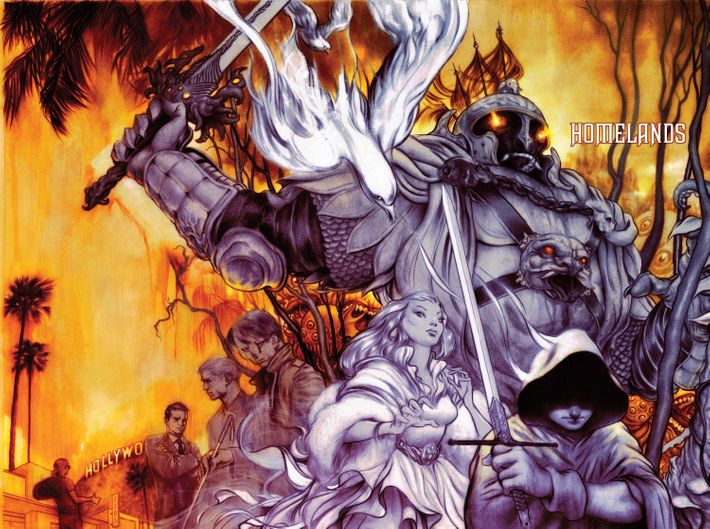

In 2002, writer Bill Willingham began Fables as a comics series with a simple premise: to reimagine fairy-tale characters such as Snow White, Cinderella, and the like by looking at their stories and asking, “What happened next?” That premise in less skilled hands would have proven flimsy, but Willingham has built a remarkable and sprawling comics epic out of it — an epic that is, sadly, coming to a close. After 13 years, 150 issues, and multiple spinoffs, the long-running, hugely acclaimed Fables comes to an end this week in an enormous 150-page finale.

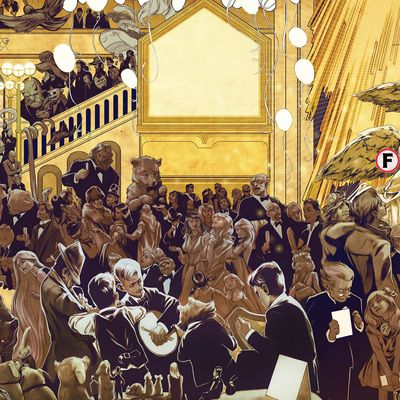

The story has centered around a version of New York City not unlike our own, but containing a hidden realm called Fabletown. There the characters we know from childhood were collected and interwoven in what would become a massive saga of fairy-tale characters living secret lives among us. Far from merely going for cheap laughs about princesses and wizards having sex, the story has pulled in readers with an action-packed narrative and genuine insights about human nature. The series — published by DC Entertainment imprint Vertigo — has been nominated for numerous awards and collected 14 Eisner Awards (the comics industry’s top honor), including a Best Writer award for Willingham himself in 2009. Not only is Fables’ longevity rare, its influence has rippled beyond comics to impact popular culture at large.

For fans who were loyal to the series from the beginning, the last issue of Fables ushers in the era of nostalgia that follows the last page of a favorite book. They’re not alone: Willingham is also in a wistful and melancholy mood. We caught up with him to talk about the secret origins of Fables, TV shows like Once Upon a Time and Grimm, drawing inspiration from The Shield, and how he’s never felt totally satisfied with the series.

When you were developing Fables, which elements of the story came first?

I think it was the setting, because I like the idea of secret societies. The idea that there’s a community of fill-in-the-blank living amongst us, under our noses, and we haven’t a clue. The fairy-tale characters came after the fact, when I started asking, Well, if it’s a community of something, what are they? Vampires were done to death, and I was considering mythological characters for a while and decided they were still a little well-used. I finally hit on fairy tales and thought, They’ve been done, too, but not recently, and perhaps not very well recently. So I kind of backed into it.

After your pitch was accepted, were you left alone to write it, or were there unanticipated changes the publisher requested?

