LILIES - RHS Lily Group

LILIES - RHS Lily Group

LILIES - RHS Lily Group

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>LILIES</strong><br />

and Related Plants<br />

75 TH ANNIVERSARY ISSUE

<strong>LILIES</strong><br />

and Related Plants<br />

2007-2008<br />

75 TH ANNIVERSARY ISSUE

Lilies and Related Plants<br />

Published by The Royal Horticultural Society <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong><br />

80 Vincent Square, London SW1P 2PE, UK<br />

www.rhslilygroup.org<br />

Copyright © 2007 <strong>RHS</strong> <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong><br />

Text and illustration copyright © individual authors.<br />

ISBN 978-1-902896-84-7<br />

No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form, by any<br />

means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any<br />

information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission of<br />

the editor and author.<br />

Editor: Caroline Boisset<br />

St Olaves, 19 Woolley Street, Bradford-on-Avon, Wiltshire. BA15 1AD, UK<br />

Tel: +44 (0)1225 864808 e-mail: carolineboisset@btinternet.com<br />

Subscriptions and membership:<br />

Rose Voelcker, Langique, 32380 St Léonard, France<br />

Tel: ++(0)5 62 66 43 76 email: rvlangique@wanadoo.fr<br />

Typeset in Garamond and Frutiger by Rob Kirkham and<br />

printed at Four Way Print Limited, Launceston, Cornwall<br />

Opinions expressed by authors are not specifically<br />

endorsed by the <strong>RHS</strong> <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong>.<br />

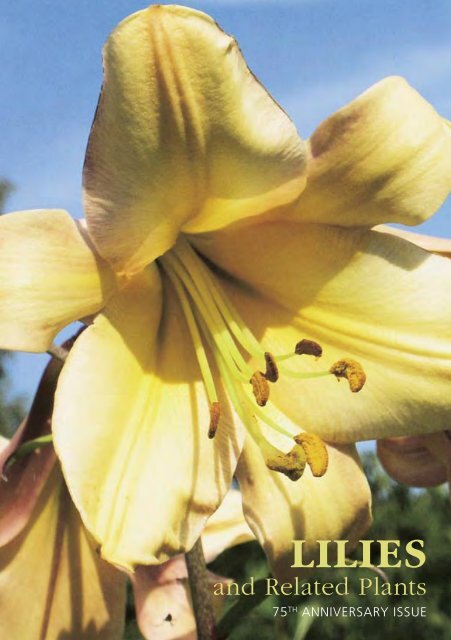

Front cover: Lilium ‘Apfelblüte’ is one of Heinz Boehm’s hybrids. He always<br />

wanted to breed a red trumpet... (see pp. 87-90)<br />

Back cover: Lilium lankongense was one of the key species used by<br />

Dr Christopher North in his breeding programme (see pp. 47-52).<br />

Here the species is growing in Pontus Wallstén’s parents’ garden<br />

in Switzerland (see pp. 58-67)<br />

Half title: Erythronium californicum showing the white anthers and<br />

slender filaments in Trinity County, California (see pp. 80-86)<br />

Committee members page:<br />

Lilium martagon growing on Baker’s Hill near The Wakes in<br />

Selborne, Hampshire where Gilbert White gardened.<br />

(see pp. 98-103)

<strong>LILIES</strong><br />

and Related Plants<br />

2007-2008<br />

75 TH ANNIVERSARY ISSUE<br />

Editor<br />

Caroline Boisset<br />

The Royal Horticultural Society<br />

LILY GROUP

Royal<br />

Horticultural Society<br />

<strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong><br />

HONORARY OFFICERS 2007<br />

Chair Dr Pat Huff<br />

+44 (0)20 7402 1401<br />

email: pat.huff@mbmc-crawfordstreet.co.uk<br />

Secretary Dr Clare Thornton-Wood<br />

Tel: +44 (0)1403 753077<br />

email: c.thortonwood@btinternet.com<br />

Treasurer D.S. Colin Pope<br />

email: ColinPope@AL86HW.fsnet.co.uk<br />

Membership Secretary Rose Voelcker<br />

Tel: + 33 (0)5 62 66 43 76<br />

email: rvlanjique@wanadoo.fr<br />

Seed Distribution Alan Hooker<br />

Tel: +44 (0) 20 8554 2414<br />

email: alan.h2@tiscali.co.uk<br />

Yearbook Editor Caroline Boisset<br />

email: carolineboisset@btinternet.com<br />

Newsletter Editor Vacant<br />

Web Producer Jeff Coe<br />

email: webmaster@rhslilygroup.org<br />

Committee Alisdair Aird<br />

Chris Brickell CBE VMH<br />

Harris Howland<br />

Richard Hyde<br />

Nigel Rowland<br />

Dr Nuala Sterling CBE FRCP<br />

Tim Whiteley OBE VMM<br />

www.rhslilygroup.org

Contents<br />

Notes on Authors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1-2<br />

From the Chairman<br />

by Pat Huff . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3-4<br />

Mrs D.A. Martyn Simmons (1912-2004)<br />

by Richard Dadd . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5-8<br />

The conservation of wild lily populations in Japan<br />

by Katsuro Arakawa . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9-14<br />

Derek B. Fox (1926-2007)<br />

by Roy Carter . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15-17<br />

The lilies of Greece<br />

by Arne Strid. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18-26<br />

Sir Peter Smithers (1913-2006)<br />

by Gian Lupo Osti . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26-27<br />

A brief history of the <strong>RHS</strong> <strong>Lily</strong> Committee<br />

by Brent Elliott . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28-35<br />

A review of English language Monographs on<br />

the genus Lilium 1873-2006<br />

by Cameron Carmichael. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35-46<br />

Chris North<br />

by Alan Mitchell . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47-52<br />

A celebration of Branklyn Garden<br />

by Steve McNamara. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53-55<br />

Dr A.F. Hayward (1933-2006)<br />

by Richard Dadd . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56-57<br />

Growing lilies in Switzerland<br />

by Pontus Wallstén . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58-67

Contents<br />

Alisdair Aird<br />

by Harris Howland . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68-69<br />

On the road in search of lilies<br />

by Alan Mitchell . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70-79<br />

Erythronium<br />

by Brian Mathew . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80-86<br />

Trumpet lilies<br />

by Walter Erhardt . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87-90<br />

A lilium delight – Downunder<br />

by Charles and Lee Reynolds . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91-97<br />

The lilies of Gilbert White<br />

by Jeff Coe . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98-103<br />

Liliaceous plants in the Nizhnekhopersky<br />

Nature Park, Russia<br />

by Vjacheslav Byalt and Gennady Firsov . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104-122<br />

The International <strong>Lily</strong> Registrar<br />

by Kate Donald . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123-124<br />

★ ★ ★<br />

About the <strong>RHS</strong> <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 126<br />

Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127-129<br />

Picture credits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129<br />

Guidelines for authors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 130

NOTES ON AUTHORS<br />

Katsuro Arakawa has been working at the headquarters of Sapporo Foundation for<br />

Greener Parks since 2006. He was the director of Yurigahara Park in Japan where he<br />

created the World <strong>Lily</strong> Gardens 1987-2005, founder member of the <strong>Lily</strong> Society in Japan<br />

and is a major contributor to the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> seed distribution. He was awarded the Lyttel<br />

Cup in 1998.<br />

Vjacheslav Byalt, PhD, is a Senior Research Associate in the department of Vascular Plants<br />

in the Herbarium of the Komarov Botanical Institute of the Russian Academy of Science.<br />

His main interests are plants of the family Crassulaceae and the flora of protected territories<br />

including the flora of the Khoper River and of the steppe zone of Russia.<br />

Cameron Carmichael is a retired professional horticulturist who gardens in 2 acres<br />

in central Scotland where he grows 3,500 different taxa including 100 lilies. He has a<br />

particular interest in garden plant conservation including old cultivars and is a member of<br />

the Plant Conservation Committee of the NCCPG.<br />

Roy Carter was friends with Derek Fox for nearly 40 years through their common interest<br />

in rhododendrons and camellias. He was Derek’s deputy chairman for the Essex <strong>Group</strong><br />

of the NCCPG and succeeded him as Chairman in 1992. He took over coordinating the<br />

projected dispersed collections of Division 2 lilies (Lilium martagon and hybrids) and<br />

erythroniums when Derek became ill and has been a member of the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> for just<br />

over ten years.<br />

Jeff Coe runs his own company working in asset and corporate finance specialising in IT<br />

and is a freelance web designer and was a professional athlete. Jeff was the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong><br />

