis. Instead of placid Madonnas and glittering generals, they drew men and women waiting for the pub to open, street-cleaners wearily pushing their carts, and Newgate prisoners condemned to walk in a perpetual circle. By the time of his death Van Gogh had collected 2,000 of these prints and engravings, popularly known as “black and whites”.

The quality that drew him to this new democratic art was the same impulse that propelled him towards the novels of Dickens and Eliot. Both seemed to offer an encounter with a way of life that was more authentic than his own, with which he was becoming increasingly disenchanted. Wearing a top hat and taking the tube to work when it rained had been novel and exciting at first, but now it seemed increasingly pointless, especially when confronted by the constant sight of poverty and desperation on the city streets. In his reading of the English literary classics Van Gogh was particularly drawn to working-class heroes who, despite having the intellectual resources to leverage themselves into the petit bourgeoisie, chose instead to remain among their own people. Stephen Blackpool from Hard Times is one such character, and so is the eponymous hero of Eliot’s most political novel, Felix Holt, the Radical. As a pastor’s son, Van Gogh had always been aware of the plight of the neglected, the old, the suffering and the poor. Now, though, he was planning to give up the clerking life and take his place permanently among the city’s outcasts, as a minister or a missionary. His eye had been particularly caught by Whitechapel, which he identified in a letter to his brother Theo as “that extremely poor area which you’ll have read about in Dickens”.

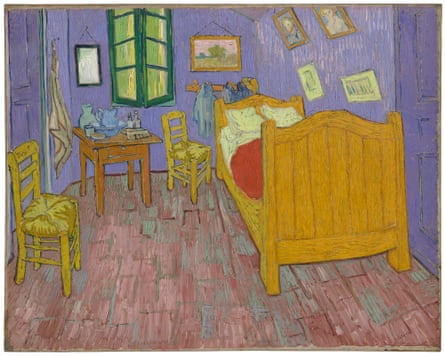

It was in the final months of his life during which his mental health declined and his art soared, that these early London associations flooded back most insistently into Van Gogh’s work. Take The Bedroom, the famous rendition of his room at the “Yellow House” in Arles where he lived for a short, tumultuous time with Paul Gauguin. In 1889, and working on a version of the painting for his mother, he wrote to his sister Wilhelmina from the Saint Paul asylum at Saint-Rémy: “You’ll probably find the interior the ugliest, an empty bedroom with a wooden bed and two chairs ... I wanted to arrive at an effect of simplicity as described in Felix Holt.” Here was a reference to Eliot’s working-class hero who, despite the temptation to rise into the middle class, chooses an existence of material simplicity and moral rigour.

Van Gogh’s great innovation is to take a humdrum scene – the bedroom of a poor working-class man which might at first seem to demand monochrome – and flood it with gorgeous colour. In his reimagining of Holt’s bedroom, which is also his own, the walls are lilac, the counterpane a singing red and everything is on a hallucinogenic slant. Yet this is not the work of a deeply troubled, purely instinctive painter, pulling images randomly out of his teeming unconscious. What we have here is the work of a supremely self-conscious and disciplined artist who has chosen to synthesise the visual and textual references that he gathered over a decade earlier in a city of smoky half-tints and deeply felt moral conscience.