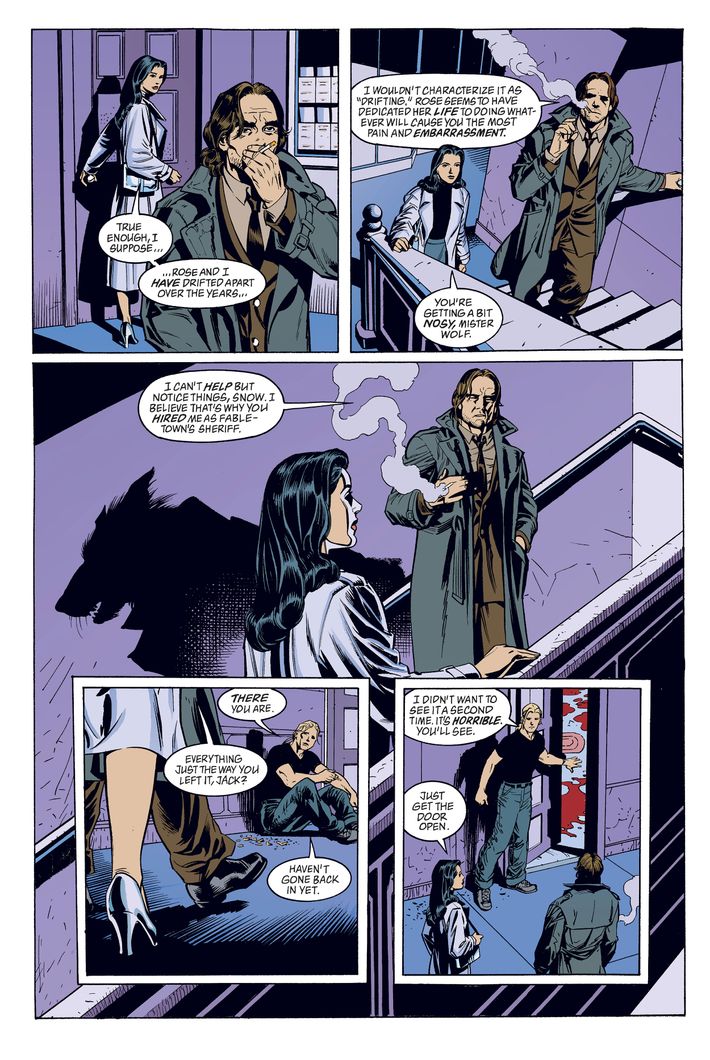

When I made the pitch, there were several story arcs planned, one of which was the murder mystery of Rose Red — which turned out not to be a murder-mystery — and the only thing Karen Berger, the head of Vertigo, asked was that I put that story line first. Her concern, I think, was that she wanted to make sure people knew this was not fairy tales out in the woods with people prancing around with unicorns and butterfly wings, because Vertigo was not a prancing-around-in-the-woods-with-unicorns kind of imprint. She wanted gritty and urban, and the murder-mystery in New York seemed to be the most gritty and urban of the three or four story arcs at the time. Other than that, they said to go ahead and start writing them. This was the quickest acceptance I’d ever had from DC or Vertigo. From the time I submitted it to the time they said, “Go ahead,” it was about a week.

Were there any specific themes you wanted to highlight?

Not really. I wanted the characters to be new and interesting. I wanted it to seem like lots and lots of stuff had happened to the characters since the last time we saw them back in their original stories. I’d seen a few things revisiting fairy tales, and most of them solved the problem by picking up immediately, time-wise, from where the original fairy tale left off. Others had them frozen in time: You saw this person way back when, and now we’re gonna do more even though it’s modern times, and apparently they haven’t done a damn thing in the interim. They’re still the same personality, the same basic people they were.