Newsletter Editor from 2003 until 2006 and is currently the <strong>Group</strong>’s Web Producer. He<br />

gardens in Hampshire by the sea just 20 miles south of Selborne.<br />

Richard Dadd has been a member of the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> for over 40 years, and served on the<br />

Committee for 15 years of them, working closely with both the then Chairman, Dee Martyn<br />

Simmons and Editor of both the newsletter and yearbook, Tony Hayward. He is interested<br />

in a wide range of plants especially lilies and alliums.<br />

Kate Donald trained in horticulture at Wisley and the Royal Botanical Garden, Edinburgh.<br />

She was International Daffodil Registrar and Assistant Editor at the <strong>RHS</strong> and has recently<br />

been appointed International <strong>Lily</strong> Registrar. She is also an authority on pre 1930 daffodil<br />

cultivars and crofts on the west coast of Scotland.<br />

Brent Elliott, PhD, is the <strong>RHS</strong> Society’s Historian, having been Lindley Librarian for over<br />

25 years.<br />

Walter Erhardt is a teacher and horticultural author. He lives in Bavaria, Germany, and<br />

has for many years been interested in lilies and daylilies. He has written books about the<br />

genera Hemerocallis and Narcissus, but his most important works are The European Plant<br />

Finder and ZANDER- Dictionary of Plant Names.<br />

1

Gennady Firsov, PhD, is Senior Research Associate and curator of the arboretum and nursery<br />

at the botanic garden of the Komarov Botanical Institute. Born in stanitsa Kumilzhenskaya<br />

in the Volgograd region, he took part in the investigation of the flora of the area, and made<br />

recommendations for the creation of the Lower Choper Nature Park in 2003. He is a member<br />

of the IDS, of the British Conifer Society and of the Russian Botanical Society.<br />

Harris Howland has been interested in lilies for over 40 years and now maintains a<br />

relatively good collection of lilies and fritillaries. He has served on two occasions as<br />

chairman of the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> and collaborated on the Gardeners’ Guide to Growing Lilies.<br />

Pat Huff, PhD, is Chairman of the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong>. An American living in Britain, she has<br />

responded enthusiastically to the horticultural opportunities presented by her adopted<br />

country. She gardens in Cambridgeshire and has special interests in species peonies and<br />

caudiciform succulents as well as lilies and fritillaries. She is Editor of Plant Heritage, the<br />

bulletin of the NCCPG, the Garden History Society News, and the Fritillaria <strong>Group</strong> Journal.<br />

Steve McNamara originally trained as an engineer, but after a long spell in hospital started to<br />

work in the London Parks Department and re-trained in horticulture starting with a City and<br />

Guilds in Amenity Horticulture and then at Kew. After living in Canada for 18 years he moved<br />

back to Britain to be Property Manager and Head Gardener at Branklyn near Perth where are<br />

held several National Collections including the Mylnefield <strong>Lily</strong> Collection.<br />

Brian Mathew, VMH was for 25 years, a taxonomic botanist in the Herbarium at the Royal<br />

Botanic Gardens, Kew, specialising in the petaloid monocotyledons. He is the author of<br />

many books on garden plants, in particular bulbous genera.<br />

Alan Mitchell is an optimistic amateur gardener with a passion for growing lilies who lives<br />

in Scotland. He finds their difficulty a challenge and their diversity and beauty endlessly<br />

engaging and therapeutic.<br />

Gian Lupo Osti is an Italian dendrologist and past President of the International<br />

Dendrology Society. He gardens in Northern Lazio on the hills overlooking Lake Bolsena;<br />

he is particularly interested in peonies.<br />

Charles and Lee Reynolds both served in the Australian Army. Lee joined the Education<br />

Corps and when she left became a Business Manager and Consultant. Charles has a degree<br />

in cello performance and after playing in the Western Australia Symphony Orchestra joined<br />

the Army as an Artillery Officer serving on several occasions overseas. He is now in the<br />

Reserves, and responsible for the entertainment taken to Australian forces overseas.<br />

Arne Strid is Director of the Göteborg Botanical Garden and has a particular interest in the<br />

flora of Greece and author of several books on the subject.<br />

Pontus Wallstén, is a student at the University of Westminster in London, where he studies<br />

Film and TV production. When he is not behind a camera, he can be found in his parents’<br />

garden in Switzerland, taking care of his collections of rare plants from all around the<br />

world. The highlight of these collections are the lilies, which Pontus spends a lot of time<br />

photographing thereby combining his two main hobbies.<br />

2

From the Chairman<br />

Pat Huff writes an introduction to the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> and<br />

its history in recent years.<br />

“Amateurs determined to grow even the<br />

apparently ungrowable” is the way Brent Elliott<br />

describes the membership of the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong>.<br />

His fascinating article (see pages 28-35)<br />

chronicles the <strong>Group</strong>’s inception in 1932 and<br />

its activities up until 1990, the beginning of the<br />

end of the twentieth century. Although there<br />

have been some fundamental changes over the<br />

<strong>Group</strong>’s 75 year history, Brent’s characterisation<br />

of our members is as true now as it ever was.<br />

Despite the presence of many professional<br />

gardeners and nurserymen amongst us, we are<br />

still all “amateurs” in the original sense: lovers of these beautiful, demanding and<br />

often exasperating plants.<br />

Taking up the history of the <strong>Group</strong> where Brent left off, Harris Howland was<br />

succeeded as Chairman of the <strong>Group</strong> by Tim Whiteley. Tim’s woodland garden<br />

on the Bucks/Northants border is one of the best places in England to see lilies.<br />

(And snowdrops. And woody plants, particularly the genus Euonymus.) His<br />

encyclopaedic knowledge of the genus combined with his experience as an<br />

<strong>RHS</strong> judge and his international contacts throughout the lily world ensured that<br />

the <strong>Group</strong> was always in touch with the latest developments in breeding and<br />

cultivation.<br />

Tim was Chairman when I joined the Committee in 1998. Although the<br />

founding members of the <strong>Lily</strong> Committee back in 1931 included such illustrious<br />

names as Frederick Stern, Arthur Grove and Amos Perry, at my first meeting I was<br />

in the company of the likes of Tim Whiteley, Harris Howland, Michael Upward<br />

and the late Derek Fox (see pp. 15-17). When I met him Derek had already<br />

published the indispensable Growing Lilies, and created the wonderful Bullwood<br />

hybrids such as ‘Lake Tahoe’ and ‘Lake Tulare’. These lovely lilies are now sadly<br />

rare in cultivation but incredibly sought after when they turn up in the trade or<br />

in the <strong>Group</strong>’s bulb auctions. Despite his immense prestige, Derek was funny,<br />

modest and very friendly to a newcomer. When I first joined the Committee, two<br />

other links to the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong>’s heroic past were also still around, and equally<br />

helpful. Dee Simmons (see pp. 5-8) and I spoke regularly on the phone, and I<br />

sat next to Bill Baker at the lunch celebrating Harris Howland’s being awarded<br />

3

the Lyttel Cup. When I mentioned that I liked fritillaries as well as lilies, he<br />

dropped his voice and whispered conspiratorially that he had always found<br />

them “drab, brown little things”. Although he was a skilled and enthusiastic lily<br />

hybridiser, Bill believed that such plants were destined to go out of cultivation<br />

sooner or later, so he only registered four of his many creations. After his death<br />

in 2001, the <strong>Group</strong> was given his lily library and collection of bulbs. Their<br />

sale led to the establishment of a Bill Baker Fund that goes to support notable<br />

achievements in the lily world.<br />

After Tim stepped down as Chairman of the Committee, Harris Howland was<br />

prevailed upon to take over once again. As well as having an expert’s eye for<br />

a good lily, Harris has a knack for strengthening the Committee. He persuaded<br />

Alisdair Aird to join, as well as nurserymen Richard Hyde and Nigel Rowland,<br />

and got Alan Hooker back again to do the seed distribution. For a number of<br />

years he and Colin Crosbie formed an irresistible double-act at the annual bulb<br />

auction. Under his leadership, the website started by Ian Boyd assumed even<br />

greater importance with Jeff Coe as webmaster.<br />

The biggest event of this period was undoubtedly the 2004 International <strong>Lily</strong><br />

Conference, masterminded by Tim Whiteley and attended by dozens of members<br />

from all over the world. After days of fascinating lectures and garden visits, the<br />

conference culminated in a lily show at Wisley and a gala dinner where John<br />

Lykkegaard was awarded the Lyttel Cup.<br />

Today the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> faces a number of challenges, some of them to its very<br />

identity. Brent reports that “in 1978 Council decided that the Committee should<br />

become semi-independent”, and we have remained that way ever since. The<br />

Society is now asking fundamental questions about how (and if) the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong><br />

fits into its larger picture. Our “semi-independent” relationship is no longer<br />

tenable, and we must redefine it. The Committee is grappling with various<br />

possible outcomes, and was helped and encouraged by the frank exchange<br />

of views that took place at the 2007 AGM in Birmingham. Along with the<br />

challenges there is a plethora of exciting opportunities. E-mail allows us to keep<br />

in touch with an ever-increasing number of our members without depending on<br />

an expensive and unreliable postal service. The internet can be mined for the<br />

most extensive and arcane information on lilies. Plant breeders keep on coming<br />

up with ravishing new hybrids while there is simultaneously much greater<br />

awareness of the importance of keeping the older ones in cultivation. In 1932<br />

Frederick Stern said in Council that “there is no doubt that there is a want among<br />

members and the public to join some body devoted to lilies and their culture,<br />

where they can air their views and hear other views on their especial subject”.<br />

Seventy-five years on, it’s still true.<br />

4

Mrs D.A. Martyn Simmons<br />

Richard Dadd writes in appreciation of our late President,<br />

Mrs D.A. Martyn Simmons, who was an inspiration and driving force<br />

within the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> for more than 30 years.<br />

RS D.A. MARTYN SIMMONS, who died at home on 17 November 2004 at the age<br />

Mof<br />

92, was one of the most outstanding lily growers in England during the<br />

second half of the last century. She joined the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Committee in 1963;<br />

was its Chairman from 1982 to 1990, and 1994 to 1995; and thereafter became<br />

President. She also served on <strong>RHS</strong> Floral Committee B (whose main remit was<br />

trees and shrubs) from 1965 to 1997. Her name will forever be associated with<br />

Quarry Wood, the large woodland garden in Burghclere where she cultivated<br />

lilies and many other plants from 1954 until her death.<br />

Mrs Simmons – Dee to all her friends – was born Daisy Adeline Halpin<br />

(her given names not always spelt thus) on 23 October 1912 in Janesboro,<br />

Co. Limerick (now in the Republic of Ireland) where her father was an engineer.<br />

She spent her childhood in Ireland where she acquired an interest in plants from<br />

her mother, but later moved with her family to the Southampton area. In 1939<br />

she married Martyn Alan Simmons, a miller and engineer.<br />

By the early 1950s Mr and Mrs Simmons were living near Newbury in Berkshire,<br />

but looking for a larger property. They found Quarry Wood, a large house and<br />

woodland garden of 15 acres, on the road to Winchester a few miles south of<br />

Newbury but just across the border in Hampshire. It had come onto the market<br />

following the sudden death of its owner, Walter Bentley, in April 1953. He had<br />

been a keen lily grower and one of the founder members of the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> in<br />

1933. When he acquired Quarry Wood in 1934 it consisted ‘largely of an expanse<br />

of unkempt, rough grass, drifts of bracken and scarcely controlled weeds. It<br />

was bounded on east, west and south by neglected woodland, overrun with<br />

brambles and tangled undergrowth.’ In 19 years Mr Bentley had transformed<br />

this wilderness and planted magnolias, rhododendrons and many other trees and<br />

shrubs to create a haven for the rare species lilies that interested him. But nature<br />

is always keen to reassert herself, and with the property standing empty and<br />

neglected for over a year, and proving difficult to sell, it was going downhill.<br />

When Mr and Mrs Simmons purchased Quarry Wood in 1954 they were<br />

comparative novices, and had not quite realized what they were taking on. These<br />

difficulties were compounded by a series of bizarre events recounted by Anthony<br />

Hayward in ‘A Garden called Quarry Wood’ (Lilies & Related Plants, 1992-1993,<br />

pp. 133-138). The only ray of sunshine at this time was the arrival of west<br />

countryman Maurice Woodgates to take up the post of gardener. The subsequent<br />

5

Dee Simmons and her husband Martyn admiring an acer in the garden at<br />

Quarry Wood.<br />

partnership of Mrs Simmons and Mr Woodgates turned out to be a winning one:<br />

the garden once more became celebrated for its lilies, and Woodgates remained<br />

at Quarry Wood for the rest of his working life.<br />

Over the years Dee transformed herself from a beginner to an acclaimed<br />

expert: so much so that in 1963 she was fêted by the North American <strong>Lily</strong> Society<br />

(NALS) when she made a coast-to-coast trip in the USA. As well as taking in the<br />

6

21st Annual Show of the Garden Club of Virginia at Ashland, and the NALS 16th<br />

Annual Show at the National Arboretum in Washington (DC), she visited many of<br />

the great names in lily growing at that time and their gardens. At the NALS show<br />

she was delighted to meet many of her correspondents – ‘a happy experience to<br />

pin faces to names’ as she put it. Some of them would later visit Quarry Wood.<br />

She ended her journey in the Californian mountains looking at rare lilies in their<br />

natural habitat. Dee recalled it as a memorable trip, full of warmth and kindness.<br />

Dee was a charming and persuasive woman, warm and effusive, affectionate<br />

to those she took to; but her outgoing nature concealed an inner strength and<br />

determination – although she did not invariably get her own way. Remarkably,<br />

during the 40 years that I knew her she always had the zest and appearance of<br />

someone ten years younger. She was an enthusiastic networker, long before<br />

that term gained general currency, and had many contacts at home and abroad<br />

– particularly in Australia, New Zealand and the USA.<br />

Dee was catapulted into the chairmanship of the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Committee in<br />

1982 during the middle of a meeting, immediately following her predecessor’s<br />

resignation. Chairing meetings was not her forte, but she proved to be adept<br />

at spotting people with suitable talents, then recruiting and motivating them<br />

to help the cause of lilies in general and the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> in particular. During<br />

her chairmanship she gathered about her a small nucleus of talented and hard<br />

working Committee members to put her ideas into effect: building up the <strong>Group</strong><br />

by offering its members an extensive programme of lectures, shows and outings,<br />

attractive publications, and an internationally renowned seed distribution<br />

scheme. There were also several one-offs such as the distribution of the North<br />

lilies in 1985, and she also devised ways of improving the financial position of<br />

the <strong>Group</strong>. At <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> functions she was always highly visible, introducing<br />

herself and welcoming members – especially new ones.<br />

Throughout most of Mr and Mrs Simmons’ time at Quarry Wood the garden<br />

was open to visiting gardening groups. From time to time it also hosted<br />

international lily conferences and the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> itself. Dee and her husband<br />

Martyn were generous hosts, and on such occasions a marquee would be erected<br />

on the spacious lawn to the south of the house where drinks and refreshments<br />

would be served. These gatherings were very popular, and guests were free to<br />

wander around the 15 acres of grounds whilst Maurice Woodgates was usually in<br />

attendance. The garden suffered terribly from the great storms of 1987 and 1990<br />

which felled many of the older trees.<br />

Dee’s later years were, inevitably, saddened by the passing of so many old<br />

friends. Her husband Martyn, who had been such a great support, died in 1999<br />

(Obituary, The Times, 21 June 1999) and Woodgates followed a few years later.<br />

Nevertheless, she continued defiantly to outface old age.<br />

7

But, now that she is gone, how should we remember her? – As a generous<br />

woman who loved lilies, loved people, and brought them together – a memory<br />

that will be cherished by those who knew her for as long as memory lasts.<br />

She is survived by her son, Anthony Martyn Simmons, and three<br />

grandchildren.<br />

Mrs Daisee Adelaine Martyn Simmons, plantswoman and lily grower<br />

Born 23 October 1912, died 17 November 2004 aged 92<br />

8<br />

★ ★ ★<br />

Colonel Iain Ferguson was Chairman of the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> from<br />

1978 until Mrs Simmons took over in 1982 and<br />

wrote the following tribute.<br />

During the 48 years that Sir Fred led the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> he gathered<br />

around him the leading and most distinguished plantsmen of the<br />

day – even The President of the <strong>RHS</strong> was on his committee. When<br />

he, and most of his colleagues had gone, the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> lost its very<br />

special position and became vulnerable. Oliver Wyatt, his successor<br />

and a friend of Dee’s, was a grower and hybridiser but no business<br />

man and no match for the <strong>RHS</strong> “money men”. When he was worn<br />

out the <strong>RHS</strong> appointed Frances Perry, a gardener and talented garden<br />

writer but too busy to have the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> at the top of her agenda,<br />

particularly at a troubled time. It was Dee who stepped centre stage<br />

and who fired us all up with her infectious enthusiasm and her<br />

determination that the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> would survive and flourish. She<br />

preferred to work from the position of Vice Chairman but there was<br />

never any doubt as to who the boss was. In 1982 she finally agreed<br />

to be Chairman which she should have done many years before. If<br />

Dee had not been there the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> would have died in the mid<br />

1970s. It is for that, and her friendship and advice, that I shall always<br />

treasure her.<br />

Additional reference:<br />

Dee Simmons by David Parsons Lilies and Related Plants 1997-1998, (pp. 88-90).