I thought, if centuries or millennia had passed since we saw these people, we’d best have a lot of things that have occurred. That’s how a big villain, the Big Bad Wolf, became a hero, and then we kind of hinted and filled in how that happened. Snow White became kind of a hardass with a giant stick up her butt, because for the last thousand years or so, it’s filling in the fact that everyone she’s known or loved has betrayed her in some way, so she’s going to rely solely on herself. But I don’t want to say their original story didn’t happen. The predicate was, “All the old stories happened exactly as we have heard they happened, but here’s how it’s changed.”

How have you felt about Fables’ role in influencing popular folklore-based stories such as Grimm and Once Upon a Time? Did seeing those shows give you a sense of pride?

I suppose so. There’s some pride of authorship or pride of re-authorship. I would have to say that it’s pretty likely that Fables influenced some of the stuff that exploded out into pop culture recently. That said, there’s a danger to suspecting that you’ve influenced them — the next step is taking credit for them.

In the waning years of his career ,my love for Isaac Asimov was colored by the fact that he went around taking credit for every story about robots written by anyone — and specifically because they either adhered to his Three Laws of Robotics or specifically ignored them. It was a little unseemly. So I try to make sure that’s not the case. I’m not the author of any of that stuff, nor is it a ripoff. That’s their use of the same characters owned by everyone. I don’t know if pride is the right word, but some realization that I may have had some impact on the pop culture at large — that’s kind of nice to know. Or suspect, anyway.

How would you describe what success looks like for you with this series? And has that definition changed over the years?

I don’t know if I agree that it was amazingly successful. I’m still, in my heart and mind, hoping Fables is gonna catch on someday. Success is an upward slope. No matter where you are on that slope, you’re not saying, Okay, this is good enough. Whatever hardwiring we have from our caveman days requires that the struggle always continues and you always want something more.

That said, since this was the first book in a long time where, once it got under way, I never had to worry where my next meal was coming from, there’s a certain amount of success there. Success in readers was kind of a new thing for me. I had a little of that early on in my career, and then almost nothing in the interim years. Success with readers was always, Well, this is a surprise to me, and it’s very nice and I wish there were more. And I think that’s always the case. You sell thousands, you want to sell millions; you sell millions, you want to sell billions.

Was there ever any thought of continuing Fables for as long as it was selling? Or did you always have an endpoint in mind?

My initial conviction, once it looked like the thing had legs and that it would go for a while, was that I wanted Fables to run for one more issue than [Dave Sim’s comic] Cerebus. That was, at 300 issues, the longest-running series by a single creative team, so I would’ve liked to do 301 just to do one better. So, by that definition, we only got to the halfway point. But what really determined it was that as we approached this final story line, it began to feel like the final story line. It felt appropriate.

And when it comes to the final story line, you get to that weight of wrapping it up “right,” whatever that means for you. Were there guidelines, whether from other comics or television or movies, that guided your approach to ending it?

You hit the nail on the head there. There was a lot of concern that the ending felt like it was the only ending they could have had. The Shield is a good example. The Shield had to end with viewers frustrated — frustrated in the sense that Mackey gets away with it, which seemed impossible, but at the cost of every person around him. He had to lose everything to do it. The implication, of course, is that he destroyed himself in the process. He did it not in a blaze-of-glory gun-battle way, he did it being pecked to death by bureaucracy so he’s steadily miserable. That was a fine ending. If the readers look at the finale of Fables and say, “Okay, I didn’t want it to end, but since it did, this is wonderful,” that would be the perfect win. If there’s a lot of, “How dare they not address this or that,” then it’s going to be a little less than satisfying.

What advice would you pay forward to any writers who are planning a series, much in the way you were over a decade ago?

Spend all your ideas as fast as you get them. Don’t sit on good ideas under the impression that those are the last ones you’ll ever have. It’s been my experience that the faster you spend them, the faster whatever good-idea bucket you have fills up with more of them. So spend the gold as quickly as it comes in. Every writer should be an avid spender. Do not sit on your treasure.