The conservation of wild lily<br />

populations in Japan<br />

For many years Katsuro Arakawa has been a major donor to the<br />

<strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong>’s seed distribution scheme. Here, he describes the<br />

conservation work he is involved with in Japan.<br />

Y FIRST CONTACT with the <strong>RHS</strong> <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> was in the winter of 1989, when<br />

MI<br />

was building the collection of live lilies at Yurigahara Park in Sapporo. I<br />

remember my excitement at the inspiring present of goodly amount of various<br />

lily seeds from the <strong>Group</strong>’s seed distribution in the spring of 1990.<br />

I owe many salutary lessons to this seed exchange – and not just that, but it<br />

has also brought me new friends in diverse corners of the world. I have had great<br />

pleasure from imagining each person’s gardening life, from the letters and emails<br />

they send me.<br />

Since spring 1996, we have organised our own domestic seed distribution,<br />

here in Japan. And our own <strong>Lily</strong> Society has now been established, grown from<br />

the initial nucleus of lily lovers brought into contact with each other through our<br />

domestic seed distribution. Some members are on the staff of botanic gardens,<br />

in charge of their lily collections. Our seed distribution helps to avoid inbreeding<br />

problems such as loss of vigour, and is a valuable fallback resource if and when<br />

strains are accidentally lost. The same of course is true of the <strong>RHS</strong> <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong>’s<br />

distribution, and seeds which we are able to supply to that distribution seem to<br />

play the same role.<br />

Our <strong>Lily</strong> Society prints The <strong>Lily</strong> Society News in spring and autumn, and organises<br />

a <strong>Lily</strong> Tour in the flowering season. We have visited the World <strong>Lily</strong> Gardens at<br />

Yurigahara Park, private lily breeders, agricultural institutes in Hokkaido, and the<br />

natural habitats of Lilium dauricum and L. japonicum. In 2006 the <strong>Lily</strong> Society<br />

held a programme of lily lectures to celebrate its fifth anniversary.<br />

We plan to hold such lectures every five years, and major topics for us will be<br />

the history of relationships between human beings and lilies, and the fragrance of<br />

lilies. It is 175 years since L. speciosum was taken back by Siebold and flowered<br />

for the first time in Europe. We have long been aware of the beauty of the<br />

lily’s form and colouring, and now find great value too in its fragrance. There<br />

is also growing interest in the importance of the fragrance to the relationship<br />

between the lily and its pollinators, and in its relevance to perfume manufacture.<br />

Fragrant lilies like L. alexandrae, L. auratum, L. japonicum, L. nobilissimum and<br />

L. rubellum are Japanese endemics. Adding L. longiflorum, six species out of 14<br />

native to Japan are fragrant.<br />

9

Lilium dauricum at Hamatonbetsu on the coast of the Okhotsk Sea in January 2005.<br />

Two lily species, L. dauricum and L. medeoloides, are present on Hokkaido,<br />

the second-largest island in the Japanese archipelago, which is where I live. Four<br />

species, L. auratum, L. japonicum, L. maculatum and L. rubellum, are endemic<br />

to Honshu, the largest island. Four other species – L. concolor, L. lancifolium,<br />

L. leichtlinii var. maximowiczii and L. medeoloides and L. speciosum – are also<br />

present or have in the past been recorded on Honshu, and L. callosum has been<br />

recorded from there, as well as from Kyushu, Shikoku and the Ryukyu Islands.<br />

Lilium concolor, L. leichtlinii var. maximowiczii, L. speciosum and L. japonicum<br />

notably the Hyuga form of L. japonicum are present on Kyushu, L. concolor,<br />

and L. leichtlinii var. maximowiczii and L. speciosum var. clivorum and some<br />

endemic L. japonicums on Shikoku. Lilium longiflorum is or was confined in<br />

the wild to the Ryukyu archipelago. Lilium alexandrae is endemic to just three<br />

islands of that archipelago, and L. nobilissimum has been limited to just one<br />

small southern island, Kuchinoshima.<br />

10

Lilium dauricum is mainly a coastal plant on Hokkaido. The bulbs establish<br />

their roots in coastal grassland or on shelves of the steep coastal cliffs. Lilium<br />

dauricum’s communities in coastal grasslands have been reduced by environmental<br />

effects, as their habitat has been altered by the installation of drainage systems for<br />

ranches, and/or by road building. Moreover, some populations are unable to selfpropagate<br />

well from seed, as the young roots of seedlings are prevented from<br />

working their way into the soil by a thick layer of grass thatch. This thatch is now<br />

thicker than in the past, as fewer horses are grazed on coastal grasslands, now<br />

that tractors are used instead. Another possible cause of decline in L. dauricum<br />

is a reduction in the number of its pollinators. It is suggested that the pollinators<br />

of L. dauricum are the largeish butterflies, Aporia crataegi (black-veined white)<br />

and Papilio machaon (swallowtail). Both eat each host plants in their caterpillar<br />

stage. Malus sieboldii (Japanese crabapple) and M. baccata var. mandshurica<br />

(a variety of Siberian crabapple) are the host plants of A. crataega; Glehnia<br />

littoralis (silvertop) is the host plant of P. machaon. In the past, good stands<br />

of these host plants were present near sites of L. dauricum. Now, however,<br />

the host plants have disappeared from some habitats. Malus sieboldii and M.<br />

baccata var. mandshurica have in some places been destroyed by controlled<br />

burning in early spring. The young shoots of G. littoralis were cleanly picked out<br />

as the ingredient of a seasonal salad. G. littoralis lived on the coast of Ishikari<br />

close to my residence, but is now absent around declining communities of the<br />

lily. Although G. littoralis still thrives bravely in the nature refuge ten kilometers<br />

away, pollinators cannot survive outside the refuge.<br />

In nature the range of L. dauricum was limited to coastlines and to some of<br />

the high mountains in Hokkaido. However, in the last 20 years this lily has been<br />

increasingly visible on roadside verges. As its distribution is expanded along<br />

roadsides in the high mountains, there is a fear that this artificial expansion of its<br />

distribution could contaminate relict communities.<br />

Villagers in most L. japonicum regions campaign actively for the protection<br />

of this lily. There are two motivations behind this. Many people are fired by<br />

nostalgia, wanting to recreate the view filled with L. japonicum in full flower,<br />

which villagers used to see as a matter of course every year in the old days. Others<br />

hope to boost their secluded mountain hamlets by attracting a lot of visitors to<br />

see a hillside full of L. japonicum in bloom. Both groups talk about how the lily<br />

has been declining. Conservation activists and the Environment Ministry allege<br />

that the decline is caused by collecting, but my own belief is that it is caused by<br />

lifestyle changes at these mountain village, and by forestry depression.<br />

Ishima, which I visited in 2004, is a small island nine and half a kilometers<br />

around, located east of Sikoku Island. Junior high school students here are<br />

absolutely committed to conserving communities of L. japonicum Ishima form.<br />

11

Above left, Lilium callosum var. flaviflorum at Yurigahara Park. The lily was<br />

collected on Okinawa Island and propagated by scaling.<br />

Above right, two different lilies share a niche together in the wild:<br />

L. callosum var. flaviflorum (right) and L. longiflorum (left).<br />

Their parents told me that the slope of island used to be turned pink by flowers<br />

of L. japonicum every early May when they were their children’s age. In those<br />

days the islanders all went up the mountain together each autumn, to clear-fell<br />

one evergreen forest plot for firewood for cooking. This worked on a 20-year<br />

rotation, taking 20 years to clear each plot in turn around the island. This system<br />

was environmentally optimum for the full life cycle of the lily, from germination<br />

to seed dispersal. But as bottled gas became common on the island the evergreen<br />

forests were neglected, bamboo thickets covered the hillsides, and L. japonicum<br />

rapidly lost its habitats.<br />

Hard-up junior high school students have still been able to collect reasonable<br />

numbers of flowering L. japonicum from the hillsides, and it’s been a tradition<br />

to sell these to the islanders, so as to help fund the school trip. This has been<br />

important for those old people who were unable to go to the hillside – they<br />

could enjoy the L. japonicum season with a vase of the flowers brought by the<br />

students. So in the hope of perpetuating L. japonicum, in gratitude for the lily’s<br />

beauty and to follow in the tradition, the island’s people now continue thinning<br />

and trimming in the dense jungle of evergreen broad-leaved forest, to promote<br />

the lily’s seeding and growth.<br />

When horses were kept as a source of power for cultivation, Miscanthus<br />

sinensis (Japanese silver grass) and Imperata cylindrica (cogon grass) growing<br />

on the slopes between the forest and the lowland fields were cleared out and<br />

used for litter, thatch and fodder. Trees and branches in the forest near human<br />

12

Top, Lilium japonicum Ishima form from the mountain slope of Ishima Island.<br />

Above left, L. nobilissimum in cultivation at Yurigahara Park.<br />

Above right, L. japonicum var. platyfolium seen in the wild at Tottori Hanakairo Park.<br />

settlements were regularly cut for the fuel. Now the grass is no longer cleared out<br />

of the grassland, as tractors need no litter or fodder; and the forest is untrimmed,<br />

now that rice is boiled on bottled gas cookers. So the areas of grassland and<br />

forest become darker and darker, impeding the growth of lilies and reducing<br />

their populations.<br />

Some lily populations have been reduced by plant collecting: L. japonicum<br />

13

var. abeanum is a case in point, or perhaps L. japonicum Hyuga form. Other<br />

lily communities have certainly been destroyed by developments such as dam<br />

construction, road building and estate development. However, it must have been<br />

often the case that habitats are dying through environmental changes such as<br />

those which result from failure to trim grassland and forestry in the old ways. It<br />

can be said that L. auratum, L. callosum, L. japonicum and L. rubellum are the<br />

species whose existence in Japan has been influenced most by human lives.<br />

The Okinawa population of Lilium callosum (a population known from its<br />

yellow flowers as var. flaviflorum) was rediscovered for the first time in these<br />

20 years. Yet it has already fallen victim to changing times, with changes in its<br />

habitat management. The island is in “Typhoon alley”, and the thatch which has<br />

been traditional for roofing material there has now given way to concrete. So<br />

grassland has been neglected, allowing over-abundant growth of Japanese silver<br />

grass over two metres in height, destroying almost all the lily’s habitats. On a visit<br />

last year we found just one population of 50 plants, where Imperata cylindrica<br />

grassland had been artificially weakened. As far as I know there is only one other<br />

population on the island now.<br />

Lilium nobilissimum was endemic to Kuchinoshima island, Kagoshima<br />

Prefecture, where its habitat was restricted to the ocean cliff. Lilium nobilissimum’s<br />

Japanese name is Tamoto-yuri: Tamoto is the pouch-forming sleeve of Japanese<br />

clothing, and in the past men lowered on a bamboo contraption slung from the<br />

cliff-top to gathered the bulbs of the lily kept them in this pouch. This precarious<br />

undertaking seems to have been all too successful: the lily is said to be extinct<br />

in the wild now. A few cultivated plants preserve the species. However, in our<br />

Yurigahara Park collection this lily’s germination rate has now declined to about<br />

20%, which I think must be caused by inbreeding depression. Although we will<br />

outbreed the strain with another strain next summer, I am not very hopeful for<br />

the future, over the next several generations. [Editor’s note: This lily is also in<br />

cultivation in the UK, and perhaps elsewhere, but from seed kindly donated<br />

to the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> distribution by Mr Arakawa in the past, so these plants are<br />

unlikely to help with the inbreeding problem.]<br />

Lilium alexandrae ranges over three islands of this same southern chain.<br />

Though it has been reduced by collection, it is sustained in the wild by the<br />

islander’s keen conservation work.<br />

The only surviving habitats of L. concolor are now confined to Shikoku Island,<br />

and the wild population declines.<br />

Lilium longiflorum, L. leichtlinii var. maximowiczii, L. speciosum, L. maculatum<br />

and L. medeoloides are common lilies in their original habitats, through exemplary<br />

preservation and conservation – a textbook case.<br />

14

Derek B. Fox 1926 – 2007<br />

Roy Carter writes in tribute to one of the outstanding lily breeders<br />

of last century, Editor of the Bulletin (1981 & 1982) and key member<br />

for many years of the <strong>Lily</strong> Committee.<br />

EREK WAS BORN in Thorpe Bay, Essex in April 1926 and at an early age showed<br />

Da<br />

keen interest in nature, an interest which was to remain with him all<br />

his life. In 1957 Derek and his wife Elizabeth (Betty), purchased a one acre<br />

overgrown plot on the edge of Hockley Woods just a few miles from where he<br />

was born. Here Derek and Betty created a woodland garden which, over the<br />

years came to be enjoyed by their many visitors. Being an acid soil the first<br />

choice of plants were those of the Ericaceae and he assembled collections of<br />

camellia, magnolia and rhododendron species and hybrids which, together with<br />

many exotic trees formed the structure which was to become home of the many<br />

plants of the Liliaceae family he grew.<br />

Derek was particularly successful, despite the low Essex rainfall, in growing<br />

some of the large leaved rhododendrons such as Rhododendron eximeum, R.<br />

macabeanum and R. grande. Over the years he made many rhododendron and<br />

camellia crosses, the result of one such camellia cross being named ‘Betty Fox’<br />

after his wife.<br />

However, Derek’s main love were his lilies. In the early to mid 1960s he began<br />

a hybridising programme using lily species found growing on the west coast of<br />

the United States of America resulting in the creation of the Bullwood Hybrids.<br />

His many creations such as ‘Lake Tulare’, ‘Lake Tahoe’ and ‘Coachella’ to name<br />

but a few, are still prized and sought after today, although rare in cultivation.<br />

15

Two of Derek Fox’s lily cultivars: above ‘Lake Tahoe’ and below, ‘Lake Tulare’.<br />

Recently members of the <strong>RHS</strong> <strong>Lily</strong><br />

<strong>Group</strong> instigated a conservation project<br />

to save these magnificent plants.<br />

Derek was a person very much<br />

involved at all levels in promoting the<br />

growing of lilies, being a former editor<br />

of the <strong>Lily</strong> Year Books and a regular<br />

contributor to both them and to those<br />

of the North American <strong>Lily</strong> Society. He<br />

also authored the <strong>RHS</strong> Wisley Handbook<br />

on lilies and in 1985 his monograph<br />

Growing lilies was published – a work<br />

still relevant today and sought after by<br />

would be lily growers.<br />

He served for many years on the<br />

<strong>RHS</strong> <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> committee and was<br />

awarded the <strong>Lily</strong> Cup; also the Lyttel Cup for his work in connection with the<br />

genus. In 2002 he was honoured by the North American <strong>Lily</strong> Society by being<br />

awarded the E.H. Wilson medal. The citation read: ‘In recognition of his life-long<br />

devotion to lilies’.<br />

Derek was also a founder member of the National Council for the Conservation<br />

of Plants and Gardens (NCCPG) Essex <strong>Group</strong> and became its first Chairman on<br />

16

Two more Bullwood Hybrids: above, ‘Coachella’ and below, ‘Rosewood’.<br />

its inauguration in 1980, a position he<br />

held until his retirement from office in<br />

1992. His guidance and commitment<br />

to the Essex <strong>Group</strong> continued by<br />

promoting and supporting the aims of<br />

the charity, and also by opening his<br />

garden through the National Gardens<br />

Scheme. He was instrumental in<br />

proposing that the Essex <strong>Group</strong> hold<br />

dispersed National Collections of<br />

Lilium martagon and its Division II<br />

hybrids and that of Erythronium – a<br />

work still in progress.<br />

He travelled widely in Europe,<br />

North America, the Baikal region of<br />

Central Asia and Nepal. Always, where<br />

possible, collecting plants or seeds which he generously distributed amongst his<br />

friends around the world. Derek had a great love of all plants and was a great<br />

plantsman. Derek will be missed by all who knew him for his generosity in gifts<br />

of plants and seeds, his willingness to offer help and share his knowledge with<br />

others, for his ready smile and great sense of humour, but the legacy of his plant<br />

creations will, hopefully, live on.<br />

17

18<br />

The lilies of Greece<br />

Arne Strid writes about the five species endemic to this ancient land.<br />

HE GENUS LILIUM is represented by five species within the borders of present-<br />

Tday<br />

Greece, but probably only two of them were known in antiquity. The<br />

famous “lilies” of Minoan wall paintings in Crete and Santorin (Thira) are not lilies<br />

as currently understood, but represent the sea daffodil, Pancratium maritimum<br />

(Amaryllidaceae), a species of sandy beaches still widespread throughout Greece<br />

although declining through development of tourist facilities.<br />

Plant names used by Theophrastos (c. 370-285 B.C.) are often difficult to<br />

interpret, but it seems fairly certain that κρι´νον (krinon) refers to the white<br />

Madonna <strong>Lily</strong> (Lilium candidum). Κρι´νον το πορφυρου´ν (krinon to porfiroun)<br />

may refer to the scarlet Lilium chalcedonicum which occurs in mountains of<br />

the Peloponnese and Sterea Ellas, including Parnes or Parnitha near Athens,<br />

and may well have been known to Theophrastos. Ημεροκαλλζς (imerokalles)<br />

has been interpreted as Lilium martagon but this seems more doubtful both<br />

for etymological reasons and for the fact that the latter occurs mainly in the<br />

northern parts of modern Greece, reaching its southern limit in Parnassos and<br />

other mountains of central Sterea Ellas.<br />

Modern botanical exploration of Greece started with John Sibthorp (1758-<br />

1796) who on his grand tour in 1786-1787 and on a subsequent tour in 1794<br />

gathered the material for the magnificent Flora Graeca, which appeared in ten<br />

folio volumes in 1806-1840, i.e., long after the death of Sibthorp. Flora Graeca<br />

contains 966 hand-coloured copper engravings based on drawings made in the<br />

field by the artist Ferdinand Bauer who had travelled with Sibthorp – alas, not a<br />

single lily.<br />

Flora Graeca was preceded by an octavo work without illustrations, the Florae<br />

Graecae Prodromus (1806-1816), which amounts to a comprehensive Flora of the<br />

areas visited by Sibthorp, i.e. southern parts of present-day Greece and coastal<br />

regions of western Anatolia as well as Cyprus. Three lilies are mentioned in<br />

the Prodromus, viz. Lilium candidum, L. chalcedonicum and L. martagon. All<br />

three had been known to Linnaeus who in Species Plantarum (1753) cited them<br />

from “Palaestina, Syria”, from “Persia” [probably in error], and from “Hungaria,<br />

Helvetia, Sibiria, Lipsiae”, respectively.<br />

In the Prodromus geographical information for Lilium candidum reads: “In<br />

Tempis Thessaliae. D. Hawkins. In hortis Graeciae frequens. Sibth.”. Apparently,<br />

John Hawkins, another wealthy English gentleman who had travelled in Greece<br />

partly together with Sibthorp and partly on his own, had observed this species<br />

growing in the Tembi valley in Thessaly (just south of Mount Olympus) whereas

Sibthorp knew it only from cultivation. Hawkins made several other remarkable<br />

discoveries. For instance, he was the first to observe the horse chestnut, Aesculus<br />

hippocastanum, growing wild in the same general area. At that time it was already<br />

known in cultivation in central Europe, having presumably been introduced via<br />

Istanbul, but its native distribution is restricted to a rather small area in Greece<br />

and southern Albania. Lilium chalcedonicum was reported from “montis Parnassi<br />

sylvosis, et in insulâ Zacyntho” (the latter certainly in error), whereas L. martagon<br />

was said to grow “in montosis umbrosis Graeciae” without further specification.<br />

In Conspectus Florae Graecae (1904) – still the latest comprehensive Flora<br />

of Greece – Eugen von Halácsy listed Lilium chalcedonicum and L. martagon<br />

from several localities in the mountains of Sterea Ellas and Thessaly, and a new<br />

species, L. heldreichii, was added. The latter had been described by Freyn in 1880<br />

from Mt Parnitha (Parnes) in Attica and was said to differ from L. chalcedonicum<br />

in the broader leaves and 1-flowered stem. As we shall see, however, the latter<br />

shows considerable variation according to the habitat and it is almost certain the<br />

L. heldreichii is nothing but a depauperate form of L. chalcedonicum. The white<br />

madonna lily, Lilium candidum, was reported “in rupestribus regionis montanae”<br />

as well as “frequenter colitur quoque in hortis”, indicating that it grows wild<br />

in the mountains and is also frequently cultivated. Finally, an interesting new<br />

species was added: Lilium albanicum, collected on Mount Smolikas in Epirus by<br />

the Italian botanist Antonio Baldacci. This species had been described already by<br />

August Grisebach in 1846, based on his own collection in 1839 from Scardus or<br />

Šar Planina, a large mountain range on the present border between Macedonia<br />

and Kosovo. It is a relatively small, early-flowering species with deep yellow<br />

flowers, growing in meadows at high altitude on non-calcareous substrate.<br />

A distinct new species, Lilium rhodopeum, was described as late as 1952 by<br />

the Bulgarian botanist Dimiter Delipavlov. It was reported from the Bulgarian<br />

side of the Rodhopi mountains and has subsequently been found also south of<br />

the border, growing in damp meadows at an altitude of 1300-1800m. It has a very<br />

restricted distribution and in rarely seen in cultivation.<br />

The five Greek species can be keyed out as follows:<br />

1. Lower and middle leaves in whorls of 5-10.<br />

Buds more of less lanate to villous . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3. L. martagon<br />

– All leaves alternate. Buds glabrous or puberulent . . . . . . . . . . . . 2.<br />

2. Flowers yellow . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.<br />

– Flowers white or scarlet. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.<br />

key continued overleaf<br />

19

The five lilies of Greece. A: Lilium albanicum, B: L. candidum, C: L. martagon,<br />

D: L. chalcedonicum, E: L. rhodopeum.<br />

20<br />

3. Perianth segments 8-12 cm, moderately recurved<br />

from a slender base, lemon yellow . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5. L. rhodopeum<br />

– Perianth segments 3-4 cm, strongly recoiled,<br />

deep yellow. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1. L. albanicum<br />

4. Perianth segments white, only slightly recurved.<br />

Inflorescence raceme-like. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2. L. candidum<br />

– Perianth segments scarlet, distinctly recurved.<br />

Inflorescence umbel-like or flower solitary . . . . .4. L. chalcedonicum<br />

1. Lilium albanicum<br />

This is a member of the L. carniolicum complex, and is sometimes regarded<br />

as a subspecies or variety of the latter. Taken in a wide sense L. carniolicum<br />

extends from the SE Alps through mountains of the Balkan Peninsula southwards<br />

to the Pindos, with closely related taxa in NE Anatolia and the Caucasus. Greek<br />

Photos not to scale

material is relatively uniform and matches<br />

L. albanicum, which is also found in<br />

Albania, Macedonia and Kosovo. Closely<br />

related taxa, often treated as subspecies<br />

of L. carniolicum, occur elsewhere in<br />

the Balkan Peninsula. L. carniolicum<br />

subsp. jankae has recently been reported<br />

from Mt Voras (Kajmakč alan), but a photo<br />

accompanying the report (in the Greek<br />

journal Fisis 109: 20, 2005) clearly shows<br />

a rich-flowered form of L. albanicum. The<br />

latter had in fact been collected on Mt<br />

Voras (probably just north of the present<br />

border) already in 1893 by the Austrian<br />

botanist Ignatz Dörfler. Lilium jankae<br />

(L. carniolicum subsp. jankae) is a more<br />

robust plant with larger and somewhat paler<br />

flowers, occurring, e.g., on Mount Vitosha<br />

near Sofia. Plants from the Greek side of<br />

Mt Belles (the two dots in the north-eastern<br />

Lilium albanicum on Mt Gramos,<br />

alpine grassland over schist near the<br />

war memorial above Aetomilitsa,<br />

28 June, 2004.<br />

part of the map see pp. 25) are somewhat intermediate between L. albanicum and<br />

L. jankae, but closer to the former.<br />

Characteristic features of L. albanicum are the relatively small size (25-40 cm<br />

tall), 2-4 or occasionally up to 9 deep yellow flowers only 3-4 cm wide, with<br />

distinctly recoiled, deep yellow, unspotted tepals. It grows in damp meadows<br />

on non-calcareous substrates (serpentine, schist or granite) at high altitudes,<br />

generally 1600-2100 m, and flowers relatively early, from mid-June to mid-July.<br />

In cultivation in southern Scandinavia it flowers in the end of May and beginning<br />

of June. It is relatively easy to establish but seems difficult to keep for any length<br />

of time, being susceptible to diseases.<br />

2. Lilium candidum<br />

The well known white lily or Madonna <strong>Lily</strong> has been cultivated in the eastern<br />

Mediterranean area since antiquity. In Christianity it became a symbol of purity<br />

associated with the Virgin Mary, it was widely grown in monasteries and is a<br />

common motif in religious art. In addition to its ornamental and symbolic value<br />

it had reputed cosmetic and medicinal properties. From Britain it is mentioned<br />

as early as the seventh century A.D., and it features in the plays of Shakespeare,<br />

apparently being a well known plant at that time. It is hardy as far north as<br />

southern Scandinavia.<br />

21

The natural distribution of Lilium candidum is probably Greece (maybe<br />

extending somewhat further north in the Balkan Peninsula), SW and S Anatolia,<br />

Syria, Lebanon and Palestine (see pp. 25). It is found in macchie, phrygana and<br />

on rock ledges, often on limestone and generally at altitudes of 100-1200m,<br />

flowering in May and early June.<br />

For several reports of Lilium candidum it is difficult to assess whether they<br />

refer to native or naturalised plants. It is not unusual to see the species in the<br />

outskirts of villages where it clearly subsists from former cultivation, but there<br />

are also populations that appear to be wild. I have seen it on rock ledges rather<br />

far from habitations, e.g., NW of the village of Driopi in NE Peloponnese and on<br />

Mt Orliakas in northern Pindos. A large population grows in phrygana by Pirgos<br />

Dirou in the Mani Peninsula (S Peloponnese), and there are also reports from<br />

Monemvassia and Mt Arachneo. In north central and north western Greece there<br />

appear to be native populations at least on Mt Vourinos, near Konitsa and near<br />

Kastoria. Native status on the Aegean islands is more doubtful.<br />

Lilium candidum is easily recognised on the large, snow-white flowers which<br />

are generally borne 5-9 in a short raceme. The tepals are only slightly recurved.<br />

Sfikas (Fisis 42: 31, 1988) has pointed out that cultivated Greek plants tend<br />

to be taller and stouter than the wild ones with basal leaves appearing in the<br />

autumn rather than in the spring. With such a long history of cultivation there<br />

has undoubtedly been some selection, and a detailed study of variation in Greece<br />

and elsewhere in the presumably native area would be of interest.<br />

3. Lilium martagon<br />

It cannot be established with certainty whether the Martagon <strong>Lily</strong> was known to<br />

the ancient authors. In his book Paradisus Terrestris (1629) the London apothecary<br />

John Parkinson undoubtedly refers to Lilium martagon when speaking about<br />

“those kindes of Lillies, which carry diuers circles of greene leaues set together<br />

at certaine distances, round about the stalke”. In Germany where the species<br />

is native it was mentioned by Leonhart Fuchs (1542) and possibly earlier. In<br />

Denmark and southern Sweden it is known in cultivation at least since the late<br />

seventeeth century, having probably been introduced from central European<br />

stock and now naturalised, sometimes in large quantity, in old parks around<br />

mansion houses. In modern times it has become a well known garden plant with<br />

several commercial varieties.<br />

In Greece the distribution of Lilium martagon follows the mountains<br />

southwards to Parnassos in Sterea Ellas (see pp. 24). This is part of a large total<br />

range extending from Spain and France to western Siberia. In Greece it is a<br />

species of somewhat damp, semi-shaded places in deciduous woods, bracken<br />

thickets and meadows, generally between 700 and 1800 m, flowering from mid-<br />

22

June to the end of July.<br />

Lilium martagon is easily recognised by the whorled lower and middle leaves<br />

and the rather numerous flowers borne in an extended raceme. Plants from<br />

central Europe have pale, usually spotted flowers and glabrous buds. Many of<br />

the Greek plants have rather dark flowers which are either uniformly brownishpurple<br />

or have indistinct raised spots; the flower buds are lanate, i.e., have<br />

long soft woolly hairs. Such plants have been called var. cattaniae or var.<br />

sanguineo-purpureum, but it is not clear whether all Greek plants share these<br />

features. Observations on variation in and between the Greek populations would<br />

be welcome.<br />

4. Lilium chalcedonicum<br />

The native distribution of this bright scarlet lily is probably restricted to Greece<br />

and S Albania, although species with a similar flower colour occur elsewhere, e.g.<br />

L. pomponium in the Maritime Alps (see pp. 24). Being a spectacular species it was<br />

taken into cultivation early, and pictures undoubtedly showing L. chalcedonicum<br />

appear in German Kräuterbücher from the sixteenth and seventeenth century; it<br />

is likely to have come to central Europe via Turkey.<br />

Lilium chalcedonicum occurs in somewhat damp, semi-shaded, rocky places<br />

in open deciduous woods, Buxus scrub and meadows, generally between<br />

600 and 1700 m and usually on limestone. It is rarely found in large quantity<br />

except maybe on Mt Iti in Sterea Ellas where I have observed large and healthy<br />

populations. It flowers late, generally from mid-July to mid-August. The tepals are<br />

generally bright and uniformly scarlet and strongly recurved with long papillae<br />

towards the base; also the anthers are bright scarlet. Slightly paler forms with<br />

indistinct spots are found occasionally.<br />

Some authors including Halácsy (Conspectus Florae Graecae) and Hayek<br />

(Prodromus Florae Peninsulae Balcanicae) have regarded Lilium heldreichii as<br />

specifically distinct from L. chalcedonicum, differing in the consistently 1-flowered<br />

stem, lower leaves less crowded and wider, and leaves abruptly decreasing in<br />

size up the stem. Differences have also been cited in shape of bulb scales and<br />

stigma. Turrill (<strong>Lily</strong> Year Book 17: 34-36, 1954) examined fairly abundant material<br />

and came to the conclusion that there are no consistent differences. Having<br />

studied plants both in the field and in cultivation I fully agree with this view.<br />

In nature L. chalcedonicum is generally 35-70 cm tall and has 1-3 or occasionally<br />

up to 4 flowers. Transplanted into good garden soil and grown in semi-shade<br />

they may be around 100 cm tall and develop up to 12 flowers. Three bulbs<br />

were transplanted from a population on Mt Olympus in 1975 to the Copenhagen<br />

Botanical Garden and subsequently to my private garden north of Copenhagen<br />

where they were grown successfully for 25 years. The bulbs could be divided<br />

23

Right, Lilium chalcedonicum,<br />

individual with 10 flowers<br />

grown in the author’s private<br />

garden in Denmark, originally<br />

from Mt Olympus.<br />

1st August, 1980.<br />

every three years, and hundreds<br />

of plants are now in cultivation<br />

from this introduction. They<br />

are fully hardy and cultivation<br />

is not difficult although it may<br />

be necessary to watch out for lily beetles. Peak flowering is usually around<br />

1 August, and because of the late flowering seeds are not always produced.<br />

5. Lilium rhodopeum<br />

This is the rarest and least known of the Greek lilies. It was first discovered in 1951<br />

in the Rodhopi mountains of southern Bulgaria and described in the following<br />

year. It has subsequently been found in a few more localities in this area as well<br />

as south of the border, growing in secondary pastures in clearings of coniferous<br />

or beech forest at altitudes between 1200 and 1800 m (see pp.25). It is a stout<br />

plant, 40-90 cm tall, appearing from a large bulb with plump whitish scales. The<br />

stem is covered with scattered lanceolate leaves almost up to the flowers. The<br />

latter are conspicuously large (8-14 cm in diameter) with a long slender base and<br />

Lilium Distribution martagon of<br />

Distribution of<br />

Lilium chalcedonicum<br />

Lilium martagon<br />

Lilium chalcedonicum<br />

24

Distribution of Lilium candidum<br />

as currently registered in the Flora<br />

Hellenica Database. Most records<br />

refer to plants naturalised near<br />

villages, but some of the mountain<br />

populations appear to be native.<br />

Lilium albanicum Distribution of<br />

(L. carniolicum Lilium albanicum subsp. albanicum)<br />

(L. carniolicum subsp. albanicum)<br />

Distribution of<br />

Lilium rhodopeum<br />

Lilium rhodopeum<br />

25

gracefully curved, bright lemon yellow, unspotted tepals without papillae. The<br />

stamens may vary from brownish-orange to bright red.<br />

Even the largest populations of this species comprise only a few hundred<br />

individuals. There seems to be some natural variation in the number of flowers,<br />

some populations usually being 1-flowered and others regularly having 3-5 or even<br />

up to 7 flowers. The species is somewhat similar to L. jankae, but not likely to be<br />

closely related. The closest relative is rather L. monadelphum from the Caucasus.<br />

Lilium rhodopeum is rare in cultivation and appears to be difficult, although I<br />

have seen it grown successfully and in considerable quantity by a forest station<br />

in the Greek part of the Rodhopi mountains. Two bulbs transplanted in 1981 to<br />

my private garden north of Copenhagen were grown for several years; one of<br />

them regularly produced a single flower per year but did not divide, whereas<br />

the other mostly produced only a vegetative stem. They have subsequently<br />

been propagated from bulb scales and plants have been established both in<br />

Copenhagen and in the Göteborg Botanical Garden. Cross pollination has<br />

recently resulted in development of a few capsules and we hope to be able to<br />

distribute seeds to other growers, thus securing the survival of this spectacular<br />

species in cultivation.<br />

★ ★ ★<br />

26<br />

Sir Peter Smithers 1913-2006<br />

In 2001 Sir Peter Smithers was awarded the Lyttel Cup and<br />

Jim Gardiner wrote in Lilies and Related Plants of his contribution to<br />

horticulture and the world of lilies. Sir Peter introduced two exceptional<br />

lily cultivars ‘Vico Queen’ and ‘Arthur Grove’ and described them<br />

himself in the 1997-1998 yearbook. Here, Gian Lupo Osti writes a<br />

personal tribute to this great man.<br />

IR PETER SMITHERS DIED SERENELY on 8 June 2006 at the age of 92, at his house,<br />

SVico<br />

Morcote on Lake Lugano. It was a bright early summer day.<br />

In Sir Peter’s book The Adventures of a Gardener, making reference to Joseph<br />

Addison1 , he wrote “it would be nice to end life surrounded by the beauty which<br />

is my garden …….As long as memory lasts my garden will remain with me,<br />

like my own past life, a delightful dream which once I dreamed here on this<br />

mountainside.” So this wish is how it happened.<br />

Sir Peter’s life was always varied and throughout it he had a grandstand<br />

1 Joseph Addison was the essayist and poet, who died in June 1719, on whom Sir Peter<br />

published a life, for which he was awarded a DPhil by Oxford University.

view of the world’s events.<br />

During World War 2, he was<br />

in naval intelligence, alongside<br />

Commander Ian Fleming, later<br />

author of the James Bond series,<br />

where he helped provide the<br />

model for 007. This justifies<br />

the witticism that was current<br />

between his friends, “but are you<br />

more greenfinger or Goldfinger? ”<br />

After naval intelligence he<br />

was diplomat, Tory MP, Under<br />

Secretary of State, and, lastly,<br />

Secretary General of the Council<br />

of Europe. He was a passionate<br />

European along the lines<br />

expressed by Winston Churchill,<br />

but his opinions clashed with<br />

those of Anthony Eden.<br />

He found comfort away from<br />

his political life in gardening.<br />

Sir Peter and Lady Smithers<br />

at Vico Morcote in October 2001<br />

A keen interest in plants and gardens was always a constant in his life since<br />

his school days. Everywhere he went, in Washington, Mexico, Winchester,<br />

Strasbourg, and finally in Vico Morcote he gardened. In Vico Morcote he created<br />

a small eco-system of magnolias, peonies, rhododendrons, wisterias, lilies and<br />

countless magnificent plants.<br />

I met Peter for the first time, 30 years ago; I desired to know more about<br />

peonies than I could find at that time in books which were scarce and dated from<br />

the beginning of the [twentieth] century. A mutual British friend said to me “but<br />

there is Smithers who knows everything about peonies”!<br />

He became my Mentor in the world of peonies but not only that. As a gift for<br />

his 90 th birthday I translated into Italian his book The adventures of a gardener<br />

and with some friends we succeeded in publishing it: he was really enthusiastic<br />

about it.<br />

Sir Peter Smithers gardened for nearly 80 years. He made remarkable gardens<br />

in Hampshire, Mexico, Strasbourg, Lugano and West Palm Beach. He grew an<br />

impressively wide range of genera, he collected extensively and bred many new<br />

plants.<br />

I mourn a friend, a great gardener and, without rhetoric, a master of living<br />

– we say in Italy, magister vitae.<br />

27

28<br />

A brief history of the<br />

<strong>RHS</strong> <strong>Lily</strong> Committee<br />

In an article first published in Lilies and Related Plants 1992-1993<br />

Brent Elliott describes how the <strong>Lily</strong> <strong>Group</strong> came into being.<br />

(with additional material by Anthony Hayward)<br />

N 5 NOVEMBER 1931 Colonel Durham, the Secretary of the Royal Horticultural<br />

OSociety,<br />

wrote to 15 noted lily growers that “The Council of the Royal<br />

Horticultural Society has under consideration the formation of a standing<br />

committee for Lilies on the same lines as the existing Narcissus and Tulip<br />

Committee”, and invited them to a meeting on the 17th to discuss the matter.<br />

Those assembled at the meeting unanimously agreed that it was a good idea to<br />

form such a committee, and that its scope should be limited “for the present” to<br />

“Lilies, nomocharis, fritillaries and their hybrids”. The activities of the Committee<br />

were to include arranging lectures and a conference, maintaining a collection of<br />

lilies at Wisley, publishing a year-book, and compiling a register of hybrids.<br />

Who were the founding members of the <strong>Lily</strong> Committee?<br />

First and foremost, Col. F.C. (later Sir Frederick) Stern, banker, soldier and gardener<br />

of Highdown, Sussex, who appears to have been the initiator of the idea in Council<br />

and who was unanimously chosen to be the first Chairman, and in addition:<br />

Maurice Amsler, medical officer to Eton College,<br />

Roger Bevan of Crowsley Grange,<br />

J. Comber, head gardener at Nymans,<br />

John Coutts, then Deputy Curator at Kew and soon to be<br />

co-author of ‘Lilies’ 1 ,<br />

W.A. Constable of Paddock Wood nurseryman (shortly to transfer his<br />

business to Tunbridge Wells),<br />

William Cuthbertson of Dobbies’ Nurseries (elected a Vice- Chairman),<br />

Arthur Grove, complier of the Supplement of Elwes’ Monograph of the<br />

Genus Lilium (also a Vice-Chairman),<br />

Captain J.C.H. Jenkinson of Knap Hill Nurseries,<br />

Sir William Lawrence, former Treasurer of the <strong>RHS</strong>,<br />

Albert Pam of Wormleybury,<br />

1 The <strong>RHS</strong> Lindley Library possesses Fred Stoker’s review copy of Woodcock and Coutts’<br />

‘Lilies’, the title page of which Stocker annotated as follows: “nominally by H. Drysdale<br />

Woodcock KC and J. Coutts VMH….but principally by W.T. STEARN whose text I have<br />

read in great part”.

Amos Perry, the Enfield nurseryman,<br />

G.M. Taylor of Dobbies and R. W. Wallace whose bulb nursery at Tunbridge<br />

Wells was one day to amalgamate with Barr’s.<br />

The names of some additional members were chosen at that first meeting: Sir<br />

William Wright Smith of the Edinburgh Royal Botanic Garden; the plant collector<br />

W.R. Price; C.H. Curtis, editor of Gardeners’ Chronicle; Fred Stoker, future author<br />

of ‘A Book of Lilies’; R.D. Trotter the <strong>RHS</strong> Treasurer, and a number of amateur<br />

lily growers – Lt-Col. George Napier; the stockbroker Paul Rosenheim; C. R.<br />

Scrase-Dickens of Coolhurst; Mark Fenwick of Abbotswood; Andrew Harley of<br />

Glendevon; Robert James of St Nicholas; Lawrence Johnson of Hidcote and H.D.<br />

McLaren (later Lord Aberconway) of Bodnant. Council added the names of the<br />

garden designer George Dillistone and George Yeld, the York schoolmaster, who<br />

had been the first President of the Iris Society. The name of Arthur D. Cotton,<br />

who was to succeed Grove as a compiler of the Supplement to Elwes, was<br />

not mentioned at the first meeting but he was present at the second one. The<br />

Committee’s size was fixed at not more than forty.<br />

Such then was the initial membership of the <strong>RHS</strong> <strong>Lily</strong> Committee. The<br />

Committee recommended that ‘in order to widen the influence of the Committee’,<br />